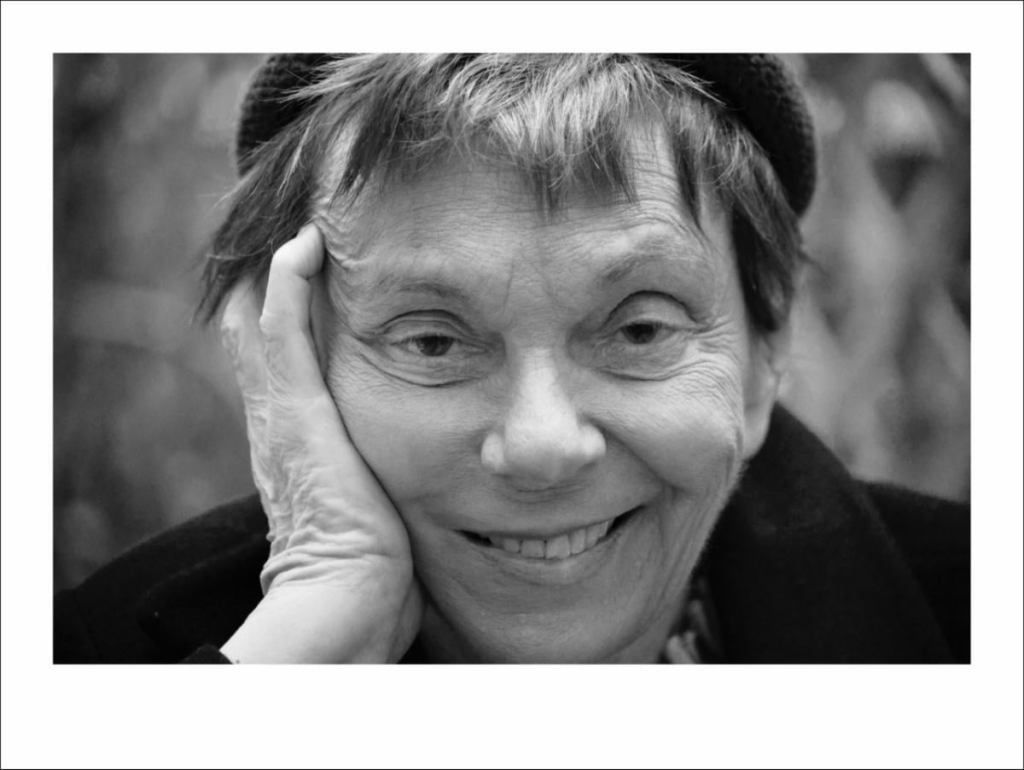

Mary Beth Edelson is an artist who has used her work to raise awareness of the feminist movement and empower women. She died at the age of 88. The David Lewis Gallery in New York, which presents her, has confirmed her death.

Mary Beth’s accomplishments as a pioneering feminist artist and activist continue to change the course of art history. Since the 1970s, Edelson has created photographs, sculptures, and collaborative projects that were conceived as a response to centuries of exploitation and enslavement of women. In her art, women attained the status of goddesses, and networks of female artists were formed.

Edelson was an integral figure in 70s feminist art circles. She achieved a late rise in her career after her work was recognized for innovative initiatives alongside works by contemporaries such as Ana Mendieta and Hannah Wilke.

In her most famous work, the collage Some Living American Artists / The Last Supper (1972), Edelson adopted Leonardo da Vinci’s famous depiction of the last feast of Christ and replaced the painted male disciples with photographs of female artists.

Later reproduced as a print, the work features Georgia O’Keeffe as Jesus; Alma Thomas, Yoko Ono, Louise Nevelson, Helen Frankenthaler, and others gather beside her. Edelson added a border to that scene, collaging even more than 60 images of other women artists.

Edelson continued to appropriate the famous Old Master paintings, reworking them, combining female artists and thinkers instead of male figures, and again creating a border with images of even more women, as she did with two 1976 paintings: Death of Patriarchy / A.I.R. Anatomy lesson and happy birthday, America. All three colleges are now in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In her most famous series, Woman’s Rise, launched in 1973, Edelson went beyond these feminist expressions. In it, Edelson photographed herself naked in poses in which she held her breasts or spread her legs so that her vagina was visible.

