After Andy Warhol’s death in 1987, Velvet Underground founders Lou Reed and John Cale reunited for , a song cycle about their erstwhile benefactor. Performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, an album followed in 1990—an exemplary dedication.

It turns out this wasn’t Reed’s first batch of songs about his mentor. Reed (who died in 2013) recorded an unreleased cassette around 1975 based on the artist’s book . In a jaunty number that resembles a children’s song, Reed sings:

Another song wryly expands on Warhol’s “So what?” outlook on life. Discovered in 2019, these unreleased tracks can finally be heard—on headphones, at least—in a recently-opened exhibition at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, “Lou Reed: Caught Between the Twisted Stars.” Although they’re demos, as Reed said in 1973, “My shit is better than most people’s diamonds.”

It’s hard to impress a hardcore disciple, but mission accomplished with this show. “Caught Between the Twisted Stars” doesn’t compete (nor does it try to) with the mammoth “The Velvet Underground Experience,” which debuted at the Philharmonie de Paris in 2016 followed by a three-month East Village stint in 2019. And is there even much more to say about the band after last year’s superb Todd Haynes documentary? Rather, the exhibition (which opened on June 9) fleshes out Reed’s prolific yet oft-overshadowed solo career. It’s an intimate glimpse, not a completist vision.

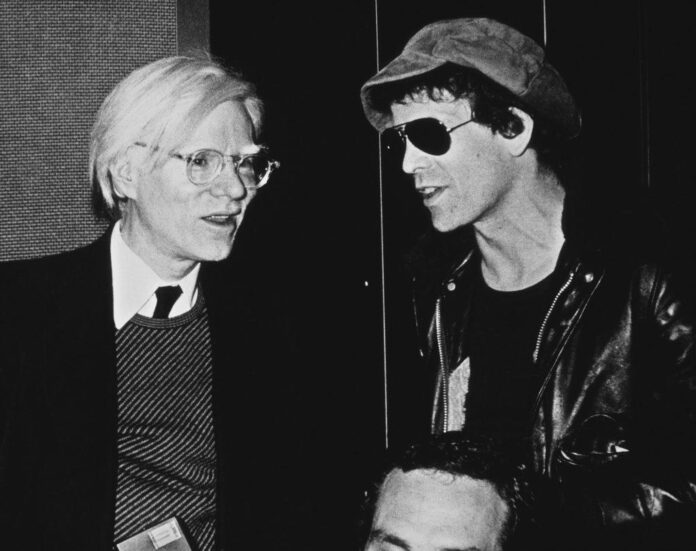

John Cale and Lou Reed of the Velvet Underground perform onstage at Cafe Bizarre, New York, December 1965. Photo: Adam Ritchie/Redferns.

Don Fleming and Jason Stern—who manned Reed’s archives until the cache was acquired by the New York Public Library in 2017—curated the exhibition, which draws from these holdings, plus the archives of Jim Carroll and the Sal Mercuri Velvet Underground Collection. The mighty trove includes include tour posters, studio notes, and assorted memorabilia. There is some of Reed’s personal correspondence, including birthday cards from VU drummer Maureen Tucker and a letter from another writer who, like Reed, specialized in tales of the disenfranchised and drug-addled, Hubert Selby, Jr. (he signed with his nickname, “Cubby.”) Over the years in photos, Reed morphs from a football jersey-wearing jock to glam-rock goblin androgyne and back again.

The photographer Mick Rock documented Reed in some of his most iconic images, such as the cover of his 1972 solo breakout, (both it and the follow-up, the devastating 1973 concept album, could have been better represented, but presumably the archives weren’t bursting with material from that period). Many of Rock’s lesser-known portraits of the musician appear here instead—outtakes from the cover session, Reed sitting in his apartment, flanked by his pet dachshund—and are more affecting than the images one has seen ad infinitum.

A compulsory detour into Reed’s mostly “meh” mullet-and-scooter era from the early 1980s is represented by items like the motorcycle helmet that adorns . A Betamax recording shows him energetically performing “Street Hassle” in 1978 wearing a midriff-exposing baby tee. The show excels in conjuring the magic of music-making through objects and artifacts.

Reed’s “Legendary Hearts” helmet and other memorabilia is on view. Photo: Max Touhey, courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The real treats, however, are the auditory gems, of which the Warhol-inspired tape is just one. A 1965 acoustic demo tape documents never-released forays and the gestation of seminal Velvets’ tracks- some years before their release. They include a countrified take on “Pale Blue Eyes” with backing accompaniment and vocals from Cale and a version of “Men of Good Fortune” that shares only a title with the eventual 1973 track. Light in the Attic, a reissue-specialty imprint, will release the 1965 tape in August as but a wealth of unreleased songs in the show are stuck in copyright limbo—such as the attempted piano ballad “Ondine,” by Reed, Cale, and Nico, from 1966. The tunes are worth the wait for the headphone stations and may inspire multiple visits—too bad you can’t skip to play what you want and must listen through.

He has had it: Lou Reed poses for an RCA publicity photo circa 1973 in New York City. Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images.

Reed’s wife, the artist Laurie Anderson, supplied items such as guitars, tai chi weapons, and the handwritten lyrics from 1974’s . The entire album is plotted out, as well as songs that didn’t make the cut, such as the intriguingly titled “Falling in Love 1 (Andy, Nico, John)” and “Falling in Love II (David, Angie, Iggy + Mick).” The pages have been assembled behind a wall of glass so one can see both sides. It’s perhaps the most moving visual component of the show, where ordinary meets sublime in the blue-inked germination of his work.