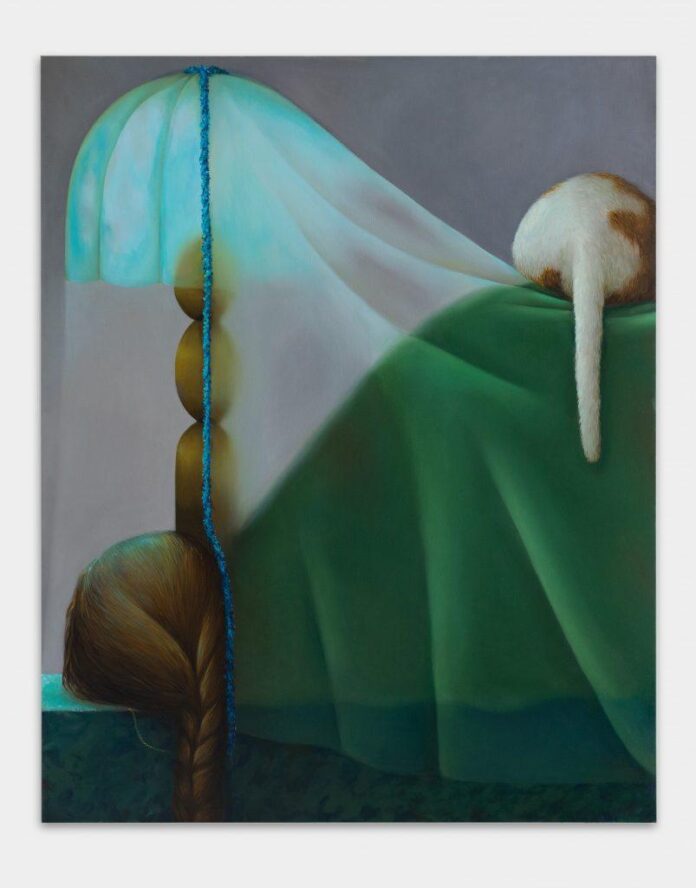

Time holds its breath in Diane Dal-Pra’s paintings. Women, still and silent as the décor around them, are seen from the back, revealing only their braided twists of long hair. One woman has laid her head in–or maybe behind—a fish tank. We can’t quite tell. Another has stuck her head inside a glowing lampshade. In yet another, Dal-Pra pictures a seated woman from above, who has planted her face flat against a tabletop. White lace is carefully draped over the crown of her braided chignon, like an oppressive wedding veil. Sylvia Plath’s head in an oven comes to mind, as does a kind of letting go or surrender.

Yet Dal-Pra’s works don’t portray any specific narrative. Instead, these sturdy, broad-shouldered women, whose bodies she zooms in on elements of, give a sense of quiet brewing, internal struggle, as well as the physical impulse to take refuge, as a means of coping. The artist’s often depicted furnishings and textiles can similarly hold life below their surface. Upon closer inspection, patterns on a rug, or cloth reveal women’s bodies in active movement or on all fours. A fly’s fragile silhouette, too, might appear on the inside of a lamp shade, before falling to join a pile of dead comrades below.

Installation view “Remaining Parts” 2022. Courtesy of Galerie Derouillon.

The French painter (b. 1991) draws from her dreams and distorted memories to construct her large oil paintings, which, like dreams, leave us with unexplained, overall impressions, that don’t quite make logical sense. Set within intimate, lamp-lit interior scenes of domestic daily life, these works verge on magical realism. Lending to that sense is Dal-Pra’s skill at painting suspended moments between states: she paints the air in a room, heavy with moisture, translucent gauze fabrics hung over faces, or water droplets about to fall from a drooping braid.

“I really like this tension that exists between things that are about to fall or spring up so that it creates a relationship to time, in which time has already done its work,” said Dal-Pra from her northern Paris studio. “That taut moment right before the denouement, when something else will happen, but everything is still possible, and nothing has been decided yet—that’s the moment that gives the most adrenaline, the most possibilities,” she said.

For Dal-Pra, too, it seems that anything is possible at this moment. The artist had her first solo gallery exhibition in 2020 and has already captured the imaginations of a cohort of international institutions and collectors. Her work titled “Slow cold fire” is currently included in LGDR’s “Rear View,” the inaugural group exhibition for the gallery’s New York flagship where she is shown alongside modern masters including Félix Vallotton, René Magritte (with whom she is sometimes compared), Francis Bacon, as well as contemporaries including Seth Becker, Francesco Clemente and Urs Fischer.

This exhibition marks an important career step for the rising artist, coming on the heels of critically acclaimed presentations with Massimo de Carlo in London in 2021, and with Galerie Derouillon during Paris + by Art Basel in 2022 (she is represented by both galleries). Both of these exhibitions led to institutional acquisitions by the likes of the Louis Vuitton Foundation (Paris), Yuz Museum Shanghai, and the Institute of Contemporary Art Miami, among others.

Diane Dal-Pra, The Other Room (2021). Courtesy of Massimo De Carlo.

