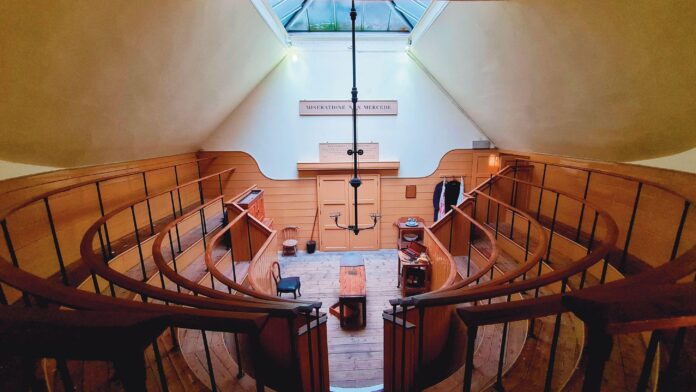

Noon on Fridays was a time of terror and hope in a church attic in London, a strange and eerie space, which, two centuries ago, was an operating theatre where the line between life and death was marked by the skill and speed of the surgeons, lit only by sunlight pouring through a skylight — one that will be recreated again this winter.

The Old Operating Theatre and Herb Garret, hidden away in the roof of St Thomas’s church in Southwark is celebrating its 60th anniversary as a museum and the 200th anniversary of its construction. It is the oldest surviving operating theatre in Europe and the second oldest in the world.

When train tracks carved up Southwark in the late 19th century, the hospital moved to its present site in Lambeth and the church became storage for neighbouring Guy’s Hospital, its attics forgotten and abandoned. Then, in 1956, Raymond Russell, a maverick musician and scholar interested in medical history, read a curious piece about medical students attending operations in a church attic. He realised this could be St Thomas’s, got permission to climb the bell-tower ladders and crawled into the attics through a hole in the brickwork. Russell died in 1964, aged just 42, but he saw the museum open through a trust led by Lord Russell Brock—a pioneering heart surgeon at Guy’s, one of many eminent medical supporters fascinated by its history.

The restoration included the adjoining garret used by the hospital’s apothecaries to dry and prepare medicinal herbs, and relied on surviving original fragments and paint traces, marks and scars showing where structures had been. But Sarah Corn, the museum’s director, says the skylight itself was the best that could be done with available resources, closer to a 1950s conservatory and now failing. The original was crucial to the operating theatre, which served the women’s ward. Previously operations, including amputation of limbs, trepanning and mastectomies—without any form of anaesthetic until the late 1840s—were carried out in a curtained-off corner of the ward until it was realised there was space in the church attics just the other side of a party wall; the connecting door, now leading only to a blank wall, is a recent restoration.

Patients were poor but not destitute. They had to pay for their bedding and medicines—for they had been carefully selected as “working and deserving”. The surgeons gave their time free on Fridays, teaching students packed in on five steps around the horseshoe operating space. Operations were performed from noon when the daylight was strongest; gaslight only came a few years before the space was abandoned. Survival depended on escaping fatal blood loss, shock or infection in a space where everything, including the surgeon’s hands, was only cleaned at the end of the day’s work. But the survival rate was actually an impressive 70%. Patients knew that certain death was the only possible alternative.

The museum will close in late December for three months of restoration works, which are being carried out with a £157,230 government grant via the Museum Estate and Development Fund delivered by Arts Council England. The new timber and glass skylight will be closely modelled on Georgian examples, and Corn hopes it will light her extraordinary space for at least another century to come.