When Frieze Los Angeles opens to the public this week, cultural stakeholders from all over will swarm the Santa Monica airport, seeking an intelligible narrative about the state of contemporary art—in a city famous for its lack of a coherent center.

Indeed, L.A.’s marquee art institutions seem to be presenting very different pictures of what matters now. The Getty is devoting its contemporary show to conceptual photographer Uta Barth, while the Hammer celebrates Joan Didion and LACMA exhibits recent abstract acquisitions and artworks that trace African diasporic legacies.

L.A. gallerists, curators, and artists, too, have disparate ideas about which aesthetics are trending locally. If they can agree on one thing, however, it seems to be that artists are responding to or against the figurative mode that has, for nearly a decade, dominated contemporary art discourse.

Daniel Gibson, (2022). Courtesy of Shulamit Nazarian, Los Angeles.

“There’s a loosening up of paint styles in general,” said Esther Kim Varet, founder at Various Small Fires. Over the past couple years, Joshua Nathanson, one of her L.A.-based artists, has foregone stark, cartoonish outlines for hazy figures that blend with their backgrounds. This looser style has a reach far beyond the city’s limits. For Frieze’s online viewing room, Kim Varet will exhibit work by two other painters, Alvin Ong (based in London and Singapore) and Alex Foxton (Paris), who have also embraced more languid brushstrokes.

The gallerist speculates that she and her collectors might be drawn to this kind of atmospheric work at this particular moment, valuing their own emotional responses more than they did pre-pandemic. Her client base is responding to “mood” and “loveliness” again, she says—to painting qua painting. Figurative work hasn’t completely disappeared, and abstraction hasn’t yet made a full-force comeback, but people are “getting a little more emotional” these days.

“It might be a pivot point,” she speculated. “There are so many other factors. My client base in Asia really loves figurative painting. Shifts and trends are really complex.”

Ken Gun Min, (2022). Courtesy of Shulamit Nazarian, Los Angeles.

Seth Curcio, partner at Shulamit Nazarian, believes the pandemic has inspired local artists to move away from the figure as well, but in a different direction—towards landscape.

As indoor spaces shuttered across Los Angeles, artists meandered across hiking trails and their own neighborhoods, transmuting these experiences into new compositions. “Artists are using landscape to talk about social and cultural ideas,” Curcio said. They’re trying to “think about the world outside their studio and the world they’re building inside their studio, on their canvases.”

As an example, Curcio cited the paintings of gallery artist Daniel Gibson, a local, whose “lush, psychedelic landscapes” feature imaginary deserts and very real, embedded concerns about migration and borders. Ken Gun Min, who settled in Los Angeles after living in Asia and Europe, creates imagined landscapes rooted in specific local sites: Buena Vista Park, Runyon Canyon, and Silverlake have all appeared in his canvases, transformed into queer utopias via thread, vintage beads, oil paint, and Korean pigment powder.

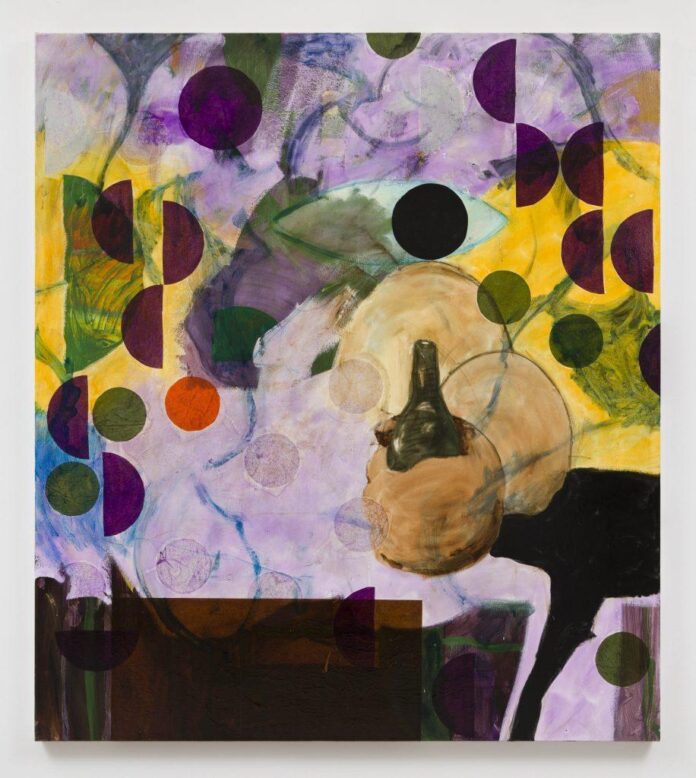

Annie Lapin, (2022). Courtesy of Shulamit Nazarian, Los Angeles.

