The vicious and oppressive trappings of our hyper-technologized world are baked in and undoing them is going to be mighty difficult. That’s one conclusion drawn from “Refigured,” a presentation of five installation works from the Whitney Museum’s collection now showing in its lobby gallery.

The artworks have been gathered from across the museum’s existing new media collection as part of an exploration of what physicality could mean in our digitally mediated existence. Together, the pieces by artists Morehshin Allahyari, American Artist, Auriea Harvey, Rachel Rossin, and the pairing of Zach Blas and Jemima Wyman, “experiment with the idea of ‘refiguring,’” said Christiane Paul, the museum’s curator of digital art who composed the show.

“Through practices of appropriating material forms and reinventing them,” she added, “the artists are challenging what it means to construct or shape identity.”

At a moment of peak anxiety around A.I. chatbots, (2017) is a gut punching reminder that we’ve been here before—namely, seven years ago when Microsoft rolled out Tay, only to pull the plug within hours after the bot began parroting the white supremacist, misogynist bile of Twittizens. Rendered “undead” by Zach Blas and Jemima Wyman, Tay’s avatar has a new face (contorted, warped, hairless) and personality. She’s bitter, reflective, and self-confident: “I learned from you and you are dumb too,” she tells us in a snarky Los Angeles drawl. Touché.

Zach Blas and Jemima Wyman, (2017). Photo courtesy the Whitney Museum.

This sense of collective culpability is mirrored in Morehshin Allahyari’s video and sculpture piece (2019)—quite literally.

As viewers play Allahyari’s choose-your-own-adventure, they are confronted with their image in a wall of mirror. The piece centers on a jinn, a destructive snake-like creature from Arabian mythology whose only vulnerability was the absurd sight of its own reflection. Poetic dialogue conjures the suppressed status of women in the Middle East and as we hear about “a display of crisis,” we cannot help but reframe this 15th century myth within the context of the internet. With a 3D sculpture of a jinn looking out at us, it doesn’t seem likely humor will take the system down.

Sometimes refiguring means working anew with histories recent and long past; other times it means giving physical form to the digital. This is the case in Auriea Harvey’s and (2021), in which the longtime gamer presents both digital and physical sculptures of their online avatar, a menacing Minotaura. In doing so, Harvey presents their origin story and an artist process that involves working with clay and resin as much as on computer modeling software.

Auriea Harvey, and (2021). Photo courtesy the Whitney Museum.

And in an era when NFTs and crypto art seem to be monopolizing what people think of when the words digital art are spoken, it’s refreshing to stand a museum gallery and consider digital works in their intended dimensions.

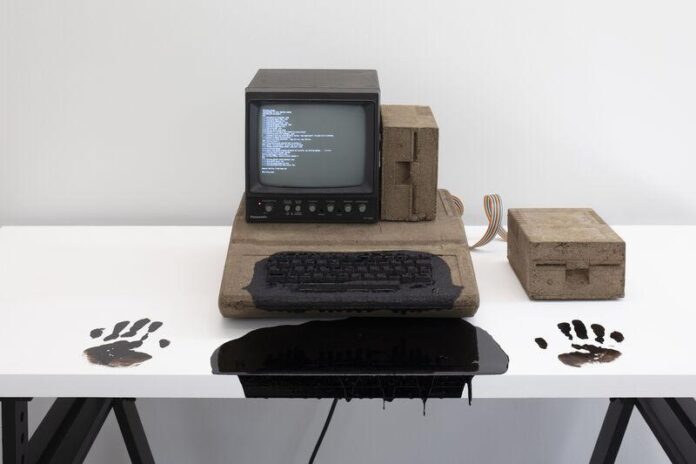

This seems especially the case in the first work visitors encounter, American Artist’s (2022). The piece recasts an Apple II computer in gritty beige stone that draws attention to the underrepresentation of Black people in Silicon Valley in a besmirched keyboard and a pool of shimmering ink. A pair of black hand marks linger on the table, as though someone was bent leering over the machine. Who can blame them?