Baltimore Art Museum (BMA), located in Baltimore, Maryland, USA, is an art museum founded in 1914. Today, the BMA houses more than 95,000 works of art, including the largest state holding. works of Henri Matisse. Highlights of the collection include a selection of American and European paintings, sculpture, and decorative art; works by contemporary artists; significant works of art from China; Antioch mosaics, and a collection of art from Africa. BMA’s galleries feature examples from a national collection of engravings, drawings, photographs, and textiles from around the world. The museum also has a 2.7 acre landscaped garden. The museum includes a 210,000 square foot building, which was built in 1929 in the architectural style of the “Roman Temple” designed by the famous American architect John Russell Pope. The museum is located between Charles Village, in the east, Remington, in the south, Hampden, in the west; and south of Roland Park, directly adjacent to the Johns Hopkins University Homewood campus, although the museum is an independent institution not affiliated with the university.

The highlight of the museum is a collection of cones collected by the Baltimore sisters, Dr. Claribel (1864-1929) and Etta Cohn (1870-1949). Experienced collectors and sisters have accumulated many works by artists such as Matisse, Picasso, Cezanne, Manet, Degas, Giambattista Pittoni, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Renoir, almost all of which were donated to the museum. The museum is also the permanent home of the George A. Lucas collection of 18,000 works of French art from the mid-19th century, which was recognized by the museum as a cultural “treasure” and “one of the largest collections of French art in the world”.

History

In February 1904, a major fire destroyed most of the central business district of Baltimore. In response, the municipal government established a city-wide congress to develop a master plan for the city’s reconstruction and its future growth and development. The Congress, headed by Dr. A.R.L. Duma, decided that the main drawback of the city is the lack of an art museum. This decision led to the creation of an 18-member committee for the art museum, which was chaired by art dealer and industrialist Henry H. Wiegand. Ten years later, the museum was officially included November 16, 1914. Along with Minneapolis and Cleveland, the Baltimore Museum was “modeled on two outstanding predecessors from the 1870s, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. According to a brochure published at the time of registration, Baltimore lags behind other cities “in terms of aesthetic interest.

Still, without a permanent residence, the young museum was founded with a single painting, “Sergeant Kendall’s Way,” donated by Dr. Dom himself. Since the founders of the museum were confident that more works of art would eventually be acquired, the nearby Peabody Institute agreed to keep the collection for a while until a permanent home was established. The committee began planning a permanent home for the museum collections.

In 1916, the building was bought on the southwest corner of North Charles and West Biddle Streets as a possible location for the museum. Although the architect was hired to reconstruct it, it was never occupied. By 1915, the group decided to locate the museum on a permanent basis in the area of Viman Park, west of the then Peabody Heights district (later Charles Village). By 1917, the group had received a promise from Johns Hopkins University to provide land south of the new Georgian Renaissance-style campus they were moving to. This alleged conspiracy was near the old 1800 Homewood Mansion and later the Italian-style Villa Wyman mansion of Hopkins’ donor and confidant, William Wyman, who had seen them leave the city center on North Howard Street and the Western Center they had occupied since 1876.

However, before finally moving into their permanent home in 1929, the museum was temporarily moved to the former home of their chief benefactor and founder, Mary Elizabeth Garrett (1857-1915), on 101st Street Monument, in the southwest corner with Cathedral Street (overlooking West Mount Vernon Place and the Washington Monument), in July 1922. Garrett, a famous philanthropist in his own right who also contributed to the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, was the only daughter of John Work Garrett (1820-1884), president of the Civil War in Baltimore and Ohio, a supporter of President Abraham Lincoln, and heir to the famous Robert Garrett banking firm in the city. In 1923, the museum opened its inaugural exhibition, which for the first week was attended by 6775 people. The house was offered to Ms. M. Carey as a home for “collections” and a meeting place for the Board of Trustees. Garrett’s old mansion was purchased in 1925 by a group of art enthusiasts who bought the property in order to preserve the museum intact. Despite the limited space, the museum offered rooms for art associations and a meeting room.

