Kenneth Anger, the experimental filmmaker and author whose work galvanized avant-garde cinema, has died, reported his gallery, Sprüth Magers. He was 96.

“Kenneth was a trailblazer,” read a statement from the gallery, which began representing Anger in 2009. “His cinematic genius and influence will live on and continue to transform all those who encounter his films, words, and vision.”

Born Kenneth Wilbur Anglemyer in Santa Monica in 1927, Anger began creating 16mm films in his teens, marrying his burgeoning interests in underground cinema and the occult with his awakening sexuality. By the time he was 20, Anger had been brought to court on obscenity charges for his homoerotic short Fireworks (1947), receiving, along with his acquittal, a reputation as an enfant terrible.

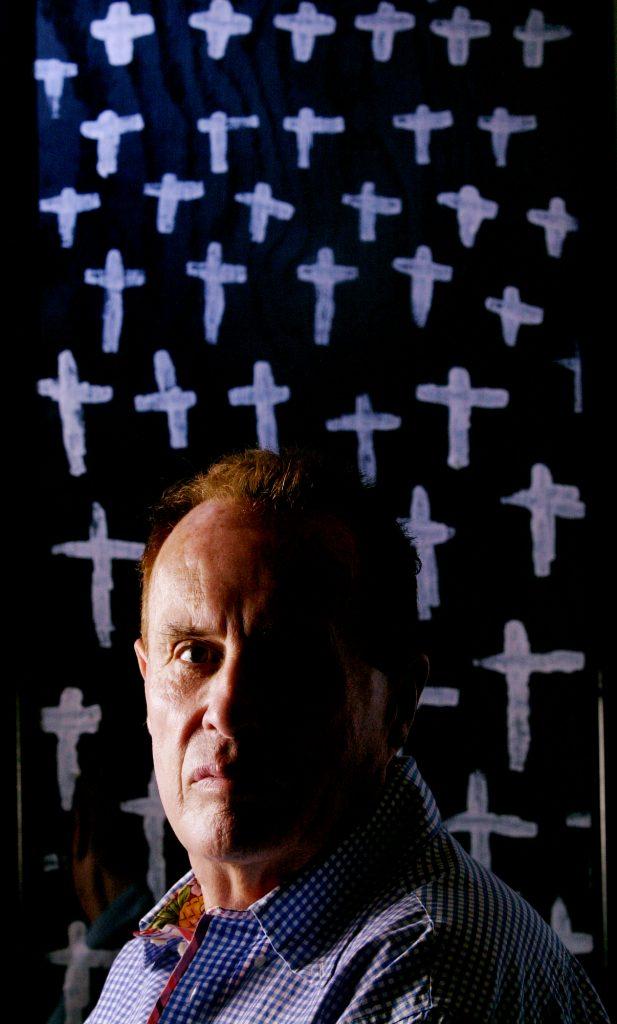

Kenneth Anger in Los Angeles, California, 1955. Photo: Estate of Edmund Teske/Getty Images.

It was a label that Anger proudly wore throughout his creative career in which he continued to bottle his devilish visions in films, especially those in his so-called Magick Lantern Cycle, that tested and torched the limits of mainstream propriety. “My dreams are big budget,” he said in 2014, “and my movies are small budget.”

Anger did brush up against Hollywood too—in his own way. His 1965 book, Hollywood Babylon, sordidly detailed (and sometimes made up) scandals that dogged the likes of Marilyn Monroe, Charlie Chaplin, and Jean Harlow. It was banned until its republication in 1975. Anger followed it up with Hollywood Babylon II in 1984 and teased a Hollywood Babylon III, which he claimed was on hold because he feared a lawsuit from Tom Cruise and the Church of Scientology.

Kenneth Anger’s (1954) at Art Basel, 2015. Photo: Michele Tantussi/Getty Images.

For an artist with a relatively small filmography, Anger left an outsized footprint on cult cinema and beyond. His works paired prismatic visuals with a pop soundtrack in ways that presaged the music video, while his queer narratives offered an enduring visual language for today’s pop culture. In the 21st century, Anger’s countercultural works have received recognition in the form of documentaries, DVD rereleases, and museum showcases, including a major retrospective at MoMA PS1 in 2009.

In tribute to the late iconoclast, here are six of his essential works.

Fireworks (1947)

The film on which Anger made his name saw him play a “dreamer” who is set upon by a group of sailors while out cruising—a premise inspired by a scene the filmmaker witnessed during the 1944 Zoot Suit Riots. Filmed in black-and-white and without sound, Fireworks encapsulated the homoeroticism, surrealism, and fearlessness that would inform his later work.

“It’s easy to be brazen when you’re 17,” he said in 2007, on the film’s 60th anniversary, “and know what you want to do and barely have the means to do it.”

Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954)

Anger’s occultism flowered in this film, which is light on plot but heavy in sumptuous, hallucinatory visuals. Loosely speaking, Pleasure Dome brings together a cast of mythical characters, from Pan to Aphrodite to Ascarte (played by a resplendent Anaïs Nin), who wind up in a bacchanal overseen by the Great Beast himself. Anger raided the closet of cast member Samson de Brier for the film’s eye-popping costumes, then availed himself of double exposure and quick cutting to build to its psychedelic climax.

Scorpio Rising (1963)

Perhaps Anger’s most influential work, Scorpio Rising depicts the violent hijinks of a motorcycle gang, but again, it’s the filmmaker’s stylistic choices that earned the short a spot in the National Film Registry. His romantic framing made a fetish out of leather and motorbikes, while his rock ‘n’ roll soundtrack made celebration out of rebellion. The latter was particularly inspiring to one Martin Scorsese, who said Scorpio Rising “gave me the idea to use whatever music I really needed.”

Invocation of My Demon Brother (1969)

From the late ’60s on, Anger’s output would increasingly reflect not just his deepening interest in dark magic, but the disillusionment of a post-Manson age, which also gave rise to the counterculture. Invocation embodies this shift, bringing to life a midnight mass (attended by Lucifer, played by Manson family member Bobby Beausoleil) with double exposures, giallo-esque lighting, and a downbeat soundtrack provided by Mick Jagger. Hypnotically edited, it also folds in found footage and Anger’s prized motifs, including Hell’s Angels and the eye of Horus.

Lucifer Rising (1972)

Anger’s long-gestated visual homage to Aleister Crowley’s poem Hymn to Lucifer is perhaps his most formally conventional work—recounting the summoning of the dark lord by Egyptian gods—not that it isn’t replete with his arcane symbolism. It also stars Marianne Faithfull, and was partially shot on-location in Egypt, for which Anger managed to get clearance by claiming he was “doing a documentary.” Today, the film is remembered for sparking the complex years-spanning feud between Anger and Beausoleil (who composed its soundtrack from jail) over footage that was supposedly either lost or stolen, depending on who you asked.

Don’t Smoke That Cigarette! (2000)

Lucifer Rising pretty much closed out Anger’s most creatively fertile period. He laid low for two decades, only releasing Hollywood Babylon II when he was in need of money, before he returned to filmmaking in 2000 with None of his esoteric hallmarks are here; instead, the work is a collage of cigarette commercials intended to tout the virtues of not smoking—an editing style Anger would adopt for his latter-day films, which were tepidly received. It’s a muted way to close out a transgressive career, but perhaps the last thing left to subvert were our expectations.