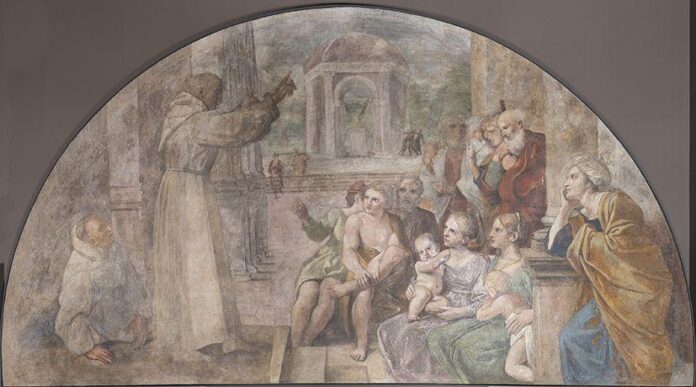

In the early 17th century, the Italian artist Annibale Carracci (1560-1609) was commissioned by the wealthy Spanish banker, Juan Enríquez de Herrera, to decorate his family chapel in Rome. The artist fell gravely ill shortly after and entrusted his assistants, under the supervision of Francesco Albani, with completing the project. The result was a lavish cycle of frescoes to match the stunning masterpieces Carracci had created for the Palazzo Farnese in Rome just a few years earlier.

Until recently, modern viewers have been forced to imagine what the assemblage—which is dedicated to Saint Didacus of Alcalá and depicts biblical subjects as well as everyday scenes—looked like in its entirety. The Herrera Chapel in the Church of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli was dismantled 200 years ago, and Carracci’s works were removed from the walls and shipped off to Spain to be stored in the deposits of two different museums.

Now, the frescoes have been reunited for what its organisers have called a “momentous” trio of exhibitions. Following displays at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid and the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (MNAC) in Barcelona earlier this year, the works are being shown at Rome’s Palazzo Barberini this month. The exhibition marks their grand return to the city in which they were conceived.

“We had been considering bringing together the frescoes for this exhibition for over 20 years,” says the Prado’s Andrés Úbeda, who has curated the exhibition. “This is the great unknown work in Carracci’s oeuvre. Seeing it intact means it can now be studied, researched and reassessed.”

The frescoes and Saint Didacus of Alcalá Presenting Juan de Herrera’s Son to Christ (around 1606), an impressive altarpiece Carracci created for the same church, remained in their original setting until 1830. That year, the chapel was destroyed and the works moved to the church of Santa Maria in Monserrato degli Spagnoli. The Didacus altarpiece remained at the church, while seven of the frescoes were moved to the Prado and nine to MNAC. A further three fragments are missing.

The frescoes stored at the Prado had to be restored before all the works could be reunited. (Those in Barcelona and Rome had been restored some years earlier.) The Prado procrastinated for years because it lacked the resources and expertise, Úbeda says. In 2012 it finally appointed an external expert for the three year restoration project.

While organising the show with three art institutions in two different countries was “extraordinarily difficult”, the rewards have been great, according to Úbeda. Each of the venues has displayed the 16 frescoes differently, allowing visitors to view them from a variety of perspectives. In Madrid, the works were shown sequentially along the walls, meaning museum-goers could get up close. They were arranged more abstractly in Barcelona, on a metal grid that gave the impression they were floating in mid-air.

Mixed condition

The Palazzo Barberini has opted to distribute the works in the vast Sala dei Marmi—a space with 16m-tall walls—in efforts to evoke the dimensions and layout of the Herrera Chapel. “We are aiming to re-create the original relationship between the viewers and the works,” says Flaminia Gennari Santori, the director of the Galleria Nazionale di Arte Antica, which comprises both the Palazzo Barberini and the Palazzo Corsini. “This is one of the few museums where it is possible to put on an exhibition like this.”

Even after the restoration, the frescoes are in a “mixed condition”, Úbeda says. One depicting San Diego saving a child who has fallen asleep in an oven, for example, was damaged when the curved fragment was removed from the wall and flattened out. Even so, the exhibition has proved wrong scholars who had written off the works, Úbeda says. “They are not in the best shape, but they are far from destroyed.”

According to Gennari Santori, the show also sheds light on the workings of Carracci and his assistants—“the greatest workshop in Rome”—and especially Albani’s central role within it. Once Carracci had withdrawn from the project, his assistants achieved a “highly unitary style”: a testimony to their autonomy, skill and mastery. “After his incredible frescoes at the Palazzo Farnese, Carracci’s assistants managed to rapidly produce something similarly grandiose,” Gennari Santori says. “That is no small feat.”

• Carracci: the Herrera Chapel, Palazzo Barberini, Rome, 17 November-

5 February 2023