Was Leonardo da Vinci’s mother a slave from Asia?

That’s the theory posited by a new novel, which draws on deep academic research to fill in the many gaps in the historical account of the woman, simply known as Caterina. The book may just shake up generations of scholarship around the Mona Lisa‘s maker.

Il Sorriso di Caterina—or Caterina’s Smile—is the name of the novel, authored by the historian and University of Naples professor Carlo Vecce. It recounts, through a combination of fact and imaginative fiction, the story of how Caterina was kidnapped from the Caucasus area of Central Asia and moved to Florence, then Vinci, as a slave.

It was in the latter location that da Vinci’s father, a wealthy notary by the name of Piero da Vinci, supposedly freed Caterina—but not before she gave birth to a son out of wedlock.

“Their son was called Leonardo,” Vecce told the Associated French Press in Florence this week, following a preview of his book.

Journalists take pictures during the press conference for the presentation of Carlo Vecce’s book, Il Sorriso di Caterina (Caterina’s Smile) in Florence on March 14, 2023. Photo: Marco Bertorello/AFP via Getty Images.

Undergirding Vecce’s theory is a newly uncovered legal document, written in the fall of 1452, which recounts the emancipation of an enslaved Circassian woman named Caterina. Vecce, who discovered the document in the State Archives of Florence, believes it was penned by da Vinci’s father.

It was written by “the man who loved Caterina when she was still a slave, who gave her this child named Leonardo and [was] also the person who helped to free her,” the author explained, noting that other pieces of evidence similarly corroborate the connection between Caterina and the elder da Vinci. Vecce added that he’s also working on a scholarly article about his theory.

If his assertion is true, it would effectively negate previous theories about the identity of da Vinci’s mother, including suggestions that she was an orphan or a Tuscan peasant named Caterina di Meo Lippi. It would also mean that Italy’s most famous artist was, in fact, just half-Italian.

“When I saw that document I couldn’t believe my eyes,” Vecce added for NBC News. “I never gave much credit to the theory that she was a slave from abroad. So, I spent months trying to prove that the Caterina in that notary act was not Leonardo’s mother, but in the end all the documents I found went into that direction, and I surrendered to the evidence.”

“At the time many slaves were named Caterina, but this was the only liberation act of a slave named Caterina Ser Piero wrote in all his long career,” he went on. “Moreover, the document is full of small mistakes and oversights, a sign that perhaps he was nervous when he drafted it, because getting someone else’s slave pregnant was a crime.”

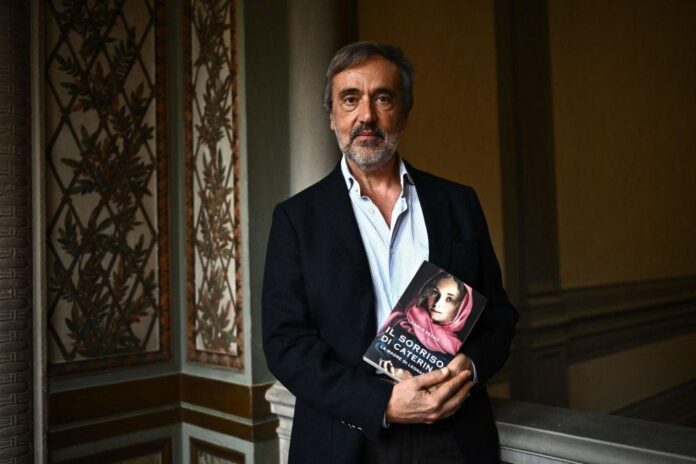

Carlo Vecce’sIl Sorriso di Caterina(Caterina’s Smile). Photo: Marco Bertorello/AFP via Getty Images.

Still, there’s a long way to go before Vecci’s idea is accepted by the small, competitive community of da Vinci experts.

“Carlo Vecce is a fine scholar. His ‘fictionalized’ account needs the sensation of a slave mother,” said Martin Kemp, a former University of Oxford professor who postulated the “Caterina di Meo Lippi” theory in a 2017 book. “I still favor our ‘rural’ mother, who is a better fit, not least as the future wife of a local ‘farmer.”

“But an unremarkable story does not match the popular need for a sensational story in tune with the current obsession with slavery,” Kemp added.

If there’s anything on which these and other da Vinci scholars can agree, it’s that, regardless of who his mother was, Leonardo was lucky to have been born out of wedlock.

“Otherwise, he would have been expected to become a notary, like the firstborn legitimate sons in his family stretching back at least five generations,” the author Walter Isaacson wrote in his 2017 biography of the artist, per the .

More Trending Stories: