Maya Widmaier Picasso, the eldest daughter of Pablo Picasso, died on Tuesday 20 December in Paris, aged 87, from pulmonary complications. The news was confirmed by her son, the actor Olivier Widmaier Picasso. He tells The Art Newspaper that she “died peacefully, surrounded by her family”, including himself, his sister the art historian Diana Widmaier Picasso and their father Pierre Widmaier.

The Picasso Museum in Paris is currently showing two exhibitions, curated by Diana, which are dedicated to Maya’s life and collection and which run until the end of the month. The first presents the works Maya offered last year to the French state as a “payment in lieu” for inheritance tax. She had selected six paintings, a sculpture, a sketchbook and a tribal statue, to complete the huge collection which founded the Musée Picasso after her father’s death in 1973. “She was very attached to the idea that her inheritance should go to a museum,” Olivier says, “so I always thought I had a ‘little brother’ called the French public collection.”

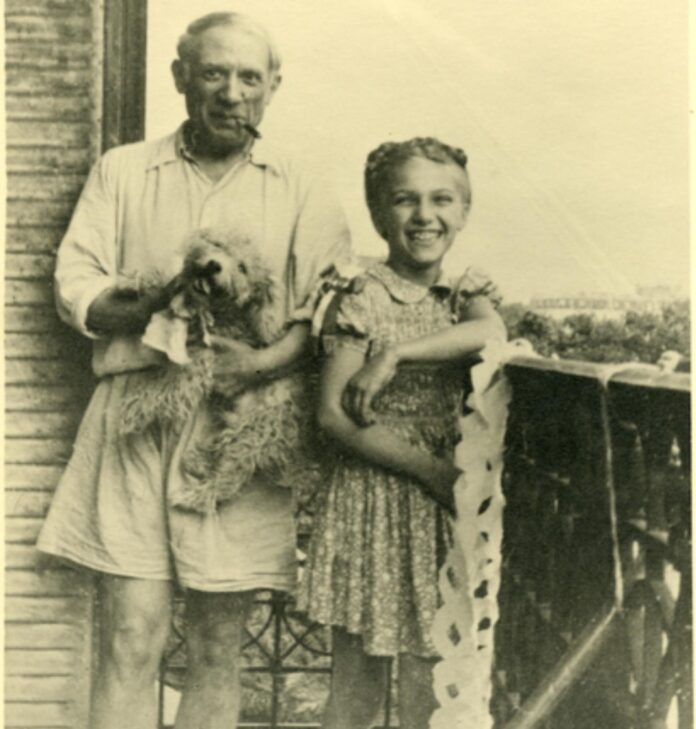

Maya Ruiz-Picasso. Paris, 1986

© Archives Maya Ruiz-Picasso

“For my mother it was a duty,” Diana says. “She was deeply attached to Picasso’s legacy. She became an expert of his oeuvre and gathered a great body of archives.”

The second exhibition in the museum shows the private life that Maya shared with her father, around the portraits he made of her in the 1930s. One of them had been stolen in a burglary in 2007 in Diana’s apartment and recovered by the French art police in a spectacular gang arrest. The exhibition also shows the numerous drawings, photographs, poems and other testimonies of their daily life. “He even kept bits of nails and hair, as a talisman to protect her,” Diana says. Another show currently at the Musée Montmartre in Paris is, in a first, dedicated to Picasso’s first wife, Fernande Olivier.

These exhibitions contribute to a growing movement to illuminate the role of the women in Picasso’s life. The painter has been described as a predator by the media and certain authors, especially in the wake of the #metoo movement. But alongside this, a more nuanced view is emerging, revealing an affectionate father behind the gruff exterior who was very attached to his children. Maya’s mother, Marie-Thérèse Walter, described him as “merveilleusement terrible” (wonderfully awful).

“He was Picasso! Of course his behaviour towards women can be questioned,” says Olivier of his grandfather, “but it has to be documented and placed in context. He was certainly not the monster that some describe.”

© Francoise Hugier

Maya herself was a character larger than life, capable of teasing French President Macron during an exhibition opening with the quip: “I could be your mother, you know”. She was born in Paris on 5 September 1935, eight years after Picasso’s met Marie-Thérèse Walter. He was 45 and she was 17. Her early life was not easy. As an illegitimate child, her birth and first years of childhood had to be “kept secret” she once said. She was named Maria de la Concepción, after Pablo’s sister who died when he was 14. But she could not pronounce the name and was nicknamed Maya. “It took me almost 60 years to have the name listed in public records,” she said.

“As an expert [on Picasso, my mother] authenticated thousands of works,” Olivier says. She stopped about 6 years ago when her eyesight began to fail because of a cataract. In 2012, Picasso’s son Claude and the other heirs formed a body named ‘Picasso Authentification’ which she did not take well, reminding them “I am not dead, you know!”

They dissented on the importance of provenance, after she authenticated drawings which had been stolen from Picasso and his family by handymen, considering authenticity to be the only matter of importance. “She was free, and I think all the expertise she developed was a way for her to continue living with her dad, with her own personality,” Diana says. Her death will now see the rise of a new generation of one of the most powerful families in the art world.