In the 1940s, while New York City was cementing its reputation as the art world’s centre of gravity, both creatively and financially, there was another gravitational pull, almost 5,000 miles away, that has only recently begun to show its potential on the global market.

Brazil may not be the first art hub that comes to mind for the average denizen of the collector-class. But São Paolo is as much an epicentre for art as New York, London, Paris or Seoul. Its distance from those hubs, and crippling import tax laws, have kept many Brazilian collectors close to home. But even then, Brazil is massive, just shy of the Unites States in square mileage. Collectors and gallerists in the country pride themselves on the diversity of art produced in the Brazil’s varied regions, and that diversity and creativity has been increasingly present in the art market, especially after a few notable Brazilian galleries have expanded to or set up shop in New York City.

“Brazil has a solid market, especially in the last two decades,” says Daniel Roesler of Galeria Nara Roesler, which has locations in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and New York. One could argue that Brazil’s art market began taking shape in the 1940s with the collectors and patrons Assis Chateaubriand and Ciccillo Matarazzo, both of whom brought distinguished European collections to Brazil and founded institutions that helped make Brazil’s art scene what it is today. Chateaubriand founded the Museu de Arte de São Paulo in 1947, and Matarazzo organised the Bienal de São Paulo, the second oldest biennial in the world, and the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo.

Roesler, like several gallerists from Latin America whose programmes would exist relatively sub rosa unless they were showing at a major fair, chose to expand to New York City and bring Brazilian artists to a wider audience. “We wanted to be closer to the collectors we had been developing through the years at national art fairs,” he says. “We wanted to be closer to the institutions in New York, closer to what in our mind is the main hub of art in the world. So, we took this this challenge that had never been done before. A Brazilian gallery opening a branch space in New York.” That was in 2016. Galeria Nara Roesler’s first space was a small office in the Flower District. As their client list grew, so did their space. After a stint on the Upper East Side the gallery has settled into a chic space on West 21st Street in prime Chelsea.

“Brazilian collections are very much focused on Brazilian art,” Roesler says. “Partly because it is so difficult to import art in Brazil, it’s very expensive because of taxes. But that has turned the focus here on Brazilian production, and our history, and strengthened the understanding of the local reality. There are really great collections, very sophisticated collections, that are based on resident art.”

Despite its semi-insular quality, Brazil’s art market has been affected by the rapid development of technology forced on the art world because of the Covid-19 pandemic. “Since we began in 2018, we have been expanding to meet the demands of the market,” says São Paulo-based collector and advisor Camila Yunes. “In these four years we have seen a representative increase of young collectors—in general, members of the Millennial Generation, who are aged between 30 and 40 years. That change in profile is accompanied by a change in behaviour—collectors are more involved and engaged about their role in promoting their own market.”

This cadre of Millennial collectors has also embraced digital art and virtual viewing rooms, in part because the pandemic all but stopped in-person gallery visits. But, according to Luciana Brito of Luciana Brito Galeria in São Paulo, “art fairs continue to play an important role, so much so that in recent years we have seen an increase in the number of these events in Brazil”.

SP-Arte, the fair founded by the collector Fernanda Feitosa in 2005, has helped internationalise the collections in Brazil, in large part because the São Paulo state government in 2017 mercifully reduced the exceptionally high taxes—which are regularly between 50% and 60%—for artworks brought into the fair. As a result, more fairs have popped up, including ArtRio and Art Sampa, which debuted in March 2022.

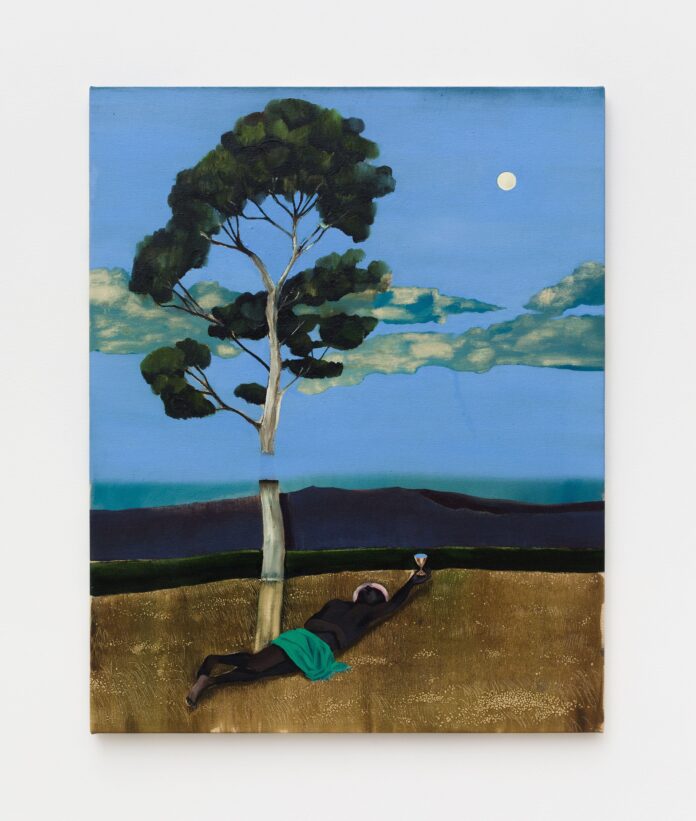

The Brazilian contemporary artists who garner the most market attention range from Antonio Obá, Arjan Martins and Gustavo Caboco, who include in their practice current issues related to the decolonial discourse, to painters Marina Perez Simão and No Martins. “The last few years have been challenging and, above all, have shown the galleries and the contemporary art market’s capacity for flexibility and reinvention in times of great restrictions,” says Victoria Zuffo, president of the Brazilian Association of Contemporary Art Galleries (ABACT). “In Brazil, the pandemic period recorded excellent sales figures, and the strengthening of the virtual action of galleries and events has brought a large portion of new buyers, with a younger profile, all highly attuned, informed and connected, closer to art.”

However, like in most places, the newest technology could not replace the importance of in-person events. “The whole atmosphere surrounding fairs and exhibitions is extremely important,” Zuffo says, “but we also noticed that virtual platforms are important as an agent to bring people closer to the art or the artist, they are like the kick-off for a conversation that may be finalised in person. In other words, the hybrid format is here to stay.”