To these paintings, Edelson added collage images and painted elements that gave the work a mystical touch. Produced two years before film scholar Laura Mulvey theorized the male gaze, these photographs undo the subjugation of women’s sexuality and imagine power from a female perspective.

Edelson once wrote that she also used her body as a found object in her early works. On another occasion, she said that she presented herself as a powerful object of human self-determination in this body.

In another series called Monstre Sacré, also launched in 1973, Edelson further advanced the spiritual themes of her art, this time combining her work with the multi-armed Hindu goddess Kali. Edelson became interested in Jungian psychology but eventually abandoned it, retaining an interest only in its archetypes. With the help of these works, she “summoned the Goddess to call her at home.”

Edelson’s work has long been considered key for feminist art experts and members of the movement in the 70s. But her art did not receive widespread attention until the last two decades. Then, it was featured in several major institutional studies.

In a 2019 Artforum essay, critic Dodie Bellamy attributed this surge of interest to Edelson’s reliance on goddesses for her work. Bellamy wrote that if he had known Edelson in the 1980s, her confidence and rights would have served him well.

Feminist artist, Mary Beth Edelson

Mary Beth Johnson was born in 1933. She studied art and then briefly joined a traveling contemporary dance troupe. But she soon left her to attend New York University for a master’s degree in the late 1950s.

Edelson taught briefly at Montclair State College in New Jersey and then left because she felt there were not enough opportunities for female professors.

Edelson then moved to Indianapolis, where she immersed herself in activist circles, studying the organization’s strategies and developing an interest in the fight for civil rights.

She got married in 1965. Together with her husband Alfred H. Edelson she founded a gallery there.

In 1968, Edelson left the city with Alfred. She later divorced and moved to Washington, DC.

In 1972, Edelson hosted the first National Conference of Women in the Visual Arts at the Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington, DC, an event designed to raise awareness among participants. Speakers at the event included artists Judy Chicago, Elaine de Kooning, Alice Neal, and Miriam Shapiro, and art historian Linda Nochlin.

In 1973, in a conference report, Edelson wrote that thanks to our new identity and constant reappraisal, we are transforming. Edelson explored how women can work together to form communities and write previously unspoken stories.

In her book Story Collection Boxes, begun in 1972, Edelson asked respondents to ask questions about gender, including questions such as “HOW WAS IT TO BE A BOY?” and “WHAT DOES YOU FATHER TEACH YOU ABOUT WOMEN?”

Edelson was also a member of two feminist collectives credited with shaping the art of that era. She was associated with a New York gallery run by women who formed what is considered the first feminist art collective in the United States. It gave Edelson one of her first solo exhibitions under the playful title “Five Years Retrospective”.

And in 1977 she co-founded the influential Heresies Collective, which published a magazine dedicated to issues such as Third World feminism and lesbian art. Edelson’s later work looked at a number of female images that were widely covered in magazines and films.

In her 1993 film Lorena Bobbitt’s Last Temptation, Edelson focuses on Lorena Bobbitt, who gained media attention in 1989 when she cut off her abusive husband’s penis while he slept. Edelson reimagines this act of violence as a religious scene – Pieta, in which Bobbit’s husband, relaxed, lies on her lap, bleeding. The image is framed by images of penises attached to a black plastic chain. Subject later reported Kali / Bobbitt (1994), a sculpture depicting Bobbit as a Hindu goddess wearing an S&M costume.

Cali / Bobbitt was unforgettably featured at the 2015 MoMA PS1 Greater New York Triennial, and it was just one of many performances by Edelson on famous shows.

Her art featured in a survey of 1970s feminist art organized by the Vienna Werbund Collection, which still travels the world today, and Art After the Stone Wall, 1969-1989, which appeared at the Columbus Museum in Ohio. , The Frost Museum of Art in Miami, and the Gray Art Gallery, and the Leslie-Loman Museum in New York from 2019 to 2020.

Traveling retrospectives of her work were held in 1989 and 2006 in the United States and Sweden, respectively. These shows helped build an Edelson fan base. When the David Lewis Gallery reviewed 1970s Edelson’s work in 2019, New York Times critic Robert Smith wrote, “Of course my amazement is not unique.”