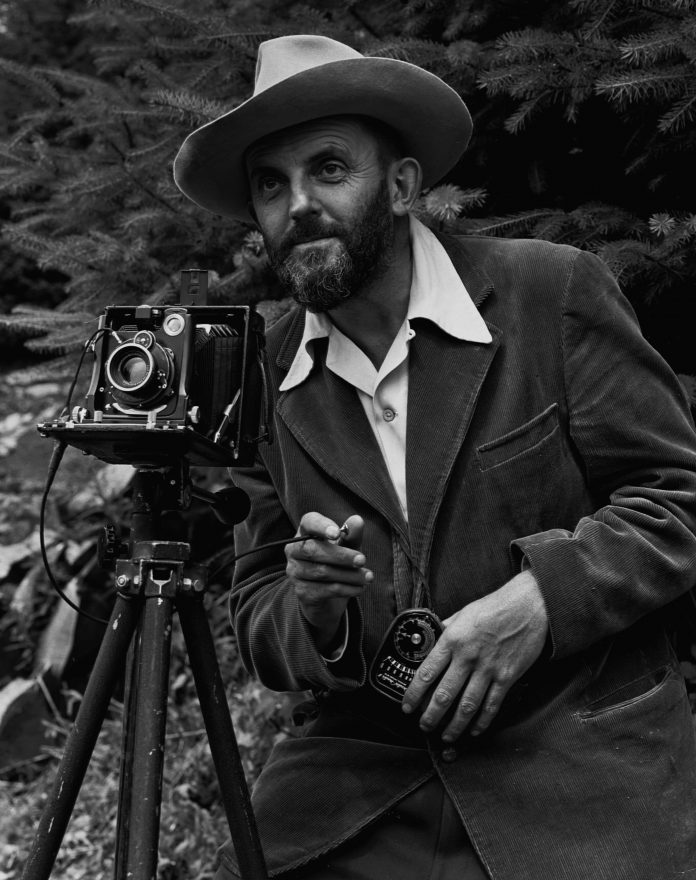

A photo is not taken, it is created,” says Ansel Adams. This brief statement sums up more than fifty years of the relentless pursuit of perfection: Adams spent his entire life experimenting to enhance the expressiveness of photography; he studied the techniques, photographic processes, chemistry, and physics of photography to the finest detail; he developed a ‘zone system’ of photography through which tens of thousands of people learned to look at the way the camera looks and to mentally see the end result before choosing the aperture and lens; and finally, Adams always treats photography as a form of visual art.

According to Adams, he aims to capture a ‘simple lens reading’. But he’s the first to claim that the lens plays a service role and is only capable of what the photographer will make him do. The receptivity of a lens does not exceed that of a photographer. Shooting doesn’t mean pressing a button, and clicking the shutter doesn’t look like an automatic beacon flashing. Photography is a special way of seeing, the ability to imagine the world in a range of gray tones and conveys it with impeccable clarity.

By 1932, Adams had already arranged a solo exhibition and, together with Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, and other photographers, founded the F/64 association; the first group exhibition of these photographers at the Musée de Young in San Francisco was a milestone on the road to making photography an independent and full-fledged art form and using the camera not as a brush stroller but as a way of artistic vision. Although the F/64 association self-destructed about a year later (Adams and Weston both insisted on it, fearing the emergence of the circle), neither Adams nor Weston nor any member ever gave up on the desire for image accuracy and sharp focus – the basic principles of F/64, which remain valid today.

Adams was helped by his musical education: music played the role of a guide on the way to becoming a photo artist. It helped him to compare the negative with the notes, and the positive with the performance and translate into photography the desire for maximum clarity of tone. Music also taught him that technique is the mainstay of his skill. A future pianist should exercise for seven to eight hours a day, achieving complete obedience to the keyboard. A future photographer should also exercise until he feels that the camera has become a natural extension of his hand and eye and should master the technique perfectly. Music deals with sound and photography deal with light, but here and there you should strive for perfection, for the perfect harmony of sound or light combinations.

