Using lead isotopic analysis, researchers have identified a source of copper in ancient Egypt during the upheaval. The new study was published by a group led by Shirley Ben-Dor Evian in the Journal of Archaeological Science. It shows that material found inside four 3,000-year-old bronze burial figurines called ushabtis came from the Arabah region in the area south of what is now Israel.

The inclusion of copper is potential evidence that civilization continued to flourish during the little-studied era known as the Third Intermediate Period. It lasted from 1070 BC. E. To 664 BC e. This latest study shows that a copper exchange network existed between the Egyptians and the Arabah region, which continued to work even as other neighboring empires collapsed around Egypt.

Ben-Dor Evian is the curator of Egyptian archeology at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. She collaborated with researchers from Tel Aviv University and the Israel Geological Survey.

She says the new study shows that despite internal divisions within Egypt and the decline of empires in the ancient Middle East, Egypt continued to play a significant role in the region. She also noted that the study would help identify materials from the Timna and Feinan copper mines. They date back to the Third Intermediate Egyptian Period.

Ushabti was a common inventory in ancient Egypt. They were believed to perform any work required in the afterlife on behalf of the deceased. The four royal ushabtis were examined by Ben-Dor Evian and her team and the Israel Museum. They were discovered in Tanis, the capital of the pharaoh, and date from the reign of Psusennes I. He ruled from 1056 to 1010 BC. E.

The third interim period was a time of uncertainty and divided rule for Egypt, which faced numerous invasions and political upheavals, with a split kingdom ruled by a pharaoh in Lower Egypt and a high priest in Upper Egypt. Despite this, Psusennes was able to import copper from the thriving industry in Arabah, and these connections may even have allowed the metal arts to flourish in Egypt at the time.

After Psusennes, Pharaoh Sheshonk I invaded Arabu as part of his campaign to unify Egypt, possibly to control the supply of copper himself. But the statuettes prove the existence of trade routes that existed before the reign of Sheshonk I, potentially showing that Egypt did not become as isolationist as previously thought.

The largest archaeological finds in recent years

Egyptian archaeologists have discovered a giant brewery more than 5 thousand years old. Scientists suspect it is the oldest brewery of its size ever known.

The brewery was found by a team of archaeologists from Egypt and the United States in the ancient city of Abydos, an important archaeological site located on the left bank of the Nile north of Luxor.

At the same time, this brewery could produce about 22,400 liters of beer, said one of the leaders of the archaeological mission, Matthew Adams, a specialist from New York. According to archaeologists, the brewery was built during the reign of Pharaoh Narmer, famous for founding the first dynasty of the Early Kingdom (3150-2686 BC) and for its role in uniting Upper and Lower Egypt.

According to Adams, it was no coincidence that Abydos, one of the oldest cities in Ancient Egypt, where large temples and extensive burials were found, were chosen as the site for the construction of the brewery.

During archaeological excavations, scientists have already found signs that beer was used during mourning rituals in these places, the ministry of antiquities said in a statement. The ancient brewery is not the first important find for archaeological science in Egypt this year.

In early February, archaeologists discovered 16 mummies near Alexandria, which had golden tongue-shaped amulets in their mouths.

The ancient Egyptians thought that in this way the departed would be able to speak at the Judgment of the Dead before the judge, the god Osiris.

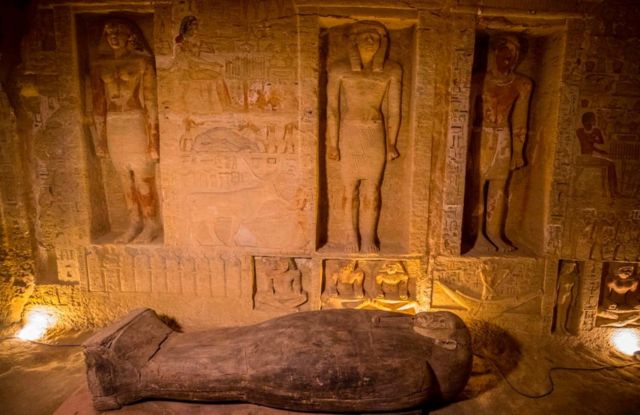

Last year, 59 well-preserved sarcophagi with mummies and 28 wooden statues of ancient Egyptian gods were discovered in the Sakkara necropolis near Cairo.

This previously unknown burial was announced by the Minister of Tourism and Antiquities of Egypt, Khalid al-Anani. According to him, despite the fact that the burial is 26 centuries old, the remains and sarcophagi are well preserved.

Some of the sarcophaguses are painted. According to the minister, they will be exhibited at the Great Egyptian Museum, near the pyramids in Giza. Almost all sarcophaguses contain mummies of clergy and high-ranking officials.

