Feathers are sculptor Kate MccGwire’s primary medium, and they continue to fascinate her. “Human beings can’t make a feather that is so light, so thin; that has the color, the regimentation; that can allow something to fly, get wet…” she said. “We just can’t do it. We are incapable of manufacturing that, with all this technology that we have.”

With her writhing, undulating sculptures, it’s clear that MccGwire is a master of shape. But something else her works capture is time—there is a transportive sense of the primordial to them. They look untouched by the human hand. Are they coiled beasts from prehistory, or another dimension?

MccGwire’s breathtaking work combines science and craft—qualities that made her the perfect collaborator for “Forces of Nature,” which is the body of work for the inaugural installment of The Art of Wonder, a new platform from luxury whisky brand Royal Salute. One of the collection’s goals is to fuse the heritage of whisky making with art. MccGwire took on the task of exploring this ancient craft very meticulously, much as she approaches her own work. It all began with a trip to the oldest continuously operating distillery in the Scottish Highlands, Strathisla Distillery.

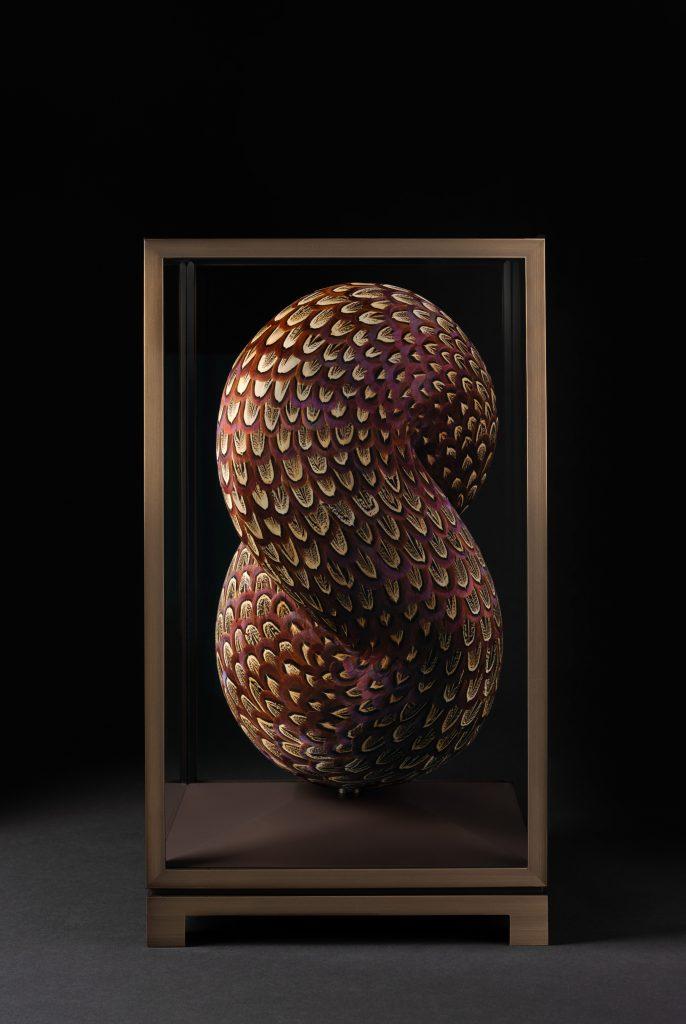

The limited-edition pairs a sculpture with a crystal decanter filled with 53-year-old blended Scotch whisky in a bespoke cabinet. Courtesy of Royal Salute.

“This project has been an incredible opportunity for me as an artist to experiment with new materials in an ambitious and unrestricted way,” MccGwire said. Her profound results are unveiled this week at Frieze London (October 12–16, 2022). The ambitious standalone sculpture, , incorporates oxidized copper from decommissioned whisky stills into MccGwire’s flowing language. Paragon is a series of 21 limited-edition sculptures available to purchase. Set inside a Scottish oak cabinet crafted by John Galvin Design, each sculpture is accompanied by a handblown crystal decanter hand-engraved with gold feathers and filled with a bespoke 53-year-old blend of Royal Salute Scotch whisky. The entire project is thoroughly documented with original photographs in a companion art book.

MccGwire took a break from her precise, painstaking work to speak with Artnet News.

The artist Kate MccGwire atop her floating studio on London’s River Thames. Courtesy of Royal Salute.

I’m fascinated by how you came to feathers as a primary medium.

I graduated from London’s Royal College of Art as a mature student in 2004—I had already been an interior architect before I went back to art school. I began my practice using animal byproducts: chicken wishbones. So, in a way, moving on to another element of animal detritus, feathers, was not unusual.

I left college and found a studio that happened to be on a barge; I had been brought up on the river, so being on a boat was not peculiar. Walking down to the studio every day, I’d pass this huge, disused and dilapidated warehouse on a rather run-down island, Platt’s Eyot, where they used to build high-speed craft and torpedo boats during the war. A workforce of women did the lion’s share of work on these incredible vessels. Today, the remaining boat sheds are cavernous, rusted corrugated iron structures but they have plenty of natural light and are a beautifully atmospheric place to photograph my work.