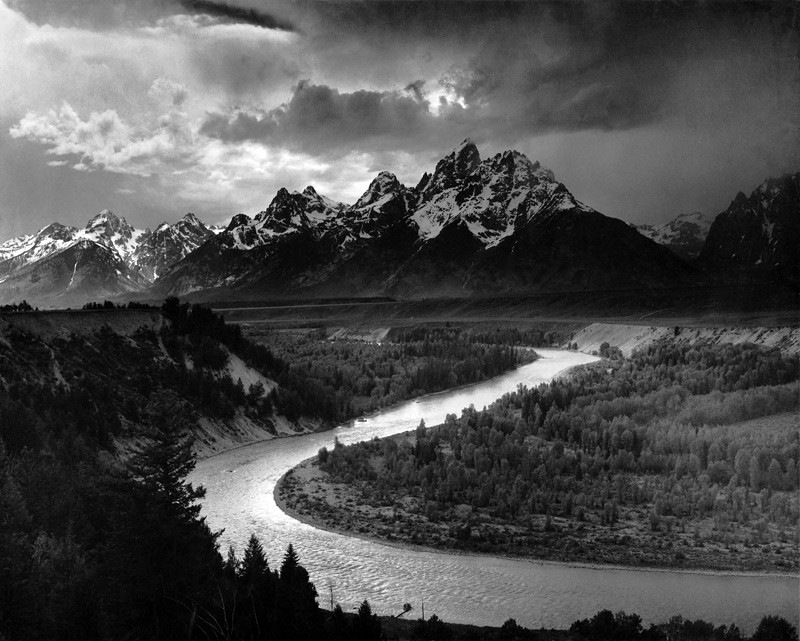

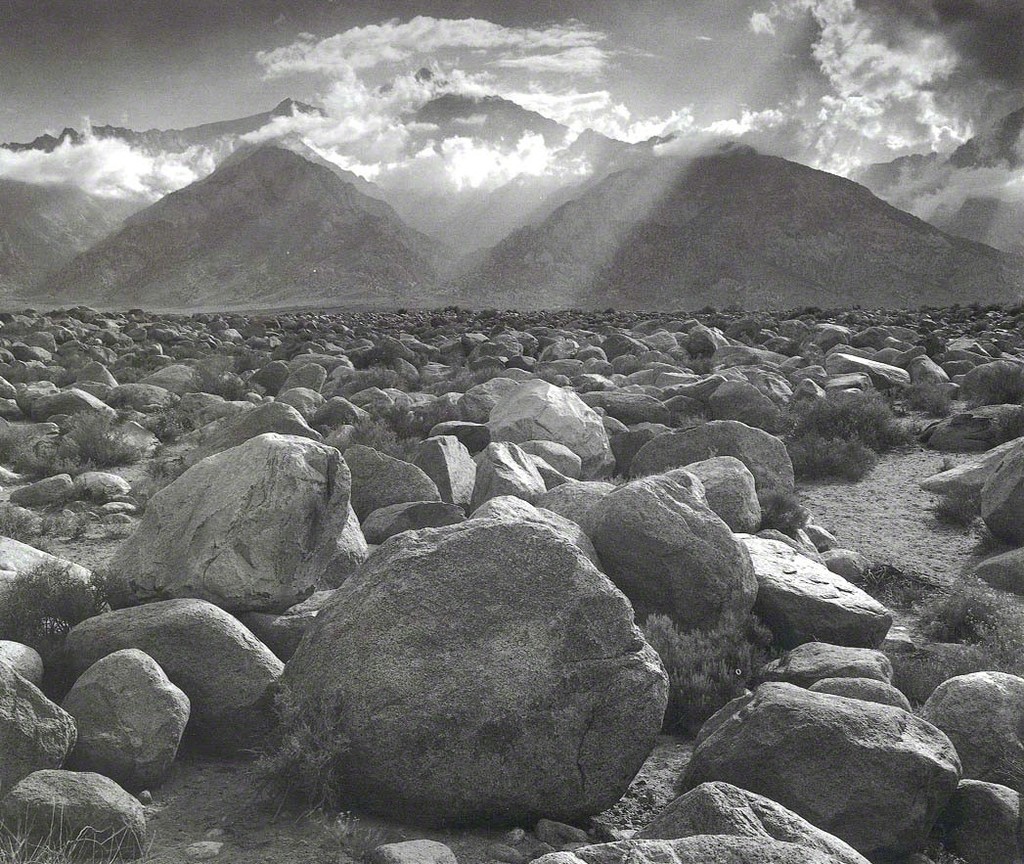

Perfection decided Adams, it is a faithful transmission of the artist’s vision: not just visual perception, but a full impression, in all its complexity, with the help of positive, enclosed in certain boundaries and speaking the language of light tones – from almost white to almost black. In nature, Adams points out, there are bright or subdued colors, but the photographer must learn to see them translated into a scale of gray tones; in addition, in nature, strictly speaking, there are no planes, only volumes. Imagination translates three-dimensionality into two dimensions, and the obedient technique faithfully reproduces these forms in the system of symbols of photographic art, and the visible image impresses the viewer more than the object itself in reality.

Zone system

Not many photographers take photography as seriously as young Adams did, and there are even fewer, if any, photographers who, on the one hand, would be gifted with a subtle artistic flair, on the other – would perfectly own the technique of photography. In just a few years Adams has become a recognized master of photographic technique, and from this position, he does not leave, continuing to experiment forever, seeking to expand the possibilities of photographic art, constantly deepening and improving his skills. Even now, having gone beyond seventy, he has not abandoned his experiments, although he has long-established the limits of all the existing types of lenses, filters, exposure meters, and films, all methods of photography, photographic paper, exhibitors, and processes. Its ‘Area System’ exposure, by placing the illuminated surfaces of an object on the negative exposure scale, provided everyone with access to the principles of sensitometry and greatly eliminated the need to guess or calculate some average exposure time. Its system has sufficient flexibility and ultimately puts the technique at the service of the photographer’s inner vision.

