Paul Cézanne’s Still life (around 1890)

Courtesy of the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design. Photo: Børre Høstland/Jarre, Anne Hansteen

The French Wave

In her biography of Munch, Sue Prideaux describes the early collection of Oslo’s National Gallery as being “stuffed with a great many Flemish and Dutch also-rans”. That all changed thanks to Jens Thiis, its pioneering director in the first half of the 20th century. He acquired numerous French masterpieces, including a Van Gogh self-portrait and a Cézanne still life. Further works by Gauguin, Courbet and Delacroix were added. He toured Paris, buying works from Ambroise Vollard and Paul Durand-Ruel, and visited Renoir at home. The curator found the Impressionist in cantankerous mood, recalling that Renoir would have been unaware “that anyone up in distant Oslo, where polar bears, as is known, wander about the streets, dreamed of creating a collection of French art!”.

The Norwegian National Gallery, Oslo, in 1885

Photo: Olaf Martin Peder Væring/Oslo Museum

Founding the Norwegian National Gallery

The origins of the National Museum lie in the Royal Palace, which in the mid-19th century hosted the first incarnation of a public collection. The works were granted their own home in 1882, however, when a neoclassical gallery, designed by Heinrich Ernst and Adolf Schirmer, opened alongside the city’s university. Between 1904 and 1924, two wings were built to cope with the growing picture collection—including Munch’s The Scream and Madonna and further motifs from the painter’s Frieze of Life series as well as other fin-de-siècle Norwegian masterpieces by Johan Christian Dahl, Peder Balke and Harald Sohlberg. It continued to serve Norwegian art lovers for more than a century. Closed in 2019, in preparation for the opening of the new National Museum, the future of the much-loved gallery building remains uncertain. Reports that it could be turned into a hotel were met with public outrage, after which it was decided the site would remain under the aegis of the National Museum.

Inside the The National Museum – Architecture Børre Høstland / The National Museum

The Architecture Museum

Of around 90 rooms in the National Museum, only three are dedicated to single figures: Munch, of course, and the innovative naturalist Harriet Backer, while the third is Sverre Fehn (1924-2009), Norway’s key 20th-century architect. Appropriately, considering Fehn personifies the country’s architectural renaissance, in 2001 he was commissioned to design the National Museum – Architecture. He reconfigured a 19th-century branch of Norges Bank at Bankplassen 3—one of Norway’s first Empire Style structures—with a contemporary glass, concrete and oak pavilion. Fehn believed that Norwegian architecture would forever be entangled with the forces of nature. “The intellectual world meets the landscape, and in the ensuing duel, beauty is born,” he wrote. That battle is well documented in the museum’s collection of architectural plans, photography and models. The Bankplassen site will remain under the umbrella of the new National Museum, with its own exhibition programme along with activities surrounding the Oslo Architecture Triennale (23 September-29 January 2023).

An image from photographer Ivar Kvaal’s book 36 Pictures from the National Museum © Ivar Kvaal

Construction of the National Museum

While politicians and the public debated the design, location and size of the National Museum during its protracted build, Oslo photographer Ivar Kvaal found abstract potential in its temporary spaces. In his book 36 Pictures from the National Museum, Kvaal focuses on a series of empty rooms in flux: galleries half-formed, semi-rendered corridors, halls of building materials. The construction site provides a subdued palette, while Kvaal’s lens picks up the occasional dashes of colour: orange masking tape, blue paint pots. “It’s about setting a stage for your imagination,” Kvaal says. “All the tools and bits and bobs left that could be part of a play.” The book includes an essay by the museum’s architect, Klaus Schuwerk, who says that a museum should deliver a symphony of rooms to which the visitor should be both the player and the listener. Kvaal captures the silence before the show.

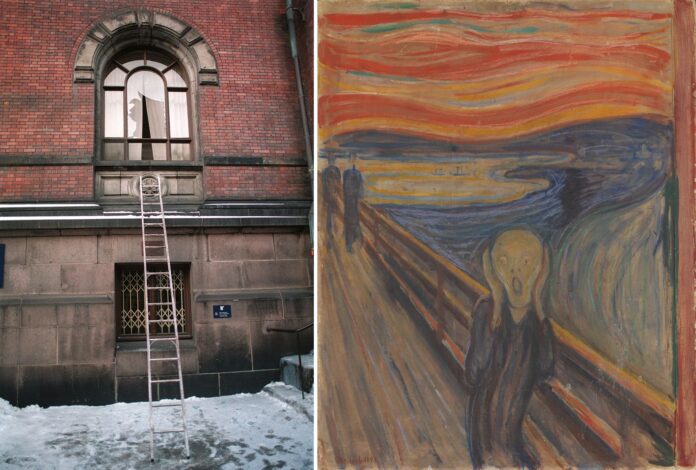

The ladder used by thieves to break into the old Norwegian National Gallery to steal Munch’s The Scream (right) Photo: Stig B. Hansen, NTB/SCANPIX

Theft of The Scream

The theft of Munch’s The Scream from Oslo’s National Gallery in 1994 was the most shocking art crime since the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre in 1911. In Oslo, it was an amateurish, but effective, smash and grab more than a high-concept Thomas Crown affair. On the snowy night of 12 February, while Norwegians were fixated on the opening of the Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, two men placed a ladder against the front wall of the gallery, broke a window, climbed in and simply took the painting off the wall. They left a note, which read: “Thanks for the poor security.” The picture was discovered three months later in a hotel in Åsgårdstrand (where Munch kept a summer house). In 1996, four men were convicted of its theft.

• Read more about Norway’s new National Museum here