Finally, Annie Lapin amalgamates and digitally alters photographs and art historical imagery to create her own surreal, fragmented landscapes that evoke memories and dreams. According to Curcio, these artists are now thinking about the world in a way that’s dislodged from the body. “Landscape is a really fertile place to map those emotions,” he said.

Artist Nick Doyle also sees L.A. artists turning away from the body—but towards objects.

An Angeleno now based in New York, Doyle will exhibit collaged-denim-on-panel wall sockets at Reyes Finn’s Felix Art Fair presentation. He mentioned the work of local painters Mario Ayala, Sayre Gomez, and Kara Joselyn as emblematic of a flattened, airbrushed style that simultaneously references three major features of the Los Angeles landscape: cars, street signs, and film sets. The theatrical paintings of Justin John Green, he said, embrace a “romantic, Hollywood-esque quality.”

Nick Doyle, (2023). Courtesy of Reyes Finn.

Doyle appreciates the atmospheric influences of the West and his hometown’s art history, relatively untethered to the intense East Coast legacies of minimalism and conceptualism. “What makes L.A.’s art scene interesting is that it’s unattached to longer art historical lineages and has room to expand into other visual languages,” he said.

Zoe Lukov, cofounder at nonprofit Art in Common, also sees an environmentally conscious, surrealist trend rippling across the city’s art scene. “There’s proximity to film and major climate disaster,” she said. “It’s a surreal combination.”

Local artists are especially interested in themes related to the water, she finds. Fawn Rogers, Lukov noted, makes “lush, sexy paintings, often of oysters,” while Nicolette Miskhan’s canvases feature mermaids, undermining old tropes that have made the fantastical figures repositories “for shame, desire, and fear about the feminine.” Via performance, Deborah Scacco examines the body’s relationship to water. (During Frieze week, Art in Common will mount “Boil, Toil, and Trouble,” featuring work by all three artists.)

Nicolette Mishkan, The Protection Circle (2022). Photo: Anita Posada. Courtesy of Art in Common.

For his part, Felix Art Fair founder Dean Valentine believes the recent surrealist fad, along with the figurative arc, is coming to an end—at least from a market standpoint. “I think people are waiting to see what’s next,” he acknowledged. “I don’t think anyone’s seen over the horizon yet.”

If anything, he said, there’s a stronger disposition, among painters, towards “pleasingly colorful work.” Like Kim Varet, he thinks that collectors are turning towards more beautiful art. He conjectures that it’s an escape from worries about a slowing economy, conflict in Ukraine, climate change, and other global stressors.

Valentine believes that as the city’s art scene has become ever-more global—as international blue chip galleries set up shop and the stylistic influence of artists and influential educators such as John Baldessari, Chris Burden, and Mike Kelley becomes more diluted—“L.A. art” loses some of its regional flavor.

Fawn Rogers, Happy as a Clam (top) and The Most Beautiful Pearls Are Black (bottom, both 2021). Photo: Anita Posada. Courtesy of Art in Common.

Art advisor Irina Stark, on the other hand, continues to be astounded by the amount of painting in the city, thanks in part to its fantastic light. She noted a number of contemporary painters who have relocated to Los Angeles and made the city their home: Katherina Olschbaur, Simphiwe Ndzube (exhibiting in the Art in Common show), Veronica Fernandez (showing in Frieze Focus), Anna Valdez, Jonny Negron, Tala Madani (whose work is up at MOCA), Jill Mulleady, Katja Seib, and Claire Tabouret.

Stark sees artists moving towards abstraction, but she also believes that ceramics and surrealism are still going strong. Like Lukov, she sees a “love for witchiness” across the city: “We’ve had figuration as a main trend for eight years, so I think it’s time to incorporate something new.”

Debra Scacco, Channel (n.d.). Photo: Anita Posada. Courtesy of Art in Common.

Though painting trends may dominate the conversation, ICA curator Amanda Sroka is focused on performance. Her institution just opened three solo exhibitions devoted to artists who explore sound: Jacqueline Kyomi Gork, Milford Graves, and Christine Sun Kim.

Sroka moved to Los Angeles this year and is still acquainting herself with the local art scene. “There is a real, thriving performance community here in Los Angeles,” she said, thanks to the L.A. spaces that support the medium (MOCA will also host Simone Forti dance performances during the fair week).

Sroka also sees local artists using organic materials, integrating the earth into their practices—but she’s hesitant about calling out specific trends. Having just arrived, she is still wrapping her head around her new home.

“Los Angeles is dizzying and intoxicating,” she said. “As soon as you have your hand on the pulse of something, it’s changing.”