Creators in history have depended on potent contrast to reflect the dual nature of passionate love: how else to convey its simultaneous depths of pain and heights of pleasure but through stark black and white? The poet Frank O’Hara in his 1950s magnum opus Meditations in an Emergency summoned the image of a pale white glow to Saint Serapion’s post-mortem countenance—realized in paint most essentially by Francisco de Zurbarán—to explain the acute euphoria and doom he feels when kissing the “one man” he adores “unshaven.” For O’Hara and his artistic offspring, this mimetic contrast between black and white, generating a singular heat akin to a Zurbarán chiaroscuro, has immortalized passions personal and cultural, of nearly religious, unfathomable temperature.

Andy Warhol, and (1985–1986). Now live in Post-War & Contemporary Art on Artnet Auctions. Est. $120,000–$180,000.

O’Hara’s contemporary Andy Warhol also struggled with yearning so strongly ablaze that only the energy of chromatic distances immensely apart—but brought together on canvas—could evoke his as in O’Hara’s words “boundless love.” Warhol met Paramount executive Jon Gould in 1980, and both until and after Gould’s death, Warhol faced a piercing sharpness around his sometimes unrequited sexual desire: “Then the phone rang and it was Jon calling as if nothing had happened, as if he hadn’t gone away for the weekend and not called once,” he lamented in a diary entry from June 1981. Gould came down with pneumonia in 1984, at the onset of the AIDS crisis in New York; and historians have recently re-analyzed Warhol’s late-career, theological work as a response to the metropolitan emergency. Gould died of the illness in 1986, and it is perhaps not a stretch to read a temporal link between Gould’s passing and the black and white message in Warhol’s 1985–86 Mark of the Beast. So intense was his biblical reckoning with love and loss that it charged Warhol’s blood with a blinking pulse, visible in his graphic style burning with liquid polymer, ever closer “to the number of the beast: for it is the number of a man; and his number is Six hundred threescore and six” (Revelation 13:18).

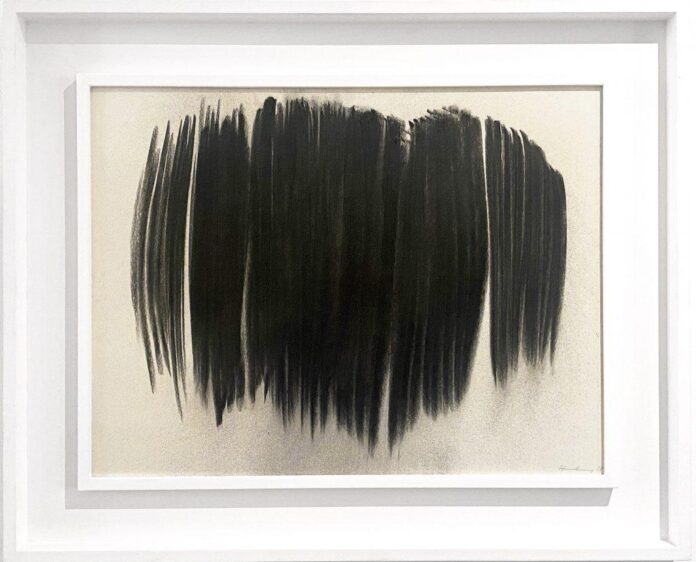

Adam Pendleton, (2019). Now live in Post-War & Contemporary Art on Artnet Auctions. Est. $150,000–$250,000.

The struggle to give form to a revised theology which reaches deep into the body, mixing shades of a candle flame’s hottest point and of its wick fleetingly extinguished, is a quest that persists in queer painting today. It is therefore little surprise that the artist Adam Pendleton’s pursuit of such spiritualism led him to enshrine the social and spiritual activist Ruby Sales in film. Sales, in 2016, expressed a necessity to touch what’s magnificent inside, at moments where we wonder where it hurts. Where Saint Serapion’s incandescent glow through shadow provided O’Hara with both a tomb for his love, and a path to depart toward freedom, “springing forth from it like the lotus—the ecstasy of always bursting forth!”—Pendleton’s syntactical sprays of black on white emit the brilliance of a love so boldly delicate, it can momentarily untether the soul from limitation; and through this achromatic makeup, his scalding passion flowers across pressing questions of identity in Untitled (Who We Are). Vertical stacks of thin chords stream downwards like a musical score flipped onto the infinite axis of a Christian cross, or a keyboard stretched to an emotive brink. The indecipherable pools of midnight cut from language, then layered forward, conjure Pendleton’s sense of a poetry so extraordinary it must in its physical core break from the world.

Raymond Pettibon, (1990). Now live in Post-War & Contemporary Art on Artnet Auctions. Est. $18,000–$24,000.

An incantation of life blossoming, yet rapidly and repeatedly incinerated, defines punk expression both sonically and visually—and Raymond Pettibon is an oracle for 1990s emblems of violently haunted love that shouts in black and white, perspiring with uncontrolled seduction. Pettibon manages to convey what his friends Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth portray about romance so precarious it might dissolve into a field of searing pain, at the unforeseeable speed of a car crash: “I cannot move, everything is about broken…pain, white light, blinded…some guy there kneeling in the blinded mirage of white light.” In Untitled (It goes without…) (1990), Pettibon turns to Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina to correspondingly reflect upon the type of “burning ember” that the band canonized. A man’s muscular back heroically kneels over as if he has momentarily emerged from “an agonizingly painful period of time” (In the Kingdom #19, 1986) which could perhaps compare to Count Vronsky’s; in pain late in the novel, he sees Karenina scarred as “a faded flower he has gathered, with difficulty recognizing in it the beauty for which he picked and ruined it.” In Pettibon’s distinctive hand, his Vronsky hotly emanates, knowing the shadowed power of his love’s extremes to inflict infernal, lustful doubt.