While sombre, unflinchingly detailed portraits dominate the oeuvre and market of Lucian Freud, the British artist was also adept at depicting the natural world—as evidenced by two works, painted at each end of his career, which will come to auction next month.

Scillionian Beachscape (1945-46, est £3.5m-£5.5m) and Garden from the Window (2002, £2.5m-£3.5m) have been held together since they entered the collection of the late Simon Sainsbury, one of the UK’s most prominent art philanthropists, who funded—among many things—a 1991 extension of the London National Gallery that is currently being redesigned. They have been consigned to Christie’s by the descendants of Sainsbury’s heirs.

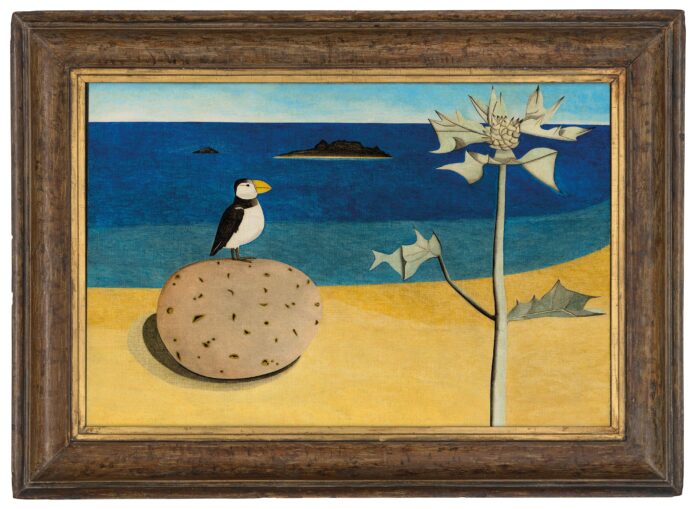

The beachscape, which depicts a scene in the Scilly Isles off the Cornish coast, was executed when Freud was 23 (his very earliest works date to when he was around 15, but these are not easily recognisable to non-experts). It was made while Freud was on a long summer holiday with his then-friend, the British painter John Craxton—a period during which Freud “made some of his most limpid and luminous paintings”, Craxton would later write. The pair celebrated the end of the Second World War by embarking on a series of travels that began in Cornwall, where they visited Barbara Hepworth, and some months later would see them make their way to Crete—a Greek island that Craxton would eventually move to and become closely associated with. Prominent works by Freud during this period include a portrait of Craxton, sporting a moustache and sunburn, and Head of a Greek Man (1946), which was sold at Christie’s in 2012 for £3.4m (with fees).

Craxton’s drawing of Lucian Freud made on 26 October 1946

The relationship between Freud and Craxton, who shared a St John’s Wood flat during the Blitz, was marked by an “obsessive” closeness and friendly professional rivalry that eventually gave way to bitter disputes as the former gained in fame and the latter saw his own career languish. A recent biography on Craxton details the promiscuous party days of the pair, their beginnings as young artists and studio mates, and the ways in which they helped develop each other’s practice. They “became so interwoven that it was unclear whose art was being influenced and how”, the biography’s author, Ian Collins, told The Art Newspaper in an interview last year.

Further scrutiny on their relationship has been spurred by the recent publication of Freud’s letters and personal notes, in which he writes to Craxton in a “private language” of nonsensical poems and codewords, and refers to him by affectionate and unusual nicknames such as “Mon Chere Spagonee” and “Cragzpino”, revealing a lesser-known side to the famously reticent artist. Biographers and historians remain undecided as to whether Freud and Craxton’s relationship was anything other than platonic; both frequently engaged in sexual and romantic relationships with men, as well as with women.

Lucian Freud’s Scillionian Beachscape (1945-46)

Courtesy of Christie’s

The second painting offered by Christie’s comes from a less exuberant period of Freud’s life, and is part of a series made in the artist’s final decade, depicting his overgrown garden at 138 Kensington Church Street in London. It was exhibited at Tate Britain in 2004, two years after it was painted. Freud’s somewhat overlooked relationship with plants and gardens is the subject of an exhibition at the Garden Museum in London (until 23 March), which opened as part of the ongoing celebrations to mark the artist’s centenary last year.

“It’s perhaps more accurate to think of Freud as a naturalist rather than a portraitist—his eye observed all sorts of surroundings in the same exacting way, says Tessa Lord, Christie’s acting head of postwar and contemporary art, London. She describes Freud’s market as relatively “guarded” compared to some other 20th-century titans and notes that works by the artist from before 1960 are not frequent seen at auction, with just eight having been sold in the past nine years. Lord adds that while the estimates of both works are far less than Freud’s $86m auction record, set by Christie’s at the Paul G. Allen sale last year, they are priced in line with the depictions of similar subjects, including the artist’s highest price for a garden scene, which Christie’s achieved in 2019 for $5.9m.