It’s been five years. Five long years since a painting found in New Orleans was sold at Christie’s New York for $450m as a lost masterpiece by Leonardo, possibly painted by the artist for a French king, and then, perhaps, owned by two English ones (more on this later).

Almost immediately after the sale of the Salvator Mundi, the buyer was revealed as the Saudi prince Mohammed bin Salman. We all know what happened next. Nothing. The most written-about painting of our time simply vanished from view and has not been seen publicly since.

There have been some tantalising promises along the way. First, the painting was supposed to go on loan to the Louvre Abu Dhabi who announced triumphantly on Twitter in December 2017 that “[we] are looking forward to displaying the Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci.” It never turned up.

Two years later, it was expected to be shown at the Louvre in Paris as part of the institution’s blockbuster Leonardo show. The museum even published, sold, and then withdrew, a special catalogue for it. But, once again, the painting failed to materialise.

We do now know that the Salvator Mundi was examined by Louvre specialists in Paris at their conservation lab in June 2018. And that the painting was seen in a Swiss Freeport, according to its restorer Dianne Modestini, when a Swiss expert was asked to inspect it in situ. News of both these sightings emerged obliquely, almost surreptitiously.

Of course, journalism abhors a vacuum, or perhaps, delights in one, depending on how you look at it, and, in the absence of any confirmed information about the painting’s whereabouts, hundreds of articles were published to fill the void, many of them in this newspaper.

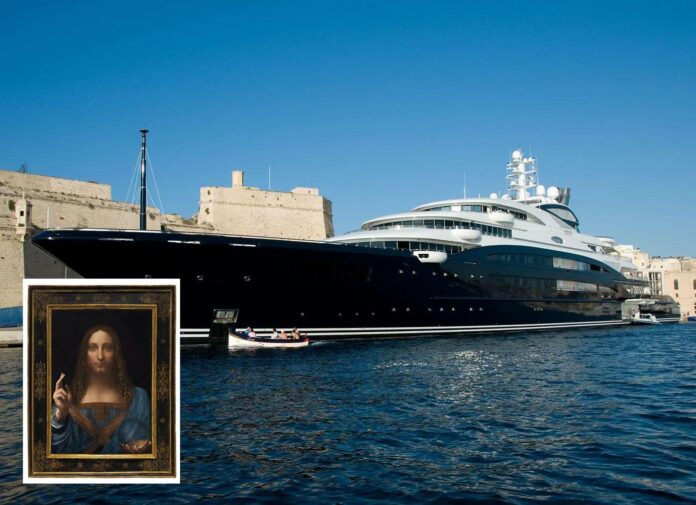

Perhaps the most captivating suggestion, first mooted by the collector and writer Kenny Schachter in June 2019, was that the Salvator Mundi was being kept on the Serene, a $400m superyacht owned by Mohammed bin Salman. Intrigued, this writer tracked said yacht for months. When it departed the warm waters of the Mediterranean for the North Sea and the Netherlands in October 2019, we speculated that the Serene might be delivering the Salvator Mundi to the Louvre in Paris for their Leonardo show. (It wasn’t.) A few helpful readers then pointed out that the Netherlands is where superyachts go for their annual maintenance. To which I say: fair point.

An equally plausible theory comes courtesy of our esteemed editor’s Uber driver who revealed to her one evening that a “very good friend” of his in France [occasionally] works for Mohammed bin Salman as an art adviser. According to him, the Salvator Mundi is now in the Saudi prince’s tasteful French chateau, modelled on Versailles, which includes such notable features as a meditation room in an aquarium.

Sure. Why not? I mean, if Christie’s can claim that their Salvator Mundi possibly belonged to English kings because royal inventories list a painting of Christ by Leonardo—their solid evidence for suggesting this is the very same work they sold for $450m seems to amount to: “wouldn’t it be great if it was?”—then surely our Uber driver’s testimony deserves to be added to the mix too. (Side note: my favourite Salvator Mundi story thus far has come from Ben Lewis, author of The Last Leonardo, who pointed out that there is a Salvator Mundi in Russia that actually has Charles I’s stamp on it…)

So, where is the painting now? Martin Kemp, Professor Emeritus of the History of Art at Oxford University, believes “it is in Saudi Arabia … the country is constructing an art gallery, which is to be finished in 2024,” according to a recent report in the Times.

Professor Kemp, who decries “lurid journalism” about the Salvator Mundi and the “monster egos” of those who dare to elaborate their own theories about the painting in a recent blog post, told the audience at the Cheltenham Literature Festival that “there have been moves to get me out to [Saudia Arabia] to look at the painting.” Of course, “the iniquities of the Saudi regime”, such as the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, the persecution of gay people and the Kingdom’s propensity to imprison activists, did give Professor Kemp pause for thought. “But if it helps to get Salvator Mundi out into the fresh air then I would be willing to do that.” To which we must all say: “Thanks Professor Kemp for your services to mankind.”

• Read all of our coverage on the Salvator Mundi here and read our special coverage on the five-year anniversary of the sale here

![The Art Angle Podcast: The Black Art Visionary Who Secretly Built the Morgan Library [Re-Air]](https://usaartnews.com/wp-content/uploads/SY17RQ1cexAJoKtoNDIw0ozh1H6AjfTnrDcjgU1m-80x60.jpg)