Adams shared his experience with everyone. His five books, united under the common title ‘Fundamentals of Photography’, and his own ‘Photographic Guide’, as well as the workshops and seminars he began in Yosemite Park in 1940 at the invitation of the magazine ‘J.S. Camera’, he resumed in 1945 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and since 1946 he has held annual meetings in Yosemite, all of which were made for both amateurs and professionals by teaching theory and practice of photography. In recent years, studio classes have been added to the list at the University of California at Santa Cruz. In photography, Adams was and remains a first-class artist and master, teacher and consultant, to the bone a professional.

Literature analogy

What is fair to one art form is fair to others as well. Joseph Conrad once also disdained simple verbal dexterity, noting that having a gun does not mean being a hunter or warrior. And when, in the famous preface to the novel ‘Negro with Narcissus’, he described what he as a writer aspires to, his words sound as if they mean photography and come from the mouth of Ansel Adams: ‘First of all, I want you to see. This – and nothing else, but it covers everything. Like Conrad, Adams understands the word ‘see’ to mean more than just ‘capture reality. Adams suggests that we don’t look, but that we look. The mystery of his images, as well as his shadow, is never completely black, impenetrable: under the ghostly cover of it there are meaningful outlines, in the shadows, there is a wealth of details hidden. Its clouds and snow are never whitewashed and the sky is rarely serene.

