In September 2020, violence broke out once again between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh, a disputed region that has been the subject of conflict between the two nation states since 1988. Hostilities lasted for six weeks, resulting in an Azerbaijani victory. On 9 November 2020, a ceasefire agreement was signed which saw Armenia cede territories surrounding the Nagorno-Karabakh region to Azerbaijan.

In June 2021, The Art Newspaper published for the first time a tranche of declassified spy imagery taken by the US during the Cold War in the 1970s. An investigative report by Simon Maghakyan, the executive director of Save Armenian Monuments, examined the imagery in the nearby and similarly disputed border region of Nakhchivan, which, while officially autonomous, is under Azerbaijani control. Maghakyan’s analysis revealed that Armenian cultural heritage sites that have stood for centuries in Nakhchivan were at threat of “complete physical erasure”.

The war is ongoing, continuing to wreak havoc on the lives of those who call Nagorno-Karabakh their home. The conflict sporadically but persisently spills into violence, with more than 300 fatalities in September 2022 alone in the disputed region.

But something else is happening. The cultural erasure that Maghakyan tracked in Nakhchivan appears to be spreading to Nagorno-Karabakh as well. In October, Caucasus Heritage Watch (CHW), a US-based monitoring and research project from Cornell University, released the latest in a series of reports that compare and contrast contemporary satellite imagery of the region with images from the 1970s, 80s and 90s. The new report appears to empirically confirm Maghakyan’s fears: “To say that these sacred heritage sites are at risk might be a monumental understatement,” he wrote.

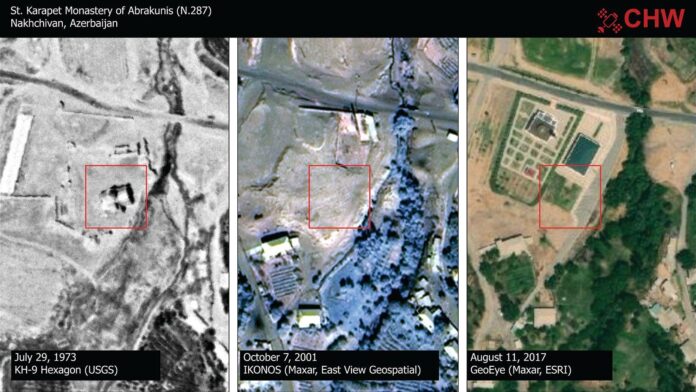

The CHW report is orientated around historical and contemporary satellite images that trace the ongoing destruction of Armenian cultural heritage sites, religious buildings and cemeteries in the region. Building on Maghakyan’s pioneering work, it details the Azerbaijani state-sponsored destruction of nearly all—98%—of Armenian heritage sites in Nakhchivan. The authors of the report fear that Armenian heritage sites in Nagorno-Karabakh, an area of around 4,000 sq. km, are at this moment facing the same fate as those in Nakhchivan.

Adam T. Smith, an archaeologist and professor of anthropology at Cornell University and a founder of CHW, started working in the Caucasus in 1992. “I have had a front-row seat for the way cultural heritage sites have been increasingly targeted as a part of this conflict,” he says. “As archaeologists, we speak for monuments that can’t speak for themselves.”

The CHW reports combine findings from technologies such as geographic information systems (GIS) and spatial data analysis with expertise in the human history of the region, research of pertinent academia and a host of on-the-ground sources and partners. “We’re not the first archaeologists to use satellite images to document this kind of destruction,” says Lori Khatchadourian, a professor of Near Eastern Studies at Cornell and a co-founder of CHW. “Technologies like GIS enable us to look at landscapes and conflict zones on a large scale and notice patterns of occupation over periods of time.”

Post-apocalyptic landscape

CHW’s report on Nakhchivan reveals “the complete destruction” of 108 Medieval and early modern Armenian monasteries, churches and cemeteries between 1997 and 2011. The report finds that there are only two Armenian sites remaining in Nakhchivan—the details of which the authors specifically leave obscure in order to protect them from harm. Of the destroyed sites, Smith and Khatchadourian point to several that are indicative of purposeful strategies of destruction.

The St. Hovhannes Church of Chahuk (built in the 12th or 13th century and renovated in the 17th and 19th centuries) was destroyed between 1997 and 2009, as documented in a new report from Caucasus Heritage Watch. Credit: Caucasus Heritage Watch

The church of Mijin Ankuzik in Nakhchivan, for example, had been in ruins for decades before being bulldozed at some point before 2009 (when satellite images show its obliteration). “The whole village is this post-apocalyptic, ruined landscape,” Khatchadourian says. “And yet the rest of the village is left untouched; the church is the only structure that has been razed.”

The report details how the Azerbaijani state particularly targeted Armenian cemeteries—an apparent attempt to wipe out the existence of Armenian families who have lived, died and were buried in the region. “Even the ghosts of the past have been eradicated,” Smith says. One of the cemeteries, the New Armenian Cemetery of Nakhchivan, was razed some time before 2005. “Satellite images show that a massive Azerbaijani flag monument was built exactly on the footprint of where the cemetery was,” says Khatchadourian. “This reappropriation was not accidental. It’s active, symbolic violence.”

Azerbaijan is largely a Muslim country, and the land on which other Armenian heritage sites once stood now hosts mosques and state-run civic buildings. A new mosque now sits on what was once the site of the St Tovma monastery of Agulis, described by CHW as “one of the most important religious centres in Medieval Armenia”.

“These Medieval monuments have a significance in both global and local archaeological history, and between 1997 and 2011, every Armenian monument was scrubbed from the archaeological record,” says Smith. “It’s a true cultural erasure.”

He adds: “This silent state policy is unlike anything we’ve seen before, and it can erase entire communities for centuries. We’re losing entire landscapes. It’s a remarkable tragedy of communities that have a history of living side by side for centuries but have been torn apart in the space of 30 years.”

Smith and Khatchadourian point out there is damage to Azerbaijani and Islamic cultural sites by Armenians in disputed territories as well—this will be the topic of an upcoming CHW report. But Khatchadourian says this appears to be more a “failure of stewardship” than a government-sponsored programme of cultural and historical erasure.

As for Nagorno-Karabakh, CHW is tracking more than 200 monasteries, churches, cemeteries and Armenian cultural sites, and a report is also forthcoming. The Azerbaijani government denies systematic destruction of Armenian heritage sites. “We’re inserting fact and real empirical data into a conflict that is rife with propaganda,” Smith says. “We can’t solve the conflict, but we can at least provide the facts.”