Meanwhile, in Wiman Park, the famous architect John Russell Pope (1874-1937) was designing the permanent house of the museum. During his years of study in Europe, the Pope is considered the main example of the classic revival style, which is so popular among traditional American architects. He is credited with a number of major buildings along the east coast of the United States and abroad, including the National Archives in Washington, DC, the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Tate Gallery Sculpture Hall in London. Its hallmark of classicism, both calm and monolithic, was perhaps the ideal choice for such an ambitious project.

The cornerstone was laid on October 20, 1927, in front of the future Art Museum Drive diagonally from North Charles Street. The system design for the original design of the building was completed by Henry Adams, a renowned local mechanical engineer. The building consists of three floors and includes several rooms that were reconstructed and/or replicated from six local historical houses in Maryland before they were lost or destroyed.

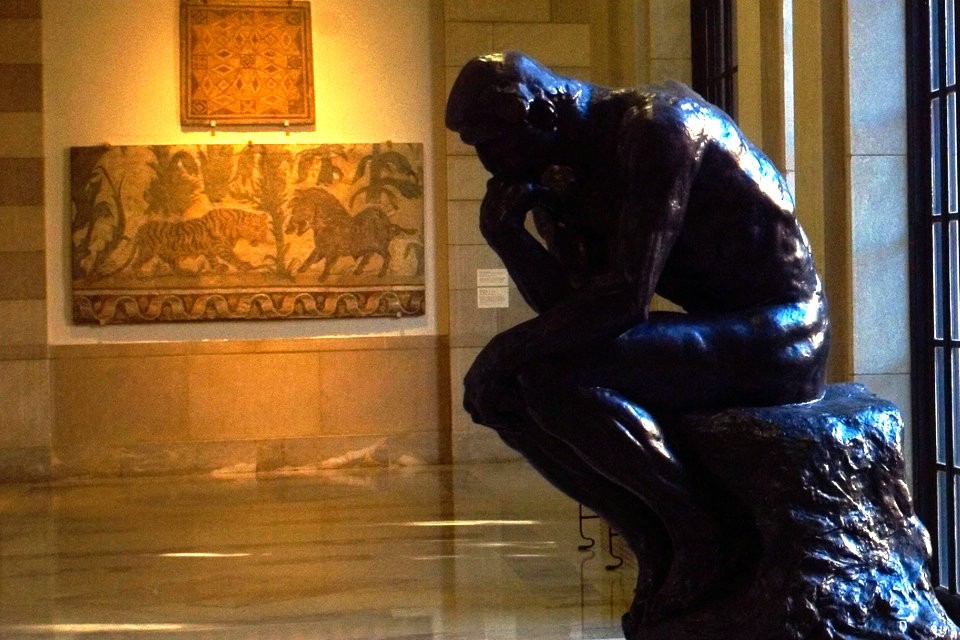

The construction phase was marked by controversy over its location, cost and quality, but on April 19, 1929, it opened on schedule without much pomp. The first visitors were welcomed by Rodin’s “Thinker” in Sculpture Yard, and most of the exhibits were provided by collectors from Baltimore and Maryland. During the first two months, the museum was visited by 584 visitors on average every day.

By the 1930s, the public reception was such that Director Roland McKinney wrote to Chairman Henry Treida: “People seem to feel that the Museum belongs to them and show that they are truly proud of it and its activities. Unfortunately, these people were mostly indigenous, privileged, and white, as noted in a 1937 report by Carnegie Corporation. “[Baltimore] cultural institutions (outside the library and schools) appealed to, were intended for, and were supported by a fairly small minority … they need to be open to the perspective of the whole community and its needs,” he concluded. Local artists also felt disadvantaged. “We, the living, the disgruntled, left to work in a vacuum of indifference and neglect while so many of the dead of the past are exhausted [BMA],” complained the president of the Baltimore Artists’ Union in the Evening Sun in 1937. The letter was written by Morris Louis, whose work will be in the BMA’s contemporary collection decades later. Trade responded to an extensive public survey and in 1939 presented the city’s first exhibition of African-American art. The show attracted over 12,000 visitors in two weeks.

