When curators at the Art Institute of Chicago were putting together the museum’s first-ever show on Salvador Dalí, they grew worried that one of the works might not be the real deal. They set out to conduct painstaking research into the seven-foot-tall painting, (1936), acquired in 1987.

All that was known of its provenance was that it was a gift from the late museum trustee Joseph R. Shapiro, the founding president of Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art.

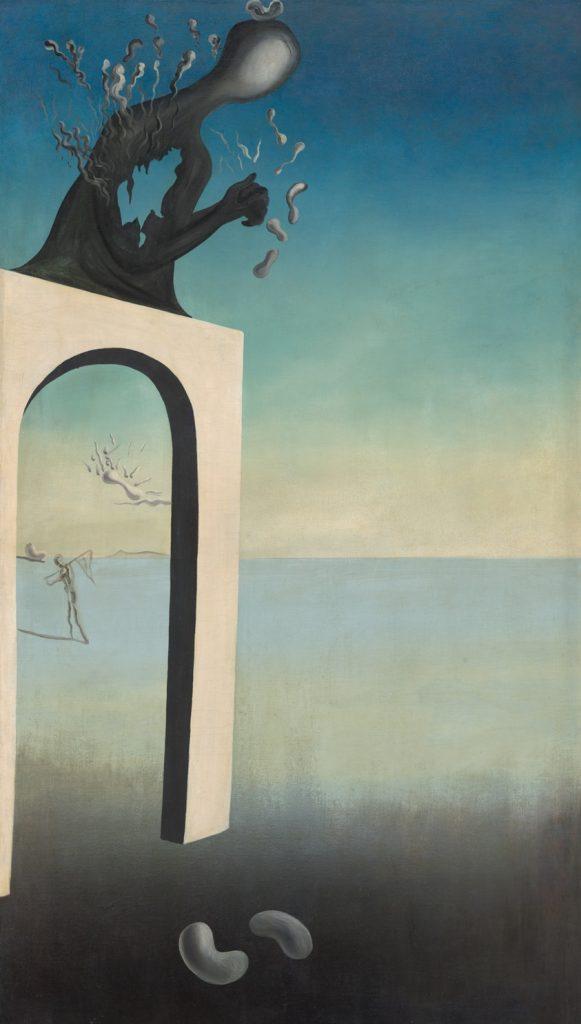

Curators Caitlin Haskell and Jennifer Cohen had spotted some possible red flags. The large vertical work, with its sparsely populated landscape was an outlier from the period, when Dalí was focusing on small-scale compositions of animals, objects, or individual figures with a proliferation of detail.

Also, the artist is known for recurring motifs, such as the famed melting clocks in his best-known work, 1931’s . The details in —a shadowy figure perched atop an archway with a gaping hole in its stomach, someone in the distance carrying a bindle, and three beans—seemed to be unique to this painting.

Salvador Dalí, (1939), detail. Collection of the Art Institute of Chciago, ©Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2018.

“We really couldn’t find anything like it across his work,” Cohen told CNN. “We were like, ‘Is this a Dalí?’ We were really panicking.”

Then she found a 1939 issue of with an article about Dalí’s controversial Surrealist pavilion at that year’s World’s Fair in New York. Accompany descriptions of the amusement park-like attraction, which featured topless mermaid performers dubbed “Living Liquid Ladies,” was an illustration the magazine had commissioned from the artist.

The drawing matched the small figure with the bindle in

Salvador Dalí, (1939), detail. Collection of the Art Institute of Chciago, ©Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2018.

That sent Haskell and Cohen to the archives of Dalí’s longtime dealer, Julien Levy, to find images of the pavilion. It turned out the artist had made a massive mural for the occasion, featuring melting clocks and other recurring imagery from Dalí’s oeuvre, such as burning giraffes. And on one end of the photo, partially obscured by decorations, appeared the mysterious painting.

Painting conservators Allison Langley and Katrina Rush examined the Art Institute’s work and determined that the canvas had been cut from the larger mural.

“It was a shock,” Cohen said.

As a result, the museum has rechristened the painting by its proper title, , and changed its date to 1939.

It is reunited in the current show with Dalí’s manifesto, “Declaration of the Independence of the Imagination and of the Rights of Man to His Own Madness,” which the artist wrote after the World’s Fair organizers rejected his plan to paint a version of Sandro Botticelli’s with a reverse mermaid—human legs, fish head—as its central figure.

Why the pavilion mural got cut up remains a mystery—as are the whereabouts of some of the other panels, though several are known to be in the collection of the Hiroshima Prefectural Museum in Japan. And no one knows how spent the years following the fair until Shapiro purchased it in 1966.

Salvador Dalí, (1936). Under infrared imaging, conservators spotted a portrait of King Ludwig II of Bavaria beneath the surface of the painting. Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, ©Salvador Dalí/Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí/Artists Rights Society.

The museum also conducted a technical analysis on 25 Dalí artworks ahead of the opening of the exhibition, which led to other revelations. (Titled “Salvador Dalí: The Image Disappears,” the show explores themes of visibility and disappearance in the artist’s work.)

Examining (1936) using x-ray and infrared imaging, conservators spotted what appeared to be a hidden graphite portrait of King Ludwig II of Bavaria, a patron of composer Richard Wagner, who appears in the finished painting.

Dalí may have intended the image as a kind of Easter egg. The curators have a similar theory about the hard-to-see dark blue dog in (1937). Conservators confirmed the artist intended for the figure to be almost invisible, suggesting the dog may have referenced Dalí’s friend Federico Garcia Lorca, who had recently been executed and had believed himself the subject of the 1929 film , written by Dalí and Luis Buñuel.

More Trending Stories:

Is Atlanta’s Art Scene Finally Achieving Critical Mass? There Are Big Signs That Point to ‘Yes’