Four years after the HMT Empire Windrush set sail in 1948, Aubrey Williams set foot in England.

Today, a room in Tate Britain is dedicated to Williams’s art, and he is remembered as a founding member of the influential Caribbean Artists’ Movement, the London group whose legacy is secure in the canon of British Modern art.

But, at the age of 26, Williams arrived in London in exile, a man already marked by the British government.

He was born and raised on an island colonised by the British. He grew up in Georgetown, in British Guiana, now Guyana, and showed artistic talent from a young age. His family were attendant at the local church, and Williams, before the age of ten, gained his first mentor in art; an aged Dutch man called Mr De Winter who restored the religious paintings that hung in the church. Williams’s father showed De Winter an early drawing by his son—of a vulture eating a rat in the street opposite their home. The skill of the drawing convinced the restorer to employ the young boy as an informal apprentice.

Williams was the son of a civil servant and the eldest of seven children. British Guiana was a big producer of the sugar that the British stir into their morning tea and the Demerara that they mix into their cake batter. Accordingly, Williams, when still a teenager, began to train as an agriculturist.

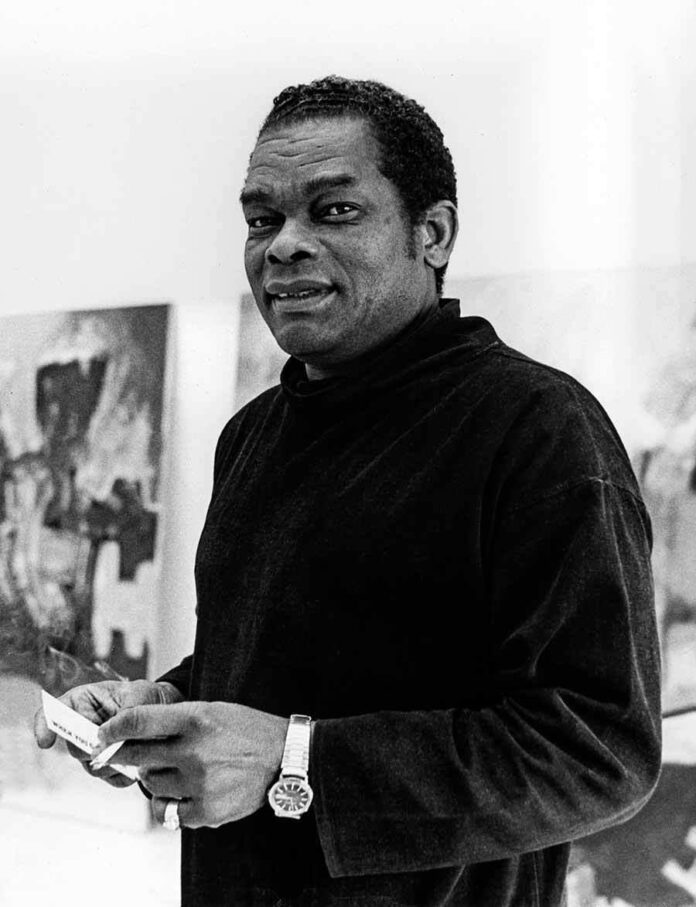

Aubrey Williams, Untitled, 1970 © Aubrey Williams Estate, courtesy October Gallery

He loved his work; the natural beauty of Guyana was the source of his early art. In Third Text, a published conversation between Williams and the Indian artist Rasheed Araeen, Williams said of Guyana: “I was born into a world in which there is a natural appreciation of excellence, and this permeated the whole society. It went down to the grassroots peasants in the country.”

After graduating, he secured a job as a field officer for the country’s agricultural department, where he was set to work on the sugarcane plantations on the eastern coast of the island. There, he began to mix with Indian labourers who had been brought, as a result of the British Empire, to work on the plantations in Guyana. Williams was fascinated by the skill the labourers exhibited in their work. “An Indian farmer would make his rice-paddies in certain ways that today we could call ‘artistic’,” he said to Araeen. “His mud fireplace would be like a piece of sculpture…they have their own profound concepts and behaviour patterns and iconography which gave them tremendous insight for handling the environment beautifully.”

But the farmers he met were “manipulated by the estates, cheated and exploited”, he said, adding: “They were always on their own, and there was no-one to intervene and help them.” And so, Williams began to organise, encouraging the exploited sugar farmers he met through his work to demand more labour rights from the almighty British owners of the plantations.

“I was breaking the rules left, right and centre,” Williams said. “I was battling with the government for the famers, while I was a cane-farming officer. I became the arbitrator-cum-organiser for the sugar farmers.”

His actions were not well received and led to Williams receiving an assignment that no-one else wanted: he was sent to work in Hosororo, a small, remote commune in the rainforested Barima-Waini region of northern Guyana, on the west bank of the Aruka River—a universe away from the urban amenities in Georgetown. He was required to work on an experimental crop development station, but instead became immersed in the lives of the Warrau Amerindians, an indigenous group who have lived, for centuries, in the rainforest.

