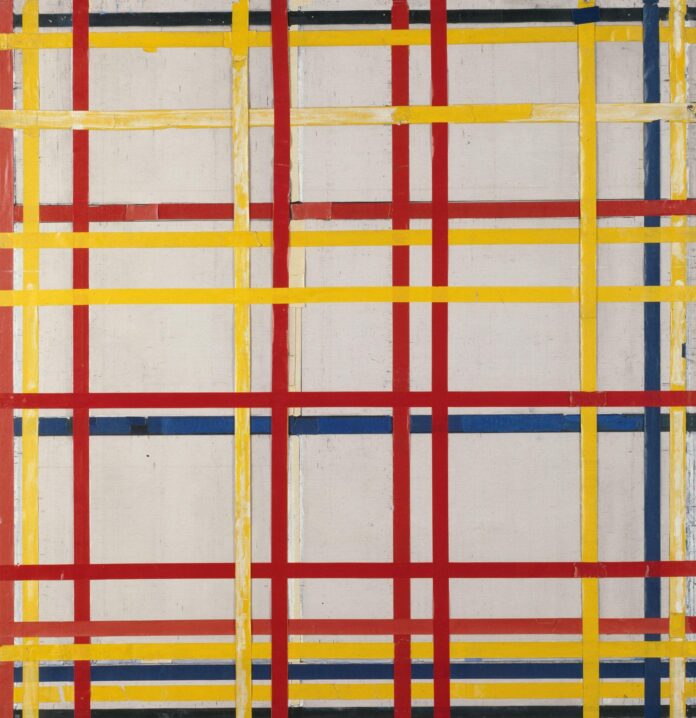

A key work from Piet Mondrian’s late period has potentially been hanging upside down for more than 75 years. The work by the Dutch artist (1872-1944) is included in a new exhibition, Mondrian: Evolution, which opened on Saturday at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Dusseldorf, Germany (until 12 February 2023).

New York City I (1941)—an abstract work composed of vertical and horizontal lines in red, yellow and blue—has been displayed with its five most densely spaced lines at the bottom of the picture since 1945. However, the work is orientated the other way in a photograph taken in Mondrian’s studio shortly after his death in 1944, showing the closely spaced lines at the top.

The exhibition’s co-curator, Susanne Meyer-Büser, suggests in the catalogue that “it may no longer be possible to determinewhether the orientation previously considered correctis in fact valid”. She adds that if the work is rotated 180 degrees—as seen in the 1944 photograph that was published in Town and Country magazine—“it functions extremely well: the composition gains in intensity and plasticity”.

An installation view of Mondrian: Evolution at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf. New York City 1 (1941) is displayed alongside Woods near Oele (1908) Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen; Kunstmuseum Den Haag

The work is not dated or signed by the artist and is likely unfinished. Mondrian appears to have been using the coloured strips of paper to work out the composition before then painting them in oil as seen in a similar work, New York City (1942), which is in the collection of the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Meyer-Büser compares this composition, with lines closely space at the top, to how New York City I should perhaps be displayed.

Furthermore, although the work has not undergone detailed conservation, Meyer-Büser writes that it appears that the strips of paper were first affixed to what is currently the bottom of the canvas and then worked up—when it would have been logical to start from the top and unfurl the tapes downwards. However, she caveats this theory with the possibility that the artist may have “repeatedly turned the picture around while he was working on it, in which case there would be no right or wrong orientation.”

Meyer-Büser told The Guardian newspaper last week that she is now “100% certain the picture is the wrong way around”. Despite this, the work will continue to be exhibited as it has been for the past seven for conservation reasons: “The adhesive tapes are already extremely loose and hanging by a thread […] “If you were to turn it upside down now, gravity would pull it into another direction.”

The correct way? Mondrian’s New York City I (1941) rotated 180 degrees as it may have originally been intended to be displayed © Mondrian/Holtzman Trust, c/o Beeldrecht, Amsterdam, Holland, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein Westfalen, Düsseldorf, photo: Walter Small, Dusseldorf

The independent curator Francesco Manacorda, who organised Tate Liverpool’s 2014 show Mondrian and His Studios, tells The Art Newspaper: “I have not reviewed all the documentary evidence (the picture in particular) that is used to support the statement, but for me the interesting aspect of the story is that these works were unfinished. This means that the artist’s intention is not set on them and as such they are hybrid and somehow more fragile in their status. If Mondrian had lived longer would he have finished them? How? All certainties around objects of this kind need to be taking into account […] I think these considerations also have an impact on the possible ‘mistake’.”

Mondrian experimented with various different styles throughout his career, but his most important and famous works are the pared-back abstract compositions from the 1920s and 30s created using vertical and horizontal lines in black and the three primary colours. New York City I was made after the artist moved to the US in 1940 and started making vibrant paintings primarily using red and yellow, eschewing the thick black lines of before. He began to add squares and dots running along the lines, mimicking cars driving through New York’s gridded streets, and adding a sense of movement to the works. The artist was also inspired by Boogie-woogie music and named several works after the genre.