More than a decade after the late film critic Roger Ebert made the controversial claim that “video games can never be art”, there is ample evidence to the contrary. An exhibition featuring many examples of the rapprochement between gaming and art in the digital age, boasting works by 36 artists including Rebecca Allen, Cory Arcangel and Suzanne Treister, opens 4 June at the Julia Stoschek Collection (JSC) in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Worldbuilding: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age (until 10 December 2023) marks the 15th anniversary of the JSC’s first public exhibition and explores the many ways artists have interacted with video games over the years as well as the potential for future innovation. It includes video, virtual reality (VR), artificial intelligence (AI) and game-based works from the mid-1990s to the present day.

“In 2021, 2.8 billion people—almost a third of the world’s population—played a video game,” the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, who is also artistic director at London’s Serpentine Galleries, said in a statement. “Video games are to the 21st century what movies were to the 20th century and novels to the 19th century”.

The exhibition, which also includes works by Peggy Ahwesh, Cory Arcangel, Ed Atkins and the Institute of Queer Ecology, will be on display for 18 months at the 115-year-old former frame factory owned by German art collector Julia Stoschek. A Berlin space, opened in 2016, houses her private collection that spans five decades of conceptual video, film projection, as well as computer- and internet-based works. The exhibition will also open at the Centre Pompidou-Metz in June 2023.

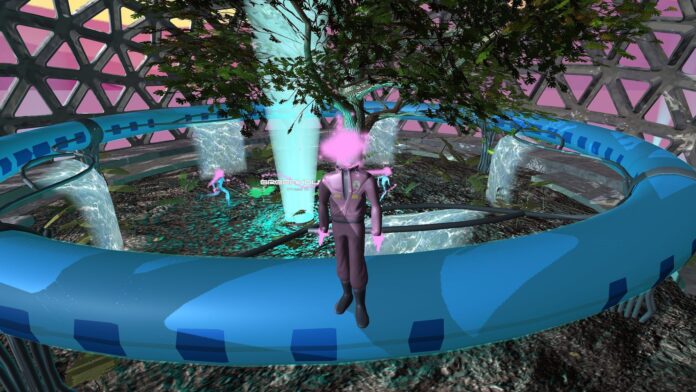

Rebecca Allen, The Bush Soul #3, 1999, interactive software installation, infinite duration, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist and ZELDA.

Nature is a dominant theme in the show, as seen in Rebecca Allen’s The Bush Soul #3 (1999). A pioneer in the field of computer art, Allen is credited with generating the first 3D model of the female body. Among her early endeavours was 1986’s Musique Non Stop, one of the first examples of 3D graphics applied to a music video, from Germany’s most revered electronic music export, Düsseldorf natives Kraftwerk. In the show, she immerses the viewer in pristine virtual landscapes inhabited by artificial life forms.

“The displayed works use technology to display pure landscapes that are reminiscent of the German romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich,” Stoschek said. “At a time where technology has taken us away from nature, some media artists, through simulation of nature, are working to compensate for this by working the other way round, attempting a reconciliation.”

In the installation PLAYER OF COSMIC ༄ؘ ° REALMS (2022), the all-female British collective Keiken (whose name means “experience” in Japanese) sees gaming as a spiritual act. “When we are going into these games, or alternate realities, we are transposing our consciousness into another realm,” says collective member Hana Omori. Visitors enter an all-white room where they are surrounded by white mounds of salt. A glowing haptic wearable womb is placed around the player’s mid-section that emits vibrations, animal noises and gurgles. The player lies down in a configuration that is reminiscent of a psychoanalyst’s couch, accessing private thoughts and feelings. According to Omori, the installation is an attempt to push physical boundaries in gaming. “One of the biggest questions when we’re creating immersive technology [is]: how does our physical body exist when we are playing a game?”

Keiken, Bet(a) Bodies, 2021–2022, wearable haptic womb, digital audio, 9 minutes 12 seconds, sound, silicone, LED light, minicomputer, haptics, amp. Part of Keiken, PLAYER OF COSMIC ༄ؘ ° REALMS, 2022, gamified installation, infinite duration, color, sound, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artists.

The exhibition seeks to showcase the work of artists from marginalised and underrepresented groups who have been overlooked in gaming for the last 20 years, “where a majority of video games are created by a very small, insular group of people coming from the realm of engineering and producing games from a very limited perspective”, said Obrist.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, Sudanese creator Lual Mayen has turned his personal experience as a refugee into a digital game titled Salaam (Arabic for “peace”). Developed over 7 years, players take on the role of a person fleeing a war zone, obtaining food, water and medical supplies. Mayen—who coined the phrase “gaming for good”—places gamers in a role where they become responsible for the actions of their avatars. The game has in-app purchases which can be bought with real money and are donated to NGOs involved in humanitarian work with refugees. The experience serves to remind players that being a refugee is not an identity but a circumstance.

Kim Heecheon, (썰매) Sleigh Ride Chill, 2016, HD video, 17 minutes 27 seconds, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist.

Ambitious in scope and vision, the exhibition leaves no doubt that video games can make for thought-provoking art. And while, at this time, the implications of inhabiting a metaverse are hard to predict, Worldbuilding shows that we have the potential to code a future grounded in beauty, creativity, empathy and spirituality.

- Worldbuilding: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age, 4 June 2022-10 December 2023, Julia Stoschek Collection, Düsseldorf, Germany