Many of the items provided to the museum at its opening were eventually donated to it. Among the donors that formed the museum’s collection were Blanche Adler, Dr. Claribel Cohn and Etta Cohn, Jacob Epstein, Edward J. Gallagher, Jr. and Robert Garrett, Mary Frick Jacobs, Raida H. and Robert H. Levi, Sidi Adler May, Dorothy McIlwaine Scott, Elsie C. Woodward, Alan and Janet Würzburger. The growing collection is reflected in three major additions: the Saidie A. Wing. May in 1950, Woodward Wing in 1956 and Cone Wing in 1957. All these additions were designed by local architects Wrenn, Lewis and Jencks to match the original Pope’s building.

Today, the BMA collection includes over 95,000 objects, making it the largest art museum in Maryland. It is managed by a private board of trustees and receives funding from the City of Baltimore; Baltimore County, Carroll and Howard Counties; Maryland; various corporations and foundations; federal agencies; individual trustees; and many private citizens. BMA welcomes over 200,000 visitors annually. In addition to its collection of works of art, it organizes and organizes travelling exhibitions and serves as a major art center in the region as part of its programs.

Collections

African Art

BMA was one of the first museums in the United States to receive a collection of African art. Most of the collection was donated by Janet and Alan Würzburgers in 1954. It contains more than 2000 items, the sources of which range from ancient Egypt to modern Zimbabwe and includes works from many other cultures, including Bamana, Yoruba, Cuba, Ndebele. The collection includes many different kinds of art, including hats, masks, figures, royal staffs, textiles, jewelry, ceremonial weapons and pottery. Some of the works are known for their use in royal courts, performances and religious contexts, and many are known throughout the world.

The highlight of the collection are the works of woodcarvers Zlatan and Sonsanlvon, as well as the figures of the legendary brass master Laramie. Also on display are Lozi’s throne (ca. 1900), which is most likely carved at King Levanika’s court in western Zambia, a prayer board from the 20th century House of Horace, and a video work by Theo Aeshetou in 2006. At least a few masks and figurative sculptures are recognized worldwide as the best of their kind.

American Art

BMA has one of the best collections of American art in the world, with works spanning from the colonial era to the late 20th century. The exhibition includes paintings, sculptures, and decorative and applied art. The museum has several works of art from the Baltimore area, including portraits of Charles Wilson Peel, Rembrandt Peel, and other members of the Peel family; silver from Samuel Kirk & Son, a renowned silver company in Baltimore; a Baltimore album of quilted blankets; and painted furniture by John Finley and Hugh Finley of Baltimore.

The museum’s collection of American paintings ranges from 18th-century portraits and 19th-century landscape painting to American Impressionism and Modernism with works by John Singleton Copley and Thomas Sally, Famous paintings include “Wild Scene” (1831-1832) by Thomas Cole, “La Vachère” (1888) by Theodore Robinson and “Pink Tulip” (1926) by Georgia O’Keefe. They are complemented by a collection of engravings and drawings as well as contemporary photographs from the Gallagher/Dalseimer collection. Among the artists represented are Imogen Cunningham, Man Ray, Paul Strand and Alfred Stieglitz.

BMA has extensive experience in collecting works by African-American artists. It began in 1939 with one of the first exhibitions of African-American art in the country. This collection has grown considerably in recent years with the addition of more than 50 historical and contemporary works. Joshua Johnson, Jacob Lawrence, Edmonia Lewis, Horace Pippin and Henry Ossawa Tanner are among the African-American artists of the 19th and 20th centuries.

