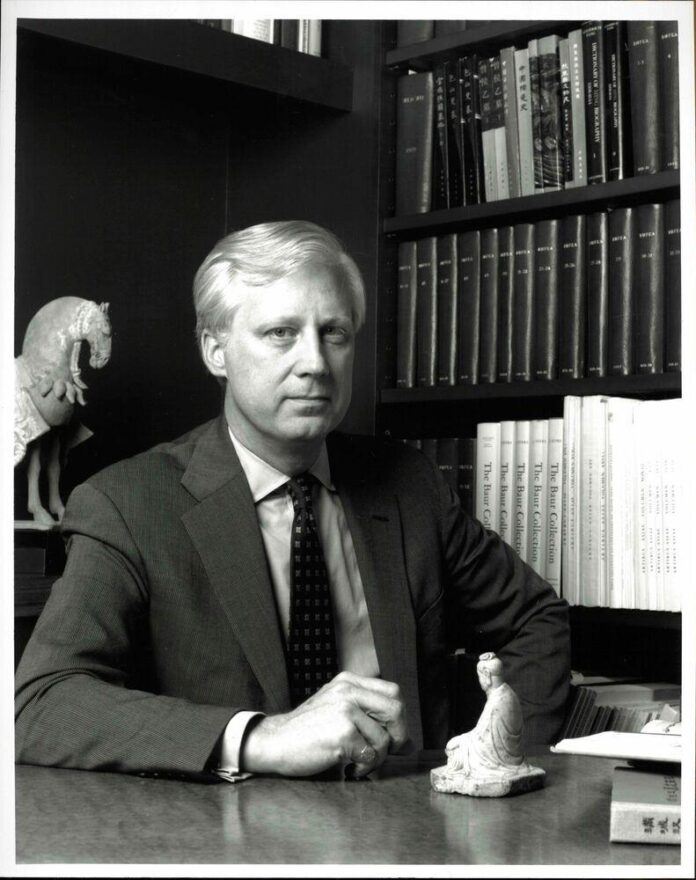

When the contents of James Lally’s renowned Chinese art gallery are offered at Christie’s in New York on 23 March, the retired dealer will not be in the auction room himself. That would be “bad form”, he says.

“I’m glad about this technical revolution; I can sit in the comfort of my home and follow the sale online,” Lally says. “You don’t want to get into the fray while everyone’s—hopefully—fighting over your things.”

The sale includes 138 lots of ceramics and other Chinese artefacts, some dating back as far as the Shang Dynasty (12th-11th century BC). Estimates for individual objects range from $3,000 to as high as $900,000 for a Guan bottle vase from the southern Song Dynasty (12th-13th century AD). Lally’s library will be offered in a separate online auction opening on 15 March.

A very rare Guan bottle vase from the Southern Song dynasty (12th-13th century) (est. $700,000-$900,000) Courtesy Christie’s

These are the residual trophies of a lifetime spent studying, buying and selling Chinese art, spanning an era of seismic change in the market. Lally left his post as president of Sotheby’s in North America to set up his New York gallery in 1986. He closed it 34 years later, in 2020.

He says he is “completely at ease” with the sale of his inventory.

Critical mass

“Time passes, and you’ve got to take a decision,” Lally says. “I’ve got a closet full of things I’ve been hoarding and a number of things that I’ve tried to sell and haven’t sold yet. Frankly, as a matter of practical marketing, a critical mass of good things available is what brings a crowd. In the middle of a career, you can’t just sell everything and start over again from scratch, so it’s something that only happens at the end.”

Lally says he has been fortunate to deal in Chinese art at a time when the market has opened to a wider world—and grown enormously. Art Basel and UBS’s annual art market report found that buyers from Greater China accounted for a fifth of global art sales in 2021, or $13.4bn. That was “unimaginable” when Lally started out more than 50 years ago, he says.

In the 1970s, the market for Chinese art was limited to a niche group of Japanese and Western collectors. “There were very rapid rises in prices throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and more and more Asian buyers, mainly from Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore. And then more mainland Chinese became active in the 1990s and 2000s,” he says.

“Now, there’s a steady trend of buyers from mainland China being the most active in almost every category.”

Local expertise

The market for Chinese art has benefited enormously from the local expertise of Chinese buyers, says Lally, who was renowned and valued by collectors for his scholarly approach.

“The catalogues done by the auction houses, just to take an example, used to be far less elaborate and far less detailed,” he says. “You look at the auction catalogues coming out these days, and they can be quite lavish—in the illustrations, the footnotes, the references. I think that’s all to the good.”

Hundred rib jab, Kangxi period (est. $400,00-$600,000)

Lally notes “xenophobic” tendencies in China’s current regime, which he describes as “not so hospitable to scholars” from outside the country. “But I don’t think the restrictions that Xi Jinping may or may not put on Chinese art will have much impact on the activity of buyers in the Far East,” he says. “That’s where the market leaders are.”

Dealers and auctioneers have been creative in finding new objects to fuel the market, Lally says. “Snuff bottles was more-or-less invented as a collecting category in the 1970s,” he says. Demand for painting and calligraphy has also increased dramatically since the arrival of Chinese buyers on the market, he adds.

One drawback is that US and European museums are often unable to compete with private collectors. “They don’t have a tradition of buying Chinese art at prices for six figures for a single object,” Lally says. “They don’t mind doing that for an Andy Warhol because they have been taught that’s what it’s worth.”

Finding inventory has often been a matter of chance. “No matter how hard you try, you just have to be in the right place at the right time,” Lally says. He fondly recalls the moment, not long after he opened his gallery, when a young man walked through the door with a Shang Dynasty gong—a bronze vessel shaped like a gravy boat—decorated with a dragon and tiger and in beautiful condition. It was, Lally says, “one of the most important objects I ever had in my hands.”

The young man said he had inherited it from his father and was not really interested in Chinese art himself. He wanted to buy a sailboat and wondered if the gong was valuable enough to pay for that. “I was very happy to tell him that it was valuable enough to buy two sailboats,” Lally says.

“These things are still popping up or sitting on someone’s mantelpiece right now waiting to be discovered,” he says. “There are always going to be surprises.”