“Our main concern is in placing Diane’s work in institutional collections so that she can have greater visibility,” said Marion Coindeau, director at Galerie Derouillon. Demand for Dal-Pra’s paintings, coupled with the slowness with which she produces work, has translated into long wait times for paintings now ranging between $50,000 and $140,000, according to her galleries.

“She takes forever to make a painting, and that’s part of their beauty because she works on the same detail for days,” said Ludovica Barbieri, partner at Massimo de Carlo. “She has a long career ahead of her,” she added, noting: “They really love her work in Asia too. But the fact is, we don’t have enough paintings for all the requests.”

When we met with Dal-Pra, she was busy working on her work for the LGDR show as well as several others slated for an upcoming solo exhibition at the Mostyn, a public art gallery in North Wales, in July. “It’s interesting for me to construct a series of paintings over a longer period, and to pass from one painting to another, so they evolve together. I find it more coherent,” she said of her slower method. These recent works draw from literature, photography, and film— particularly in their compositional framing—as well as the Renaissance.

“It’s as if time retracts, and I have a completely different relationship to time’s passing,” she said. “The act of painting is so all-encompassing which is why I love it. It involves the whole body, our attention and being.”

Dal-Pra’s paintings can have a similarly all-involving effect. Her works “call upon all the senses, including our sense of touch,” said Coindeau, “There is a lot of texture [in the recurring representations of fabric], and sound, even. The atmospheres [of the paintings] are very bundled up and muffled, giving the impression of a reigning silence.” In these paintings women often appear wrapped under thick covers, their heads resting on a pillow, or covered by fabric. Such works draw from Dal-Pra’s own battles with insomnia and the semi-conscious state she associates with it.

Diane Dal-Pra, (2021). Courtesy of Massimo de Carlo.

“The whole challenge is to create sensorial atmospheres that are not visual at all,” Dal-Pra explained. For her latest series, this atmosphere was achieved through “an evolution towards fewer elements, a paring down, but with more weight,” in the subjects, she said. While female bodies can still be larger than life, increasingly “they’re only suggested by a gestural, floating presence, as if they are dissipating, and the objects are becoming all that’s left of our mark on things,” she said.

Other works have no human presence and might portray draped or tied fabric on wooden, carved furniture and bedframes. These inanimate materials seem to hum and swell as if living protagonists themselves.

Dal-Pra can be superstitious about objects in her daily life, to which she attributes larger meaning. This resonates in her subjects, as with the long, braided, and bundled twists of hair she often portrays. Years after losing her mother at the age of 17, the artist came across her mother’s hairbrush, with strands of hair wound between its teeth. “I only saw the connection recently, but objects took on a completely different meaning after her death, and it was pretty incredible to tell myself that her hair was the only thing that was left,” she said.

Her mother also manifests, the artist says, in her “need to tell stories related to women.”

Dal-Pra wasn’t born into an artistically inclined family, per se. Her mother worked in pharmaceutics and her father in construction. But still, she doesn’t remember a time when she didn’t have a pencil or crayon in her hand. In college, Dal-Pra didn’t pursue fine arts, instead studying both art history and the applied arts. She had just begun working as an art director in Bordeaux four years ago when she abruptly quit and began painting.

“There are things that we can’t let pass us by,” she said of her decision to move to Paris to become a painter. “I didn’t want painting to just be my Sunday hobby – that wasn’t possible,” she said.

In 2019, she won the Artists’ Collecting Society’s Laureate prize that landed her a residency at Palazzo Monti, in Italy. Soon after, independent artistic director Nicolas Poillot connected her with Galerie Derouillon. “We really felt there was potential, and it was the beginning of something,” said Coindeau of the first studio visit with Dal-Pra and gallery founder Benjamin Derouillon. She was offered a 2020 Paris show, curated by Poillot, which set the relationship in motion.

As for Massimo de Carlo, Barbieri said she discovered Dal-Pra’s work on Instagram during the pandemic. “I didn’t know anything about the artist. Totally out of the blue, I saw an image and I loved it,” she said. Barbieri purchased one of Dal-Pra’s paintings through Derouillon—though she had to wait nine months to see it in person, due to pandemic restrictions.

Not having gone the traditional art school route, Dal-Pra concedes that a bit of “imposture syndrome” may be driving at least some of her highly technical, realist experiments with oil paint. “I love challenging myself to paint transparency. It’s exciting to figure out how to get it right,” she said. Dal-Pra’s signature, translucent surfaces are indeed a skillful wonder. She sometimes works with an iPad as a compositional tool. She photographs her paintings while in progress, testing the effects of changing light and composition on the digital image of the work, before continuing on with her painting. The reason, she explained, is because of her slow painting process in oil, which is not forgiving of experimentation directly on the canvas.

At her studio, Dal-Pra had recently worked on painting a fogged pane of glass, as though in a steamy bathroom, with a figure behind it. On it, was a quick, gestural form as though doodled on the wet surface by a finger. This had been her first attempt at the subject, and she pulled it off with uncanny talent.

“The hard part is finding just the right touch, knowing when to stop and not go too far,” Dal-Pra said, lest the glass, and its moist translucence, become impenetrable.