BMA’s American arts and crafts include an extensive collection of furniture that showcases major historic centers of carpentry in Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York and Boston. Many of these objects were received from Dorothy McIlwayne Scott, a generous Baltimore philanthropist and collector.

A gift made to Mrs. Miles White, Jr. in 1933, of more than 200 Maryland silver coins became the core of the silver collection, which now includes items from leading masters of the 18th and early 19th centuries in Annapolis and Baltimore, as well as examples of early English silver from Maryland families during the federal era. These include an Annapolis signature plate made by John Inche, a silversmith from Annapolis, and the oldest surviving silverware made in Maryland. Later masterpieces of the artists from Louis Comfort Tiffany to Georg Jensen can also be seen.

Other notable aspects of the Decorative Arts collection include a rare set of five flashlight windows and two mosaic architectural columns that represent Tiffany’s contribution to 20th-century decoration. The historic halls of six historic houses in Maryland, along with architectural elements from other historic buildings, illustrate urban and suburban styles from the 18th and 19th centuries, while a dozen miniature halls, made by Chicago miniaturist Eugene Cupjac, invite you to explore different decorative styles at close range.

Antioch mosaics

BMA presents a collection of Antioch mosaics, the result of its participation in the excavations of this ancient city, now known as Antakya in south-eastern Turkey, near the border with Syria.

With the support of BMA’s trustee Robert Garrett, the Baltimore Museum of Art joined the French National Museums, the Worcester Museum of Art and Princeton University during the excavations of 1932-1939, finding 300 mosaic sidewalks in and around the lost city. BMA received some of the mosaics from the excavations, a total of 34 sidewalks, 28 of which are on display in the museum’s sunlit atrium courtyard.

Found in the rich suburb of Daphne and the nearby port town of Seleucia Pieria, the mosaic dates back to the reign of Emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century AD and the Christian Empire Justinian in the 6th century, connecting the classical world and the early middle. Ages. The mosaics illustrate how the classical art of Greece and Rome evolved into the art of early Christianity, and describe how people lived in this ancient city before its destruction by the catastrophic earthquakes in 526 and 528 AD. The mosaics are distinguished by their grand scale and carefully designed borders, as well as the splendor of their decorative and naturalistic effects.

The Art of Ancient America

This collection contains works from 59 different artistic traditions of the Aztecs and Mayans of Mesoamerica, Chimu and Muisca of the Andean South America, Nicoya, and the Atlantic watershed of Costa Rica. The collection includes works from 2500 BC to 1521 AD. The main collection of 120 items was handed over to the Alan Würzburger Museum in 1958, which greatly expanded the existing collection and gave impetus to a travelling exhibition of Peruvian ceramics entitled “Myths of Ancient Peru (1969).

The collection is particularly fascinated by ceramics in Western Mexico, including an important model of the House of Nayarit and a throne leader. Also at the exhibition is a unique collection of 23 figures in dance regalia, which marks the ancient performance and emphasizes the diversity of art Colima.

Other notable works include a beautifully crafted snake figure of Olmec mastery, elegant depictions of Mayans and Aztecs demonstrating the integral role women played in the social, political, economic and spiritual spheres of society, and miniature gold rites in the Muija tradition.

Art of the Pacific Islands

This exhibition includes works of art from several cultural traditions of the Pacific Islands, including Melanesia and Polynesia. Works in the collection include jewelry, jewelry and tapas.

Of note are a finely carved dark wood lizard and shells from Easter Island; a battle bib created from hundreds of Nass shells that highlight Middy’s art in New Britain; and an 18th-century royal Hawaiian necklace.

Other highlights of the collection include a pectoral ornament decorated with small birds and stars that were considered a symbol of Tonga prestige on the Fiji Islands. Thanks to its ivory and pearl design, it is recognized as one of the largest of its kind.

