It would seem that it is difficult to lose the castle. Anadolu Agency reported that during an expedition, a group of archaeologists discovered one in eastern Turkey.

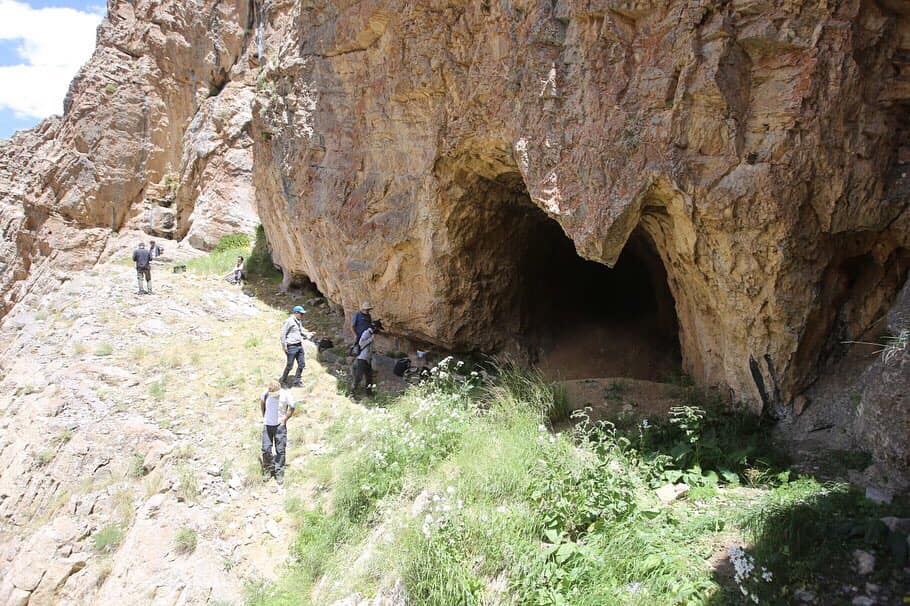

The castle is located in the mountains of the Gürpinar region in the eastern province of Van, 8,200 feet above sea level. There, the team found ancient walls, a water storage tank, and several pieces of pottery. Although the structure has not survived, the piles of stones give the outline of the former foundations and walls.

Although the structure has not survived, the piles of stones give the outline of the former foundations and walls. The 2,800-year-old castle was repopulated during the medieval period, according to Rafet Cavusoglu, leader of the excavation team and professor of archeology at Wan Yuzunju Yil University, who sponsored the excavation project.

In the state of Urartu, the stone was widely used in construction. This is indicated, in particular, by megalithic monuments and numerous dolmens. Numerous ruins of ancient fortresses made of large stones were also found in different parts of the state. According to Cavusoglu, during the expedition, scientists discovered that limestone and sandstone were used in the construction of the walls in the region. He notes that the castle was a very important discovery for archeologists.

It is believed that the castle dates back to the Kingdom of Urartu (also known as the Kingdom of Van). The Kingdom of Urartu once occupied the territory of what is now Eastern Anatolia.

The reign of Urartu was short-lived, from about 860 BC. E. – 590 BC E. The end of the kingdom was mysterious. Most of the sources on Urartu were written by the Assyrians or other enemies of Urartu. Their brief success came during the temporary decline of the Assyrian Empire in the 8th century BC. E.

The king of Urartu Ishpuini captured the ancient city of Musasir, which became the holy capital of the Kingdom. However, not much is known about the city’s history, especially after a shipment of artifacts from Musashir was lost in the 1850s.

The British Assyrian Excavation Fund removed numerous objects from Musasir and sent them up the Tigris River. On the way, the convoy was intercepted by local Arab raiders. During the fracas, the ancient treasures of Urartu fell into the river, where they have remained since then.

Another discovery of Urartu artifacts occurred in 2014. Live Science reported the discovery, made by residents of a Kurdistani village in northern Iraq, of the bases of columns depicting the Urartian supreme god Khaldi. They are believed to belong to a temple at Musasir (although dating suggests this may have been done after the fall of Urartu when the Assyrians returned to power).

The excavation of the castle is ultimately a rare opportunity to learn more about the opaque history of Urartu. It is noteworthy that the kingdom was a major producer of art, especially metalwork, and was known for controlling territories with military force, using built fortresses.

While more research is needed to determine the castle’s functionality, the mayor of nearby Gurpinar, Khairullah Tanis, told Anadolu that the find added cultural wealth to the province and “thrilled us in terms of tourism and culture.”

Urartu Castle built by Iron Age peoples

The Iron Age people known as Urartu built buildings that are now flooded under the lake. At some point, residents were forced to leave the area after the water level rose due to a volcanic phenomenon.

The area, located southeast of the Black Sea and southwest of the Caspian Sea, was part of an ancient civilization that first emerged on the shores of Lake Van in the early 13th century BC.

The people of Urartu had significant political power in the Middle East during the ninth and eighth centuries BC. But they ultimately lost control of the region after conflicts with the great Assyrian empire.

Archaeologists say that in the seventh century BC, the entire civilization, with its high castles built on top of mountains, stone irrigation canals, and steles reflecting the great events of its history, seemed to disappear into thin air.

They claim that this was due to the invasion of the Scythians, Cimmerians, or Medes. According to historian Mark Cartwright, Urartu was considered a special, much more ancient culture only after excavations carried out in the 19th century.

During their reign, the Urarts were known for their impressive architectural designs, including an irrigation canal nearly 50 miles long and ornate temples. These religious structures were often decorated with engravings that paid homage to local customs, with the lion being a popular Urartian motif, for example, as noted by Owen Jarus for Live Science in 2017.

Last year, AA reported on a group of Turkish restorers who restored stone carvings at the 2,700-year-old Alanis Castle, which sits atop a hill overlooking Lake Van. One of the best-preserved heritage sites associated with a mysterious civilization, the Khaldi Temple in the castle, whose walls were adorned with “one-of-a-kind” intaglio ornaments, excavation leader Mehmet Ishikli, an archaeologist at Ataturk University, told AA.

Other recent finds related to Urartu range from the grave of a noblewoman buried with her jewels in Cavushtepe Castle, also in Gyurpinar, to a 2,800-year-old open-air temple at Harput Castle in the eastern Turkish province of Elazig.

In April, the Hurriyet Daily News reported that the temple, consisting of an oval and flat square used to house sacrificial animals, as well as various niches, seats, and steps, was likely used for major religious ceremonies honoring Khaldi, the Urartian god of war.

Since this region is often subject to strong earthquakes, few traces of Urartian buildings have survived in the Encyclopedia of World History. Interestingly, Cavusoglu previously led excavations at Cavushtepe Castle, which suggested that the Urarts used a construction technique called “locked stones” to protect their fortifications from aftershocks, the Daily Sabah reported in 2019.

Archeologists hope that the new find will shed light on the culture and architecture of Urartu.