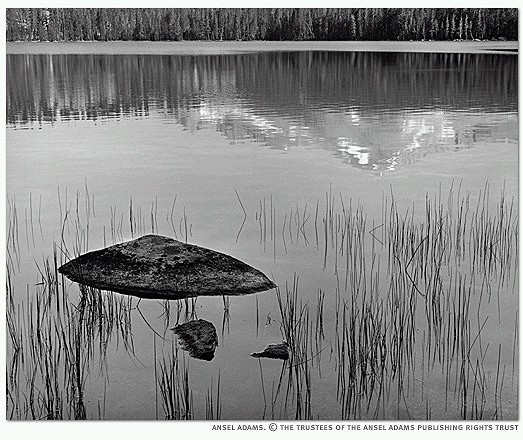

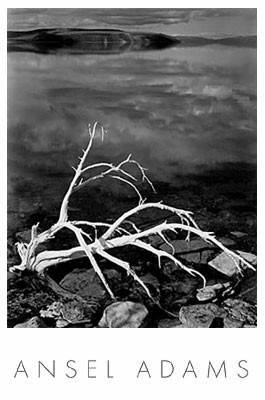

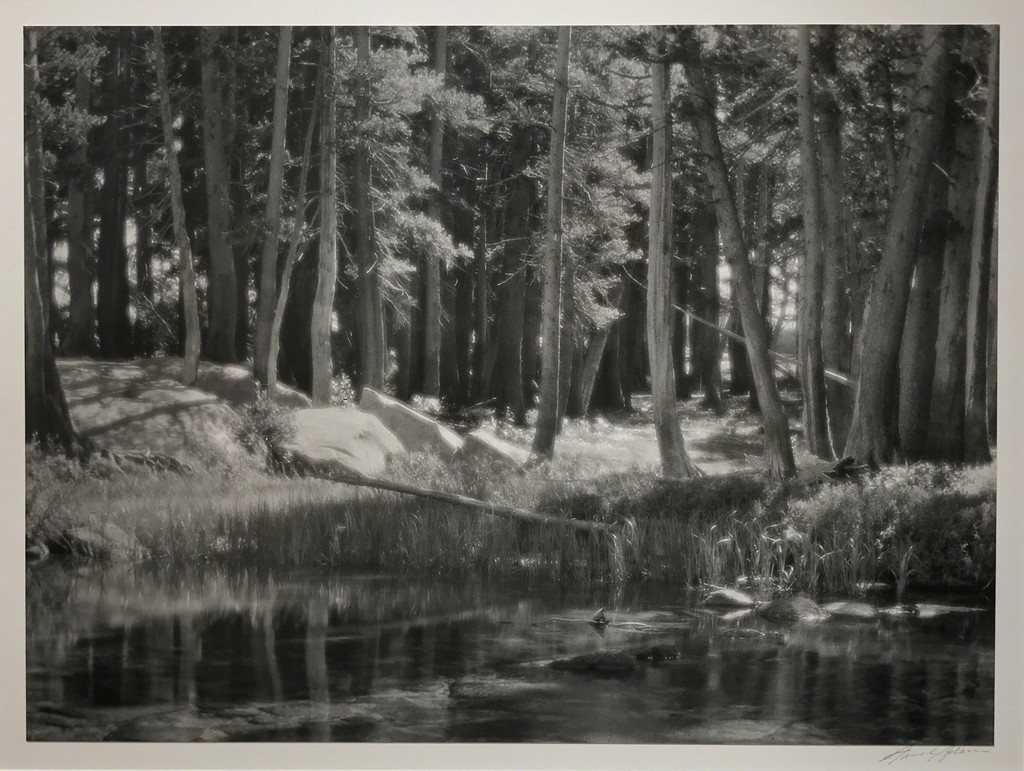

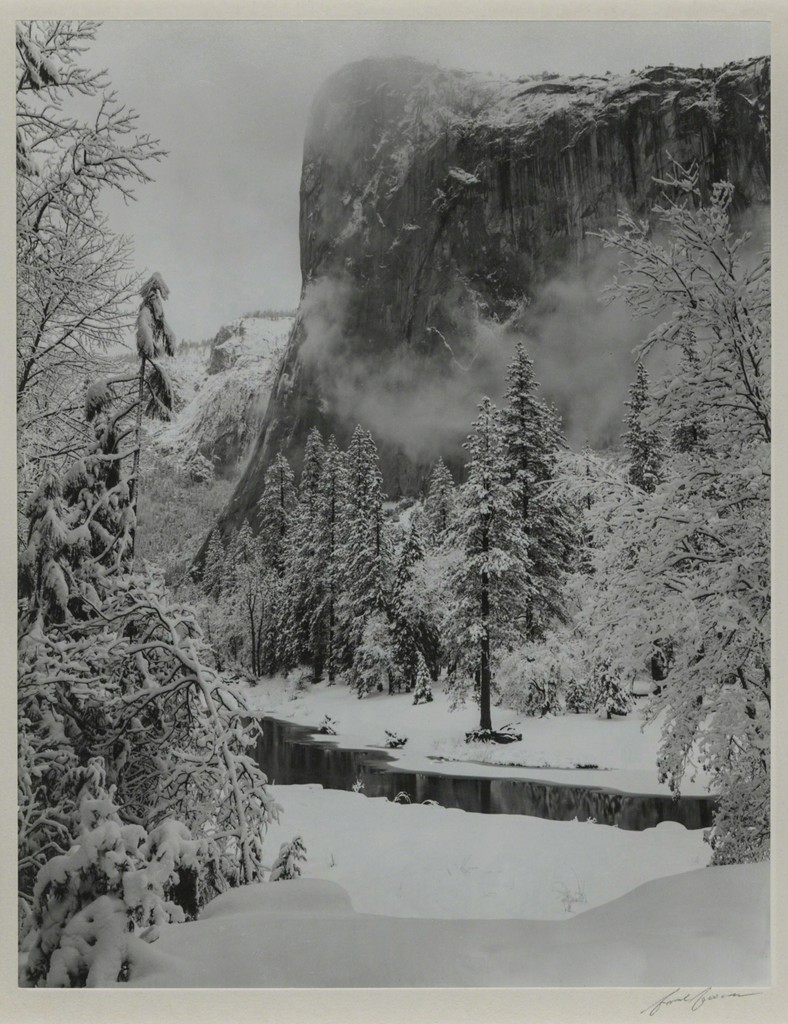

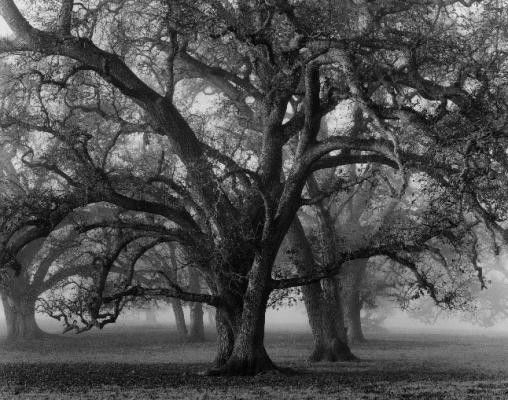

In a sense, Adams says, each object can be considered as a set of tones. But its tones, no matter what step on the scale of light they occupy, are complex, devoid of sharp, unsoftened contrasts, and are not just light values corresponding to the images of rocks, trees, and falling water. They fill the viewer with awe before the visible forms of the world. Without losing their clarity and clarity, they sound like hymns to the strength, tenderness, and beauty of the earth. Looking properly at the typical work of Adams, the viewer finally declares confidently: “I see it!” wanting to say that he does not just see it, but understands and feels it.

In a sense, Adams says, each object can be considered as a set of tones. But its tones, no matter what step on the scale of light they occupy, are complex, devoid of sharp, unsoftened contrasts, and are not just light values corresponding to the images of rocks, trees, and falling water. They fill the viewer with awe before the visible forms of the world. Without losing their clarity and clarity, they sound like hymns to the strength, tenderness, and beauty of the earth. Looking properly at the typical work of Adams, the viewer finally declares confidently: “I see it!” wanting to say that he does not just see it, but understands and feels it.

Adams does not think of using the camera to capture reality in the manner of so-called ‘photographic realism’. On the contrary, he believes that ‘the more photography approaches the direct reproduction of reality, the more it distances itself from its aesthetic perception’. Guided by this and other considerations, he favors black and white over color photography. In black and white, a transparent cold separates our world from its symbolic image. Black and white require the artist to reinvent himself, it does not allow for the cheap effects that Adams ridiculed in his advice to the supporters of color photography: ‘If it doesn’t work out better, make it red.