The sarcophagi were found in three specially made mines and were located one above the other.

The sarcophaguses stayed untouched for two and a half thousand years. What other mummies have been resting in Sakkara for more than two thousand years is still unknown.

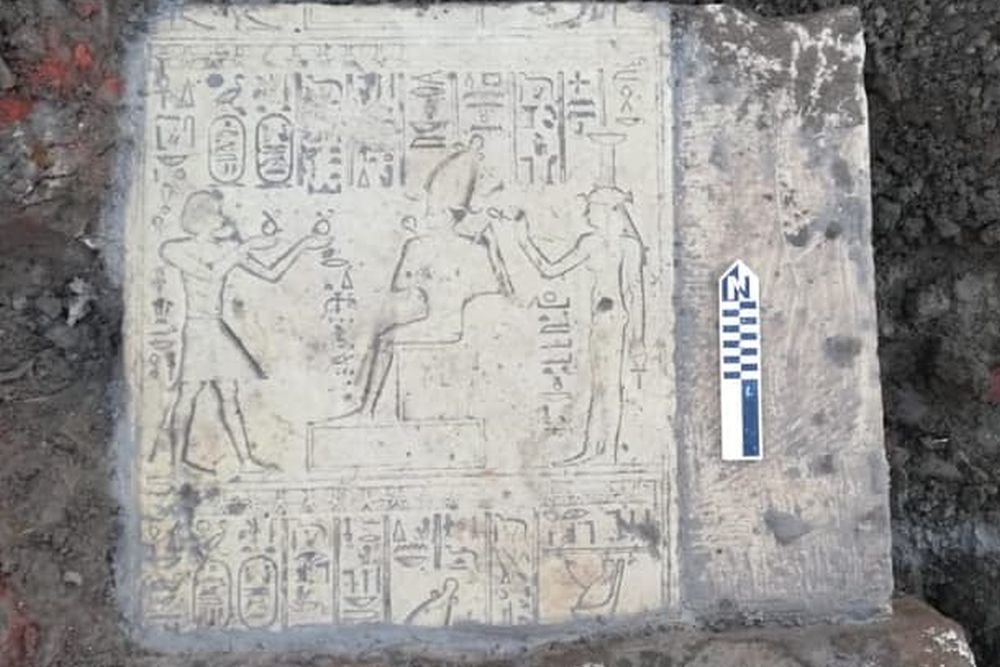

In Egypt, archaeologists during excavations in the village of Kom Ashkau near the city of Sohag discovered five limestone slabs with images of the gods at once.

According to the Archeology News Network, citing the head of Egypt’s Supreme Council for Antiquities, Mustafa Waziri, the slabs were discovered in the recently found temple of Ptolemy IV (221-204 BC).

Perhaps, under Ptolemy IV, they were simply transferred to another temple. The sanctuary in which the plates were originally located, presumably, was dedicated to the god Osiris, the king of the afterlife and the judge of the souls of the departed.

One of the blocks appears to have been part of the façade of the sanctuary, as it is decorated with patterns. The second block illustrates a scene in which Ptolemy I offers clothes to Osiris.

A similar picture is depicted on the third plate, only, in this case, Ptolemy I offers a necklace to the king of the underworld. It also depicts Isis standing behind Osiris – one of the most revered goddesses of Ancient Egypt.

She was considered the wife of Osiris. By the way, according to mythology, she was the mother of Horus, the god of the sky and the sun. Consequently, she was also the mother of all the pharaohs, since they were considered the earthly incarnation of Horus.

The images on the two remaining slabs are only fragmentary. Scientists believe that scenes of Ptolemy I’s offerings to the god Osiris could also have been carved on them.

The “lost city of gold” was excavated 3 thousand years old.

Archaeologists have unearthed a lost city in Egypt, which is about three thousand years old. Aton is the oldest settlement ever found in Egypt and one of the main finds for archaeological science.

The Egyptian city dates back to the reign of Amenhotep III, one of the most powerful pharaohs in Egypt, who ruled from 1391 to 1353 BC. It also continued to be used by the pharaohs Ai and Tutankhamun.

“The Lost City is the second most important archaeological discovery since the tomb of Tutankhamun,” said Betsy Brian, professor of Egyptology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. According to her, the discovery will give scientists a rare opportunity to “look into the life of the ancient Egyptians” during the heyday of the empire.

During the excavations, archaeologists discovered many valuable archaeological finds – jewelry, colored ceramics, amulets in the form of scarab beetles, and bricks with the seals of Amenhotep III.

According to Zaha Gavassa, excavations continue at the site of the found city. Archaeologists hope to find treasure tombs there.

By the way, Egypt is keen to popularize its long-standing legacy in order to revive the tourism sector, which has suffered after several years of political turbulence and the coronavirus pandemic.