Williams learned the customs and rituals of the Warrau, later ascribing the encounter as one of the most formative experiences in his life. Indeed, many of the ritualistic motifs that form the Warrau’s belief system are visible in the works that now hang in Tate Britain.

To accompany the exhibition Aubrey Williams: Future Conscious (until 29 July) at October Gallery in London, the Polish curator Jakub Gawkowski writes of Williams: “It is to this encounter with the Warrau that Williams ascribes his discovery of himself and his decision to dedicate his life to art.”

After two years in Hosororo, Williams returned to a Georgetown now alive with the idea of independence. Williams quickly became involved with the People’s Progressive Party, an insurgent political party which sought to spurn British colonialism and establish Guyana as its own state, free to determine its own future.

In Third Text, Williams described Guyana as “a boiling cauldron”. He said: “Guyana was coming out of colonial bondage. It was the time when the seed of independence began to germinate.”

When Williams returned Georgetown and continued his revolutionary politics, the government opened a dossier on him. Williams realised he had to leave Guyana for his own safety. And, in a dichotomous twist of fate, he realised his best way out of Guyana was on a boat to Britain, a country in need of immigrant labour.

Williams migrated to Britain in 1952. In Third Text, he remembers the racism he experienced on the street. “I came to a London where, in the pub, they would touch a black man for good luck,” he said. Shortly after his arrival, he gained a scholarship to read Agricultural Engineering at Leicester University. But, just as quickly, he dropped out of the course. The continent of Europe, and all its art, called. Williams used his travels to educate himself in the recent history and contemporary movements of Modern art, taking in the great museums in Italy and France. He even met Pablo Picasso, an experience he later reported as deeply underwhelming because the ageing Spanish great did not recognise the young Guyanese man as “a fellow artist”.

Williams returned to London intent on pursuing his real calling. He gained a position at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London and threw himself into the London art world. Two exhibitions, both at Tate, left a deep impression: Modern Art in the United States (1956) and New American Painting (1959) enabled him to see, first hand, the works of a new generation of mostly American artists—Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and Yves Kline—who, together, formed a movement known as Abstract Expressionism.

During that period, Williams began an obsessive relationship with Dmitri Shostakovich, and would listen to the symphonies and string quartets of the 20th-century Russian composer while he painted.

The work on show at the Tate today demonstrates Williams’s immersion into the theories of Abstract Expressionism, coupled with his deeply emotional connection to Shostakovich and the ancient beliefs of the Warrau group, as well as the bucolic Guyanese rainforests in which they lived in careful harmony.

But how was it received?

Williams did not live a life of total obscurity. In 1963, he won first prize in the first Commonwealth Biennale of Abstract Art, a London-based exhibition which featured artists from Commonwealth countries, many of whom had settled in Britain over the course of the preceding decade. He later became a leading light in the Caribbean Artists Movement, which operated in London between 1966 and 1972 and offered an outlet for the work of creatives from the Caribbean diaspora, including visual artists, writers, filmmakers and musicians such as Stuart Hall, Orlando Patterson and Edward Kamau Brathwaite.

Writing in the Camden New Journal Review, Angela Cobbinah, the pioneering writer who primarily explored the stories of female artists from the African diaspora, said of the Caribbean Artists Movement: “It had an enormous impact on Caribbean arts in Britain. In its intense five-year existence it set the dominant artistic trends, at the same time forging a bridge between West Indian migrants and those who came to be known as black Britons.”

But Williams soon began to fall out of favour. The big institutions politely but consistently passed up the opportunity to display his work, and Williams, as a now mature artist, was left to exhibit in poorly attended fringe galleries. He increasingly felt marginalised and isolated from the mainstream art world, working more and more in privacy and without much hope of recognition.

Williams met Chili Hawes, the founder of October Gallery in London’s Holborn, in the early 1980s. With Hawes’s help, he began to be recognised anew. After a series of exhibitions at October Gallery, he was represented in The Other Story, a group exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1989. But, just as London’s institutions were waking up to the generational talent working in their midst, Williams was dealing with a terminal cancer diagnosis. He died shortly after, in 1990.

Hawes was instrumental in Tate Britain recognising Williams’s unique contribution to British art. His work was initially included in the group show Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s in 2021/22.

But she continued the conversation with Tate, and, after the recent rehang, Tate Britain now dedicates an entire room to Williams; titled Aubrey Williams: Cosmological Abstractions, 1973–85, the display consists of paintings created just as the artist felt most despairing of an art world that remained cold to his talents; perhaps because of his background.

For the troubled young artist who stepped off the boat in England as part of the Windrush generation, it is a recognition long overdue.