Adams does not think of using the camera to capture reality in the manner of so-called ‘photographic realism’. On the contrary, he believes that ‘the more photography approaches the direct reproduction of reality, the more it distances itself from its aesthetic perception’. Guided by this and other considerations, he favors black and white over color photography. In black and white, a transparent cold separates our world from its symbolic image. Black and white require the artist to reinvent himself, it does not allow for the cheap effects that Adams ridiculed in his advice to the supporters of color photography: ‘If it doesn’t work out better, make it red.

Adams is like the poet Walt Whitman in his quest to ‘see the unpretentious in a humble and mysterious light’. In the frosted glass, he does not see a reproduction of a painting of the world, but the painting itself, his impression of it, and therefore his works, like any real work of art, are, in a sense, a self-portrait. ‘The work of photographic artfully reflects the photographer’s feeling towards the object being photographed, and therefore fully reflects the photographer’s vitality. At the same time, Adams’ art is the art of ‘finding objects’, not just the ability to organize, process and compose them. By composition, Adams understands the ability to see in the best way possible. All preparation of an object for the shooting is limited to removing unnecessary objects from the field of view; Adams takes photos in natural light and rejects unnecessary tricks and tricks of laboratory processing, which are often used to turn bad pictures into good ones. The size of the treatment Adams uses is determined by the requirements of the negative or positive itself: the desire to bring it to the state intended by the photographer’s inner vision before taking the picture. As a magician and sorcerer of a darkroom, Adams does not use the magic available to him to cheat, but he does not want to fall victim to the inexperience or dishonesty of others. He prefers to sell his works as individual positives or entire albums. If they are reproduced by the printing process, he himself oversees the work of the printer, because a long time ago he studied printing so much that professionals have something to learn from him.

Stiglitz Influence

Any conversation about Adams’ views on life and art should inevitably concern Alfred Stiglitz, whom Adams met in 1933 and who in 1936 arranged a personal exhibition for the photographer – the first exhibition of a single photographer under the auspices of Stiglitz since his last debut in 1917. Adams Stiglitz’s admiration for him is quite natural: we are always fascinated by the qualities inherent in part / ourselves. The Stiglitz confirms Adams’ faithfulness to photography as an art and serves as an example of straightforwardness and honesty in life and art. No one had a stronger influence on Adams – neither Paul Strand, nor Georgia 0’Kif, nor John Marin, nor all those who in the late 1920s in Taos helped him to see and find his creative way. Adams’ ‘Album Number One’ was released in 1948 with a dedication to Stiglitz, and the twelve works placed there are deliberately called ‘equivalents’, i.e. they use Stiglitz terminology. Adams wanted these works to be seen as ‘evidence of a spiritual relationship to the world around them’: art, Adams, and Stiglitz believe, should always bear witness to this relationship.

This conviction was and still is the cornerstone for Adams. His work cannot be divided into periods, although in recent years he has worked more with small machines and a single-stage ‘polaroid’ process. As an artist, Adams found his way early and has not left it since. On the day of his seventieth birthday, speaking at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the photographer once again confirmed his adherence to the principles put forward by Stiglitz, ignoring the past half table, which filled the art with nihilism, extreme experimentation, breaking with tradition, cynicism, digging into painful phenomena and the fashion of contemptuous despair: ‘Together with Alfred Stiglitz, I consider art to be a life-affirming force.

As a professional photographer, Adams takes a wide variety of shots inspired not by his own interest in objects, but by his customers’ interests. This does not embarrass him. Indeed, from time to time an accident, an essential factor in all art, especially the ‘art of finding objects’, opens up an opportunity for the photographer to go beyond a practical necessity and encounters a phenomenon that he is sincerely happy to display. For example, ‘Rails and Aircraft Traces’ was the result of an order from the firm American Trust to illustrate the history of California, and ‘Mount Williamson’ was the result of a self-order by Adams, who wanted to faithfully record the lives of U.S. citizens of Japanese descent interned at Camp Manzanar during the war with Japan. The case favors the one who waits for him. When Hamlet says: ‘Preparedness is everything’, you would think that he appeals to photographers.