Asian Art

The museum’s collection of Asian art includes works from China, Japan, India, Tibet, Southeast Asia and the Middle East. The collection is particularly known for its Chinese ceramics, with particular depth in Tang Dynasty funerary articles (618-907) and utilitarian ceramics from the 11th to 13th centuries. Despite the fact that this collection contains more than 1000 objects, due to limited space, only part of the exhibits is displayed simultaneously. The works can be seen in rotating installations in the Julia Levy Museum Gallery.

Some of the famous works in the collection include an early 15th-century life-size bronze Guanyin, commonly known as the “Goddess of Mercy”; a strong horse figure from a Han Dynasty tomb; a 39-seat dead retinue, a rare example of the number of clay figures that were placed in the tombs during the early Tang Dynasty; and an outstanding leaf-shaped washing machine, which represents the craftsmanship of Chinese blue and white porcelain. Asian art is also represented in other areas of the museum’s collection, including 475 Japanese engravings and 1000 fabrics from all over Asia.

European Art

The European collection of works of art in BMA contains works from the 15th to 19th century. Most of the collection was formed with donations from Baltimore’s private citizens, particularly Mary Frick Jacobs, George Lucas and Jacob Epstein. The collection contains a large selection of 19th-century French art, including more than 140 bronze animal sculptures by Antoine Louis Bari and several paintings by Barbizon artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Impressionist Camille Pissarro.

The collection includes a wide range of decorative arts and crafts, including snuffboxes, porcelain and silver. The museum also has a large collection of works on paper from the 15th to 19th century.

Highlights of the European art exhibition include Sir Anthony van Dyck Rinaldo and Armid (1629), which was commissioned by King Charles I of England. He is considered one of the best paintings of the artist. Other Nordic and French artworks include the portrait of Frans Hals, Dorothea Burke (1644), Rembrandt van Rijn’s painting of his son Titus (1660), and the image of Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin, depicting a beautiful girl throwing a ball in The Game of Knuckles (cf. (c. 1734), and the exotic Princess Anna Alexandrovna Golitsyna of the French court portraitist Louise Elizabeth Vigé Le Brun (c. 1797). Among the works of the Middle Ages and Renaissance are the Burgundy Mother of God with a 14th century baby, carved from limestone, and “Portrait of the Gentleman of Titian” (1561). There are also paintings of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance by Giovanni Dal Ponte, Biaggio D’Antonio, Sandro Botticelli and the Workshop, Bernardino Luini, Francesco Ubertini and the Master of Vision of St. Goudoul.

In 2012, Paysage Bords de Seine, Renoir, stolen from the museum, reappeared after being lost for 63 years. The painting then became the subject of a dramatic legal dispute involving the FBI, a woman who said she had found the painting, the rights of an insurance company to a work of art and the intentions of Sadie May, an art collector who bought the painting in Paris in 1925. and lent it to the Baltimore Museum. In 2014, a judge recognized it as the property of the museum after reviewing the relevant documentation from its archives. During the theft of Fireman’s Fund Insurance Co. paid the museum about $ 2500 for loss. The company decided whether to claim the painting when it came to the surface, but decided that it “belongs” to the museum.

Collection of cones

The Cone collection was the work of the Cone, Claribel and Etta Cone sisters, who in the early 20th century intended to purchase as many works as possible by artists such as Matisse and Picasso, as well as Cezanne, Gauguin and Van. Gauguin and Renoir are among other major artists of the era.

