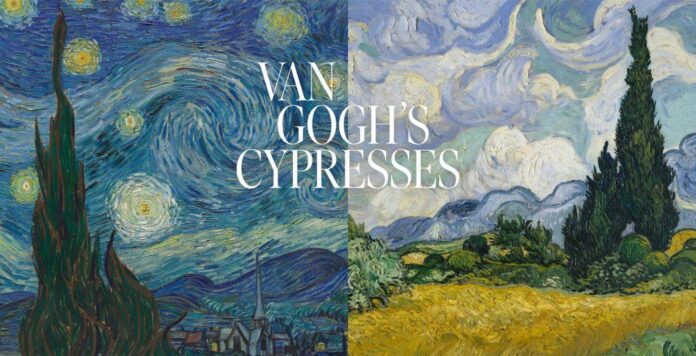

In celebration of the 170th anniversary of Vincent van Gogh’s birth, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art will present a deep dive into the Post-Impressionist artist’s depictions of towering cypress trees in the south of France—one of his most memorable subjects.

“It will be the first comprehensive show,” Met director Max Hollein said at a press breakfast offering a preview of the institution’s 2023 exhibitions, “to… exhibit and celebrate what might be the most famous trees in art history, these enormous trees of fierce power of expression that Van Gogh saw and then depicted in such a distinct way.”

An evergreen that lives for hundreds of years, the cypress became a fixture in Van Gogh’s oeuvre beginning with his move to Arles, France, in February 1888.

“In quick, confident succession, he fixed his sites on picturing the cypresses under star-strewn night skies and above windswept fields of golden wheat, later returning to his exuberant study from nature for a studio rendition,” Susan Alyson Stein, the Met’s curator of 19th-century European painting, said at the event. “Van Gogh’s inimitable cypresses have unfailingly captured our attention and awe.”

Vincent van Gogh, (1889). Photo © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The upcoming exhibition, titled “Van Gogh’s Cypresses,” will bring together no less than 40 of his drawings and paintings, as well as fascinating new details from technical studies conducted especially for the show.

From his first observations of the region, Van Gogh recognized the place that the trees would have in his work, writing to his brother Theo on April 9, 1888, that “I also need a starry night with Cypresses or—perhaps above a field of ripe wheat.” He later noted: “I’m astonished that no one has yet done them as I see them.”

Vincent van Gogh, (1889). Photo © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

“He didn’t bother to mention the obvious—that he’d of course seen the region’s celebrated evergreens, or [that] he was familiar enough with their age-old associations with death and immortality to invoke his tried and true metaphor for eternity and the eternal cycles of life,” Stein said.

“He simply pronounced, in ways both telling and prescient, his intention to bring his vision to bear on the cypresses,” she continued.

Vincent van Gogh, 1889. Photo courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum, New York.

The Met, of course, is home to , one of three versions of the 1889 composition the artist is believed to have painted (along with the even more famous ) during his stay at the Saint-Rémy mental asylum near Arles. (Van Gogh checked himself in after a mental break during which he cut off his left ear.)

“It’s one of the most celebrated paintings in our collection. It is not allowed to leave our premises due to the donor’s restriction,” Hollein said. “[So] an exhibition like this can only happen at the Met.”

Vincent van Gogh, (1889). Photo © The Museum of Modern Art, New York, licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York.

The show will reunite the Met’s with the original, version at London’s National Gallery (a third smaller version, which won’t be included, is in a private collection).

It will also feature a rare crosstown loan of , the gem of the Museum of Modern Art’s collection, marking the first time the works are on view together since 1901.

The Met will not, however, be addressing the allegations of James Ottar Grundvig from his 2016 book, . He argued that there is no evidence that Van Gogh painted a second large-scale version of the canvas in his studio, and that the Met’s copy is instead a fake by his friend, the artist and dealer Émile Schuffenecker, a known forger who is known to have owned the canvas.

Vincent van Gogh, (1889). Photo © The National Gallery, London.

“An enormous amount of evidence demonstrates that the painting is in fact by Vincent van Gogh,” the Met told the in 2016.

The book also noted that , purchased for $57 million by Walter Annenberg as a gift for the Met in 1993, came from the collection of Emil Bührle, a German arms manufacturer who made his fortune selling weapons to the Nazis.

More Trending Stories:

Click Here to See Our Latest Artnet Auctions, Live Now