Adams perceives everything visible with a deep feeling; he admires nature, its diversity, tenderness, and power, but there is no trace of its expansiveness: on the contrary, it is so restrained, even strict, that some consider it cold. Technically, he excels in the ability to convey what he sees and feels, and for half a century his work has been marked by such a bright personality that, rightly, does not require a signature.

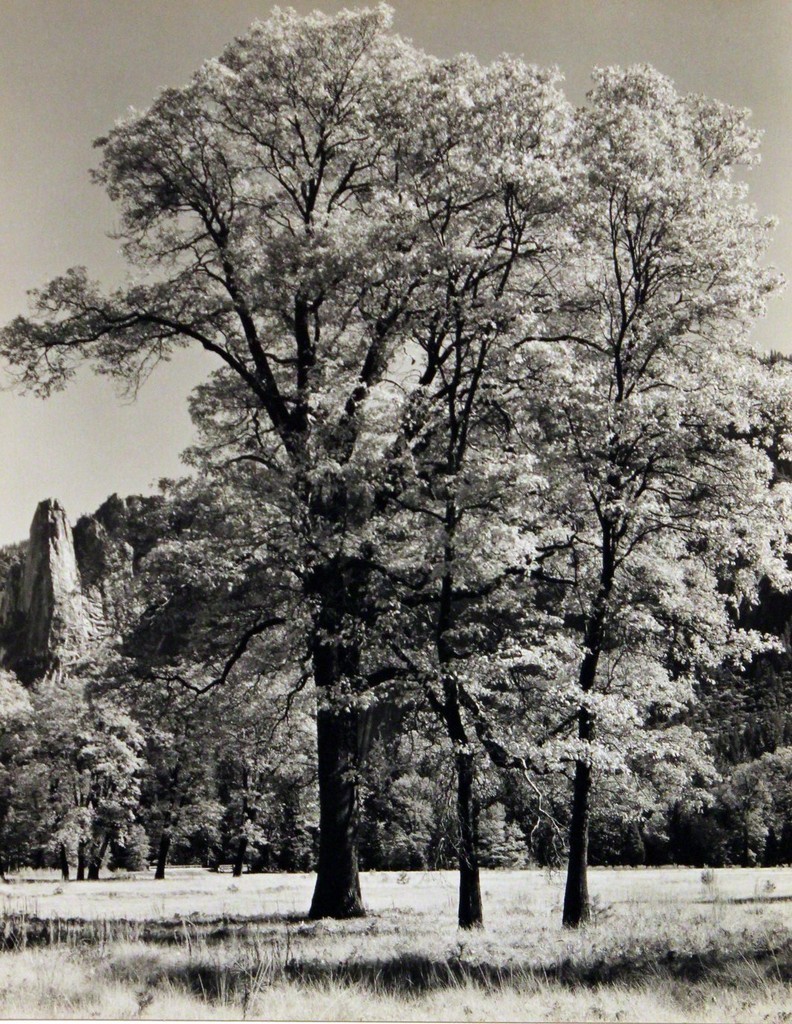

Adams’ signature

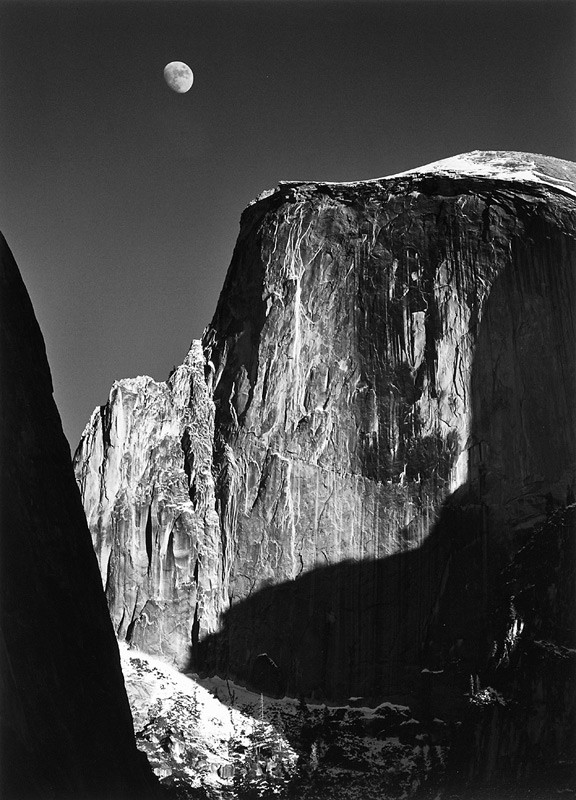

The ability of each successful work of Adams to do without a signature is due to the creative handwriting of Adams, but we do not have to deny that the theme plays a decisive role. Adams photographed a variety of places – Hawaii, New England, Southwestern states, California, Alaska, Canadian Rocky Mountains – and a variety of objects – faces, streets, houses, road signs, architectural details, factory equipment, tombstones, The texture of a charred tree or a tree that has been in the open air for years, the sea, the land, the bark that has left the tree, seaweeds, and ferns, in short, all kinds of forms that can be transformed by the artist’s and camera’s vision into a meaningful beauty. However, for most people, Ansel Adams is first and foremost the incomparable singer of nature, who photographed the mountains most often and from the mountains most often the Sierra Nevada, this ‘grandiose swing of the Earth’ with which he was captured as early as the age of fourteen.

But the spectators, who see in Adams only a romantic singer of nature, are unfair to Adams the artist. They overlook the vast and numerous areas of his art (when the exhibition ‘Expressive Light’ was held in 1964, reviewers agreed that no photographer in the world could match Adams in terms of quantity, quality, and variety of exhibits. Nature lovers in Adams honor a fighter for its protection, which is quite true but not always clearly see the line between a fighter and a singer or between themes and art. On the other hand, Adams’ reputation only as a landscape painter prompts some supporters of the photo report dedicated to the life of big cities, the