The books team at The Art Newspaper has waded through the piles of art tomes published this year so you don’t have too. Below, each editor has picked three publications that shone through in 2022.

Jacqueline Riding, contributing editor, books

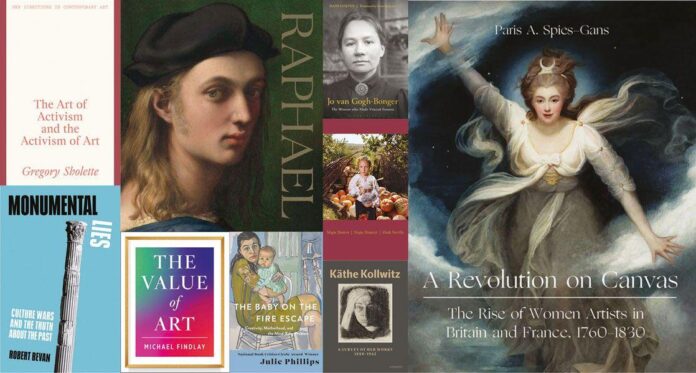

A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France 1760-1830 by Paris A. Spies-Gans (Paul Mellon Centre/Yale)

The miniaturist Sarah Biffen (subject of the excellent Without Hands show at Philip Mould gallery in London, until 12 December, and accompanying publication), born with no arms or legs, was one of many professional women artists to exhibit in major venues in Paris and London between 1760 and 1830, beyond the few currently celebrated (Angelica Kauffman, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, etc.), as Spies-Gans’s exhaustive, groundbreaking research reveals in this beautifully produced book.

Käthe Kollwitz: A Survey of Her Works 1888-1942, edited by Hannelore Fischer (Hirmer/Käthe Kollwitz Museum)

This year has been a particularly good one for stand-alone publishing on historic and Modern women artists, and women’s significant influence within the international art world—fingers crossed this signals a shift (at last) from niche to mainstream. Honourable mention goes to Lund Humphries’s Illuminating Women Artists series, with two books in the bag (Luisa Roldán and Artemisia Gentileschi) and two more scheduled for 2023 (Elisabetta Sirani and Rosalba Carriera). It was a brutal selection process, but the first of my top three, from the many excellent books we reviewed over the last year, is Fischer’s Käthe Kollwitz. Kollwitz’s brilliance requires no introduction, but this exquisitely illustrated survey, while exploring her many iconic works, draws attention to lesser-known imagery including her subtly erotic subjects.

Jo van Gogh-Bonger: The Woman Who Made Vincent Famous by Hans Luijten, translated by Lynne Richards (Bloomsbury)

Chicago University Press’s first English translation of the Parisian art dealer Berthe Weill’s 1933 memoir was pipped to the post by this superb biography of the equally extraordinary Jo van Gogh-Bonger. So much has been written on Vincent van Gogh that you wonder what more can be said. It turns out much more on the woman who was the early driving force behind the Dutch artist’s legacy.

Gareth Harris, book club co-editor and chief contributing editor

Monumental Lies: Culture Wars and the Truth About the Past by Robert Bevan (Verso)

More and more commentators are making their voices heard in the clamour around today’s so-called “culture wars”, outlining the ideologies behind the destruction of, for instance, historic statues. Bevan astutely argues that those who manipulate our cultural past are shaping our future, making the case that historic buildings have become battlegrounds for right-wing and nationalist political arguments. Interestingly, he also questions the authority of Unesco. In one of many polemics, he says: “At the same time as its role in protecting culture has become suffocated by national interests, Unesco now appears to operate on the premise that any wartime damage should be undone.”

The Value of Art by Michael Findlay (Prestel)

This updated version of The Value of Art, first published in 2012, features important new material, focusing on, for instance, the rise of NFTs. Findlay asks, “where are the NFT art critics?… there is little discourse on the relative aesthetic qualities of the images themselves”. He also has strong opinions on “protest art”, saying: “In very broad terms, artists represent the protesting class while collectors represent the museum trustee class, and while the cultural ecosystem needs both, on issues of social justice they are often on different sides of the barricades.”

The Art of Activism and the Activism of Art by Gregory Sholette (Lund Humphries)

As a key member of the activist group Gulf Labor Coalition, Gregory Sholette has a unique perspective. Sholette examines this fascinating subject “from the perspective of an artist and activist who has been active in the field since the 1980s,” writes the art historian Marcus Verhagen in the introduction. This informed analysis spans more than 60 years of art activism, from the Situationist International group of social revolutionaries (1957-72), which directly engaged with the student uprisings in Paris in May 1968, to Black Lives Matter today, which has “unquestionably set a new high bar for protest aesthetics”, Sholette says.

José da Silva, book club co-editor and exhibitions editor

Stop Tanks With Books by Mark Neville (Nazraeli Press)

Neville’s photobook of Ukrainian life before Russia’s invasion in February is both a call to arms—the photographer sent 750 free copies to influential people who might “have it in their power to help Ukraine”—and a stark reminder that Ukraine was already at war in its east, as depicted in the photographs of soldiers manning trenches and checkpoints. However, it is the tender portraits of everyday life—people at the beach, in school, at a rave, eating ice cream—that really bring home the tragedy that has unfolded in Ukraine.

The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood and the Mind-Baby Problem by Julie Phillips (W. W. Norton & Company)

While most of the case studies in this book are from the literary world, the opening section on Alice Neel is a searing account of the complexities of balancing (or not) being a mother and an artist—and the often heavy price women pay. Neel, for example, can sometimes come across as brutal and uncaring, but these labels would rarely be used to describe an artist father in the same situation. Neel said that for much of her life she felt she “didn’t have the right to paint because I had two sons”. The book explores the difficult issues around the subject with no judgment and or neat conclusions—and is all the richer for it.

Raphael by David Ekserdjian, Tom Henry et al. (National Gallery Company Ltd)

If you missed the standout Raphael show at London’s National Gallery earlier this year, its catalogue is the next best thing. The rich imagery and texts make it the perfect coffee table book for art history buffs to dip into over the holiday season. There are also tasty titbits to tell the family over Christmas lunch, such as the belief that the Vatican’s foundations began cracking at news of Raphael’s death. Or when Munich’s Alte Pinakothek sold Raphael’s masterpiece Bindo Altoviti because it was believed at the time to have been painted by his assistant Giulio Romano, to buy what turned out to be a discredited Matthias Grünewald…