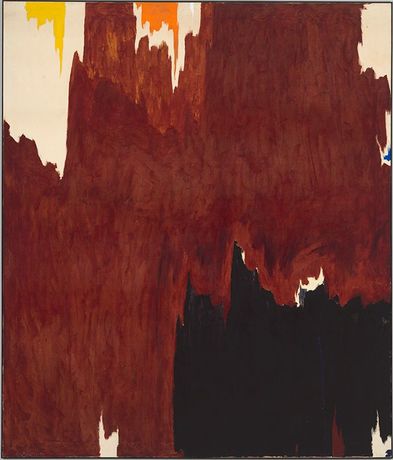

Contemporary Art

The modern BMA wing was built and opened in 1994, closed in January 2011 for renovation and reopened in November 2012 with new wall and floor finishes; a gallery dedicated to light, sound and moving images; a separate gallery for engravings, drawings and photographs; and BMA Go Mobile, a guide to the mobile website.

The recently restored wing also contains a two-part architectural intervention that made BMA the first museum in the United States to put into operation and purchase an installation for a specific area by artist Sarah Oppenheimer. It also features works by Olafur Eliasson, Jasper Jones, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Franz West, Yayoi Kusama, Donald Judd and other prominent artists, as well as new acquisitions of 21st century artists such as Gayton \ Walker, Josephine Mexeper, Sarah Sze and Rirkrit Tyranny.

It also features contemporary works by Oliver Herring, Philip Guston, Sarah Oppenheimer, Ed Rush and Olafur Eliasson. The works of the American artist Bruce Nauman, known for his work with neon lights, can be seen both in the modern collection and in the jewelry of the museum itself, as in the case of his work “Violins, violence, silence. The Baltimore Museum of Art has the second largest collection of works by Warhol in the United States.

The Baltimore Museum sold works by white male artists from its collection

The Art Museum in Baltimore has set itself the goal of making the art collection more diverse. For this purpose, in 2018, they auctioned seven works by famous artists of the twentieth century, including works by Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Franz Klein. By freeing up a place in the collection, the museum planned to replenish the collection with works by contemporary artists and artists of different races.

According to the census data, more than half of Baltimore residents are black (63.7% of the total). But the main art museum of the city shows mostly works of white masters. Museum director Christopher Bedford assures that he will do everything to correct this gap. According to him, this is a very important step, because “today the most important artists are African-Americans”.

Andy Warhol’s 1978 work in the Oxidation Painting series, dedicated to Jackson Pollock, was auctioned at Sotheby’s in May 2018. Also on display at the auction were “Green Cross” by Franz Kline (1956), “Bank Robbery” by Robert Rauschenberg (1979), “Azure Fox” (1963) and “Vital” (1982) by Kenneth Noland. The museum expected that the sales of these works will bring him $ 12 million. The Baltimore Museum sent the proceeds to its fund to finance art objects created after 1943 by women and artists of color. The museum’s Board of Trustees has already made a decision to purchase new works for the museum’s collection. Among them are paintings by Mark Bradford, John T. Scott, Jack Whitten, and Zanele Fly.

Baltimore Art Museum canceled the sale of its paintings at Sotheby’s two hours before the auction in October 2020

The decision was made after a private conversation between the museum management and the Association of Directors of Art Museums.

The Baltimore Art Museum (BMA) decided to suspend the sale of three works from its collection at Sotheby’s auction. The museum announced its decision just two hours before the auction in New York on October 28, 2020. The decision was made after a private conversation between the museum management and the Association of Art Museum Directors. Previously, BMA strongly advocated a plan to disassociate the works of Bryce Marden, Clifford Steele, and Andy Warhol (his 1986 Last Supper was valued at $40 million), despite protests that led to the resignation of two members of the museum’s board of directors. All in all, these works were supposed to bring the museum $65 million. The funds from the sale of the museum were going to be used for an action to diversify the funds of the museum, aimed at purchasing works by women and artists of color, which was called “Endowment for the Future. The disposition, the museum said, was fully in line with the new interim guidelines of the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), which allow for the sale of works if the funds go directly to “care of the collection. AAMD has already expressed its satisfaction with the museum’s decision to remove the works from sale: “We understand that it was a difficult decision, but we firmly believe it was the right one from our point of view: art collections should not be monetized except in very narrow and limited circumstances.