I’m rather besotted by the history of Platt’s Eyot. It’s got a whole series of workshops—people that run their own little businesses, me being one of them. There are musicians, woodworkers, and a prosthetic hand maker. Anything that you need to get made, you can get made there. It’s an ingenious little community, incredibly full of talent.

MccGwire’s pigeon-feather sculpture Vex (2008). Courtesy of the artist.

Pigeons roost in the warehouses here. Every day when I walked past, there was this sort of humming, cooing sound resonating around these buildings. I found feathers that had dropped from the birds, and I started picking them up. Within a couple of weeks, I had hundreds. They weren’t dirty, city pigeons. They were relatively clean, beautiful birds, and the feathers were exquisite; the gradations of color in each feather were remarkable. I started collecting and making work with them. I’m using materials that you can’t buy, which I feel adds to the disconcerting nature of the work.

I love the fact that a child will pick up a feather and put it in their hair, and suddenly they transform into a fairy or a tribal leader. Feathers are transformative objects in their own right.

A detail of MccGwire’s 2004 wishbone sculpture, . Courtesy of the artist.

You seem to really enjoy the craft part of getting down and dirty with your art.

A chicken wishbone piece that I made in 2004, , was made out of 23,000 wishbones and covered a wall that was 7.5 by 5.5 meters. Everyone recognizes a wishbone: many countries regard its shape as a symbol of luck. But the origin of the ritual of pulling the wishbone emerged in pagan times as the person who broke off the largest part of the wishbone would be the next one to get married, as the wishbone resembled the shape of the female pudenda. In later years the belief has evolved to be a symbol of luck.

I boiled all the wishbones myself and dried them on my kitchen table. Now I get help with many of the time-consuming tasks. I’ve got a wonderful team of assistants who sort, trim, and prepare the feathers in a way that I can then select them from organized groupings, almost like I’m painting. They’re producing my color palettes and I can work swiftly because I’m not hunting through piles of feathers.

In MccGwire’s installation , feathers spew forth in a kitchen. Courtesy of the artist.

Your entire team is female, which connects to this workforce of women who used to be at the neighboring factory where you find the feathers. The sorting process sounds exhaustive.

It is. My assistants are not necessarily people who have been to art school. They like the creative process and have an eye. And they like doing repetitive tasks. If you’re somebody that gets bored easily, it’s not the job for you. Some people really thrive at it; it’s almost like meditation.

Kate MccGwire and one of her pheasant-feathered sculpture editions. Courtesy of Royal Salute.

I’ve seen many of your sculptures, including the wishbone piece as well as the Royal Salute pieces. None of these really exude “bird” to me—but maybe dinosaur? There’s an aspect of connecting to something more primordial and universal.

Yes, I want the viewer to think of mythological creatures but also the creases and curves of the body, but not definitively human, bird, or reptile. It’s more of a living entity that is a hybrid thing between all creatures—birds, snakes, and humans. My work is always muscular, energetic and tense as if they could suddenly become alive. But they are confusing; they resemble something real by the way the feathers are layered but they don’t make sense, there is no head or tail.

It does make sense, actually. So, all of this informs the Royal Salute project. Let’s first talk about , which is a limited edition of 21 works. How did you formulate it? The shape makes me think of infinity—it just seems to coil and coil.

Exactly. Well, it had to be something that was neat and perfect and worked on a scale with the Royal Salute decanter but still maintained the tension and complexity that is intrinsic to what I do. I have never made an edition before, so that was quite a challenge. I needed something that was flowing and undulating but was resolved as a shape, like a mobius strip.

MccGwire found inspiration in these otherworldly, disused whisky stills. Courtesy of Royal Salute.

It’s striking to see metal merged with feathers in .

We went to Strathisla Distillery, the oldest continuously working distillery in the Scottish Highlands, and then on to visit the stills maker Forsyths. Every one of those stills is beaten by hand. They are made from flat pieces of copper that are hammered into bulbous shapes. The craftsmanship was incredible.

It’s painstakingly detailed work, and these sort of onion-shaped curves have to fit together perfectly to function and it’s all done by hand. I hadn’t seen that level of craftsmanship anywhere before. They let me look around the redundant stills all assembled together like a graveyard. Each of the stills has a unique verdigris patina caused by the alchemical process of distilling. I just fell in love with these amazing shapes; it really sparked my imagination and I wanted to bring everything back to the studio.

The metal-and-feather hybrid creation Protean. Courtesy of Royal Salute.

Do you think that you will incorporate this metalwork in future projects?

I’d love to. The still elements make phenomenal shapes that I would be unlikely to achieve myself. Using them is an inspirational starting point for my work.

The softness of the feathers against the metal is interesting; they’re both super-strong materials.

Yes, absolutely. But in completely different ways. And so is the difference between the outside surface of this sort of burnished copper—the orange color that you see—and the inside surface that is tinted and discolored. You have that beautiful sort of aqua green on the inside, pitted into the surface where the process of the whisky distilling has marked it. The history of whisky is in that piece of metal.

I love that my work with Royal Salute has connected me with many incredibly skilled and talented craftspeople—like a guy who hammers metal to make a whisky still.

‘s crystal decanter component was handblown by Dartington Crystal, Devon, and engraved with a design of feathers inspired by the sculpture in 24-karat gold. Courtesy of Royal Salute.