In a tragic hit to global world heritage, vandals struck South Australia’s Koonalda Cave on on Nullarbor Plain, destroying 30,000-year-old artwork at the national heritage site. The cave is considered sacred by its owners, the Mirning people.

“This is quite frankly shocking,” South Australia Attorney-General and Aboriginal Affairs Minister, Kyam Maher, told Australia’s ABC Radio. “These caves are some of the earliest evidence of Aboriginal occupation of that part of the country.”

He called for a “severe penalty” for those responsible. Under the law, damaging an Aboriginal site could lead to six months jail time or a fine of A$10,000 ($6,700).

The cave is protected by a steel gate installed in the 1980s, but the vandals appear to have dug under it to break in. Due to national heritage laws and governmental bureaucracy, even the Mirning people need to get a key from the environment department in order to access the site, making it difficult for them to properly safeguard it.

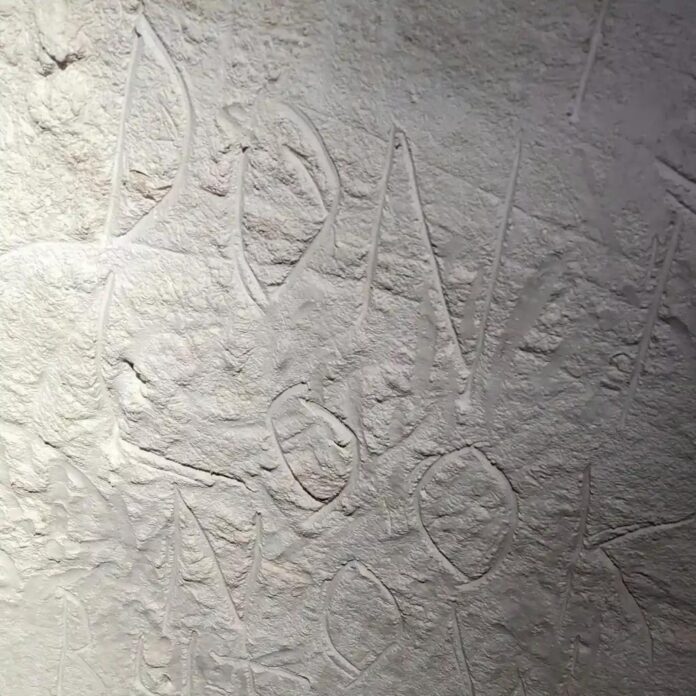

The ancient rock art is now obscured by graffiti, with messages like “don’t look now, but this is a death cave” scrawled across the age-old markings.

“The vandals caused a huge amount of damage. The art is not recoverable,” Keryn Walshe, an archaeologist of ancient Aboriginal sites, told the . “The surface of the cave is very soft. It is not possible to remove the graffiti without destroying the art underneath. It’s a massive, tragic loss to have it defaced to this degree.”

The incident follows the widely condemned leveling of 46,000-year-old Juukan Gorge rock shelters in May 2020. The CEO of Rio Tinto, the mining company responsible for the act, was forced to step down amid public outrage.

Australia’s indigenous activists have been outspoken in their efforts to prevent further damage to ancient petroglyphs caused by fossil fuel excavation.

At Koonalda Cave, the government and Mirning people had been in discussions since June over how to better protect it. The site had experienced other acts of vandalism over the years, with people sneaking in to carve their initials and the date on the rock walls, sometime using only their fingers.

“The failure to build an effective gate, or to make use of modern security services, such as wildlife monitoring cameras that operate 24/7, has in many ways allowed this vandalism to occur,” Clare Buswell, chair of the Australian Speleological Federation’s Conservation Commission, wrote to Aboriginal lands parliamentary standing committee in July, as reported by the .

The failure to respond to this call to action in a timely has now resulted in what appears to be irreparable damage.

“It’s abuse to our country and it’s abuse to our history,” Senior Mirning elder, Uncle Bunna Lawrie, told the BBC. “What’s gone is gone and we’re never going to get it back.”