What better way to distract from criminal activity than to point the finger at others?

That’s essentially the premise of a criminal case against longtime antiquities dealer and collector Georges Lotfi, which is outlined in a 36-page felony arrest warrant issued by the Department of Homeland Security and New York assistant district attorneys Taylor Holland and Matthew Bogdanos.

Lotfi provided information to investigators for years as they pursed looted antiquities and even provided a “hand-drawn” diagram of how international smuggling networks operate. It was a tip from Lotfi in 2018 that led to the seizure of the gilded coffin of Nedjemankh from the Metropolitan Museum of Art that was eventually repatriated to Egypt the following year.

The gilded coffin of Nedjemankh. Photo courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Investigators say Lotfi’s role as a whistleblower gave him an inflated sense of confidence that his own illicit activity would never be uncovered.

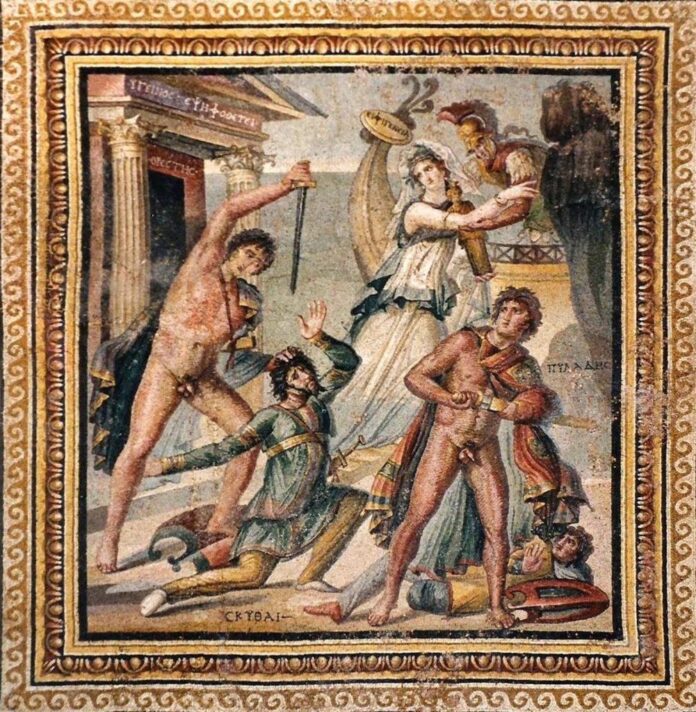

Now Lotfi, who is 81 years old, is charged with criminal possession of stolen property. A total of 24 objects were seized from him, including 23 mosaics from Syria and Lebanon and a 1,500-pound carved limestone sculpture referred to as the Palmyra Stone. The individual items range in value from $20,000 to $2.5 million, the affidavit said.

Artnet News was not immediately able to contact Lotfi for comment. But he told the : “I was fighting with them for 10 years to stop illicit trading, and they turned against me. I am not a smuggler. I am a collector.”

The address listed on the warrant is a post office box in Tripoli, but Lotfi at one time owned an apartment on Fifth Avenue so he could be close to the Met, according to the(The Met’s address is 1000 Fifth Avenue, and an online search for Lotfi turned up an address at 1001 Fifth Avenue, though the associated phone number listed is not in service.)

According to the extensively detailed warrant, a copy of which was provided to Artnet News, the Manhattan district attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit’s (ATU) investigation into Lotfi began “indirectly” in July 2017, when the unit applied for a search warrant to seize a $12 million marble bull head from the Met.

The head had been excavated from the archeological site of Eshmun in Lebanon amid its decades-long civil war, and was subsequently loaned to the Met. According to the warrant, Lofti was listed on loan paperwork as “the first documented possessor” of the artwork.

Palmyra Stone. Image courtesy Manhattan District Attorney.

It isn’t the only stolen Lebanese antiquity possessed by him, investigators say. Later the same year, a $10 million marble torso appeared on the market. Like the bull’s head, it had also been excavated from Eshmun during the civil war before Lotfi took possession of it. In November 2017 the ATU seized the object from his Fifth Avenue apartment after obtaining a search warrant. Both the bull’s head and the torso were repatriated to Lebanon in December of that year.

Then, in 2018, a third Eshmun antiquity with the same provenance was recovered by Lebanese customs officials from a container that Lotfi had shipped from New York to Tripoli. In an email from January that year, Lotfi told the ATU that he purchased the three objects in the 1980s from a dealer named Farid Ziade. Lotfi also told Homeland Security special agent Robert Mancene that he purchased other antiquities from Ziade during the civil war, including five of the 24 in total that were seized.

Over its years-long investigation, the ATU ”has developed additional evidence that the Defendant knowingly possessed stolen antiquities,” the warrant states.

Telete Mosaic. Image via Manhattan District Attorney

Mancene said that during his numerous interactions with Lotfi, the dealer demonstrated not only his intimate knowledge of the illegal trade in antiquities from the Middle East and North Africa, but also his “acute awareness” of the hallmarks of looted antiquities. He also knew from Lotfi that the hundreds of antiquities in his collection were scattered across across apartments in New York, Paris, Tripoli, and Dubai, as well as at several storage units in New Jersey.

Over the course of the investigation, Mancene said he learned that between 2008 and 2011, Lotfi “trafficked in Libyan antiquities; specifically, the distinctive legless funerary statues originating from the region of Cyrenaica, on the coast of eastern Libya.”

Furthermore, to facilitate selling the looted Libyan antiquities, Lotfi allegedly created a false paper trail using the Art Loss Register.

“I know, based on my experience in prior investigations, that antiquities traffickers often use the ALR to increase the value of their looted goods,” according to Mancene.

Mancene also says photographs of one of Lotfi’s shipping containers depicted objects “on a dirt ground surrounded by earth and rubble and with its surface encrusted with dirt,” a tell-tale sign of having been looted. Another photo showed mosaics on sheets of cloth which “are used to lift mosaics from the ground,” according to the warrant.