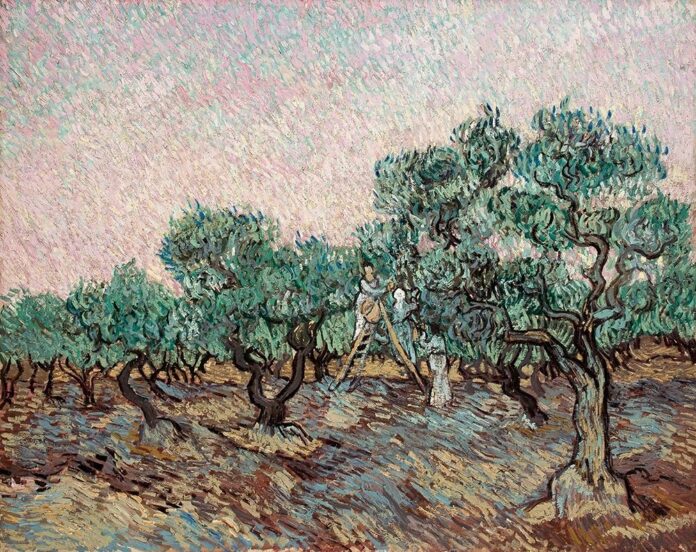

A new legal battle is brewing the realm of Nazi-looted art as the heirs of a Jewish collector sue New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation in Athens for the return of Vincent van Gogh’s 1889 painting .

The lawsuit, filed in the Northern District of California district court, contends that the Met secretly sold the painting in 1972 to avoid having to return the work to Hedwig Stern, who had sought its restitution. It is now on view at the Athens museum run by the family foundation of the late Greek shipping magnate Basil Goulandris and his wife, Elise Goulandris. The lawsuit was first reported in Courthouse News.

Stern, who was Jewish, fled Munich in 1936, moving with her husband and children to Berkeley, California, to escape persecution. The Nazi regime prevented her from bringing her art collection with her, and, in 1938, appointed Stern’s former lawyer, Kurt Mosbacher, to sell off her property, including five paintings.

The Basil and Elise Goulandris Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens. Photo courtesy the Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation.

Thannhauser Gallery—a business that was “Aryanized” when Paul Roemer took it over from the former Jewish owner, Justin Thannhauser—sold Stern’s Van Gogh, along with her Pierre-Auguste Renoir, to Theodor Werner for 55,000 Reichsmarks. Stern never saw the money from the transaction.

First, it went into a blocked account, which was one way the Nazis denied Jews access to their assets. Then, the Gestapo confiscated Stern’s property, including the contents of her bank accounts, in 1939.

Werner also wound up with a Gustave Courbet painting that had been Stern’s, which he gave back in 1955 when he realized the sale had been made under duress. But it was too late to restitute the Van Gogh or the Renoir, as he had already enlisted Thannhauser to sell the Van Gogh to collector Vincent Astor in New York in 1948. The Met subsequently purchased it from Knoedler Gallery in 1956.

The Stern heirs’ lawyers argue that the painting’s presence in Germany during World War II should have been a red flag unto itself, and that it should have been easy for the Met to track down its provenance.

A report filed along with the complaint—written by Jonathan Petropoulos, an expert on Nazi-looted art and professor of European history at Claremont McKenna College—makes the case that the museum quietly sold the work in the ’70s because it realized the illicit circumstances of the painting’s original sale.

Stern, who died in 1983, spent years trying to recover her looted art, including meeting in 1951 with Lane Faison of the U.S. Army Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Division in Munich. During the war, the Monuments Men worked to protect and recover objects of cultural heritage—and to return them to the rightful owners afterward. The complaint notes that Theodore Rousseau, then the Met’s chief curator, also served as one of the Monuments Men, and was a friend of Faison’s.

The broke the news of the secret sale in 1972, calling it an “unusual move,” and reporting the buyer as Gianni Agnielli, an “Italian industrialist” and associate of Marlborough Gallery. The Met claimed it had sold lesser works to fill more important gaps in its collections.

“We exchanged weak modern masters for strong old masters,” then-director Thomas Hoving told the .

Vincent van Gogh, (1889). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In a statement today, the Met reiterated that there was nothing unusual about the sale. The Van Gogh was “deaccessioned in a widely reported sale in 1972 that was part of a larger-scale and much debated effort to raise acquisition funds,” read the statement. “The sale of the Olive Picking met the museum’s strict criteria for deaccessioning—specifically, it was recorded that the work was deemed to be of lesser quality than other works of the same type in the collection. While The Met respectfully stands by its position that this work entered the collection and was deaccessioned legally and well within all guidelines and policies, the Museum welcomes and will consider any new information that comes to light.”

When Rousseau died, mere months after the sale, his obituary reported that the Van Gogh and other works had been sold to private dealers “for what outraged art experts said was half their value.” There are conflicting reports about the painting’s actual price tag, but in 2018, the paper’s obituary for another former Met curator put it at just $250,000.

“The only reason that makes sense to me for Rousseau and the Met deciding to sell off the painting in 1972 is that he or others in the Met’s leadership knew it was Nazi-looted art,” Petropoulos wrote. “Marlborough Fine Art, with its international branches, was well-positioned to place the painting discreetly.”

Basil and Elise Goulandris. Photo courtesy of the Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation.

The Goulandris Foundation did not respond to a request for comment by press time. Its website does not mention Stern in its provenance for the canvas, listing only the prior owner, Alfred Wolff of Munich, and then Thannhauser, Astor, Knoedler, the Met, and finally Marlborough Gallery. It states that it has been held in a “private collection” since 1972.

Prior to the opening of the Goulandris Foundation’s Athens museum in 2019, where is a highlight of the galleries, it was difficult for the Stern heirs to track down the painting’s exact whereabouts.

The family’s complex financial dealings, details of which were revealed in the Panama Papers leak, include offshore accounts and the transferring of paintings to shell corporations.

The Stern heirs are seeking the return of , the proceeds from the Met’s 1972 sale of the work, as well as damages in the amount of the fair market value of the painting.