Paula Rego is a feminist artist whose totem chronicles of femininity touch on the many social taboos imposed on women. Her work is currently featured at this year’s Venice Biennale. The artist died at the age of 87.

London’s Victoria Miro Gallery, which represents the artist, confirmed the news on Wednesday. In a statement, the gallery named Paula Rego an artist of uncompromising vision who brought deep psychological insight and imaginative power to the figurative art genre.

In a career that spanned almost eight decades, Paula Rego explored the complexity of human relationships in terms of personal and political systems of power and control. Her most impressive work visualized women’s repressed agency, such as her series Abortions (1998–99), which presents the suffering of unsafe abortions in an unusual in Western art history frankness.

These figurative paintings and pastels depict women at various points during and after home abortions. The women often squat or lie down in severe pain. In some cases, women look directly at the viewer, as if admonishing him for his role in preventing safe and legal abortions.

This series of works was inspired by the slightly defeated referendum on the legalization of abortion in Portugal’s native Rego and is credited with helping to sway public opinion in favor of legalizing abortion in the second referendum in 2009.

“There were a lot of things that I would not talk about in real life, but in my paintings, I could do anything. Pictures are allowed. Such a relief. Anyway, no one came to arrest me,” she said in a book of interviews with Paula Rego conducted by other artists.

Artist Paula Rego was born in Lisbon in 1935. Her parents emigrated to England and left her in a women’s home run by a grandmother, an aunt, maids, and, according to her, a strict governess. It was a privileged, liberal upbringing.

At the age of 16, Paula Rego was sent to a finishing school in Kent. She later studied at the Slade School of Fine Arts in London when Lucian Freud was a teacher there.

Society in Portugal was repressive towards women (they did not get the right to vote until 1976). And Rego’s early work—collages of magazine and newspaper clippings and her own drawings—raged against the circumstances of women who weren’t born into her own socioeconomic class.

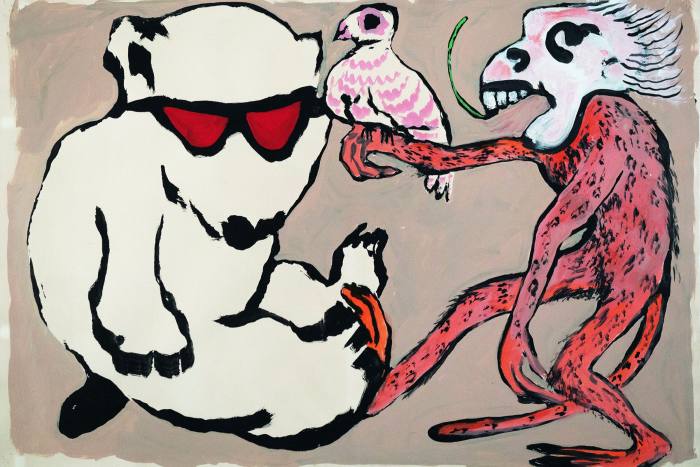

Her paintings began as semi-abstract, but over the course of her career, they lost their abstract character and became defiantly figurative, rooted in Jungian theory, where primal fears emerge with a fantastical twist.

In 2021, Tate Britain hosted a major retrospective of Rego’s work. In an interview before its discovery with her friend, the poet Alberto de Lacerda, Paula Rego called these early experiments an attempt to prevent the flight from the idea of high art.

Paula Rego said she drew inspiration from cartoons, newspaper reports, street events, proverbs, children’s songs, folk dances, nightmares, wishes, and fears. Women, animals, and puberty girls fill many of Rego’s canvases, which served as tools for working with her personal files.

For example, in the 1980s series Red Monkey, crudely drawn toy animals act as avatars for her husband’s extramarital affair, artist Victor Willing. In one of the scenes, Paula Rego cuts off the monkey’s tail with obvious pleasure.

Paula Rego was a tireless artist and had recently turned to sugary retellings of classic fairy tales and intimate family pictures. Her 2021 Tate Britain retrospective went to The Hague Art Museum in The Hague, Netherlands, and is currently on display at the Picasso Museum in Malaga, Spain. Her work is also currently featured in the Women Painting Women group exhibition at the Fort Worth Museum of Contemporary Art in Texas.

Her work is in the collections of many museums, including the British Museum, the National Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Last year, the artist fell, severely injuring her face. The Financial Times visited her London studio after she recovered and found that she had already turned the experience into art: her temporary deformity was captured in a series of rare self-portraits. Paula Rego enjoyed creating uncanny studio models and was photographed sitting next to a life-size mannequin that looked like her, but twisted like a faulty memory.

“I’m not trying to make things beautiful, that’s not particularly interesting,” Rego said, “and I expect I would find things beautiful that others find ugly.”