ugliness of industrialization, and human misfortunes, to brush off Adams as an old man in love with the mountains, the author of excellent postcards, eternal romance, year after year photographing landscapes, which a hundred years before him photographed much better, as a photographer, if not completely indifferent to human suffering, then at least not able to depict them with the same impressive power as he depicts the cliffs, clouds and snow.

The ‘excellent postcards’ are not worthy of objection. Nor is it serious to accuse Adams of indifference to human suffering. But what is said about Adams’ portrait works, at least some of them, is not without reason.

‘Heads like rocks’

Adams’ most ardent admirers do not find strong arguments in favor of one kind of portrait, which Adams himself defends from principled positions. One critic noted that Adams ‘takes pictures of stones like human heads, and heads like stones. Adams does not attach much importance to ‘expression,’ in the sense that the word is usually understood. He does not belong to the ‘hidden camera’ school and does not want to catch faces that are distorted by grimaces. I photograph heads the way a sculpture would,” he wrote. – The head or figure represents some object. The contours, mass, texture, and general structure of the face and shapes show themselves with extreme intensity. Expressiveness – the variety of possible expressions – emerges by itself.

But some portraits of people in strict poses look stone, static, more like a statue of Roman heroes, like images of abstract qualities, not living people. Fortunately, many of the portraits in my warehouse seem to be ‘expressive’ in the common sense of the word, while some of the most casual ones, such as the portrait of Georgia 0’Keefe looking at her guide, in our opinion are completely at odds with Adams’ theoretical background. For most of us, his theory is too dry; no purely photographic advantages – intensity, lightness, purity of lines, texture, the richness of light-tonal solutions – will reward us for the vividness of his expression wiped from the face.

Although some portraits resonate with us like church bells, in the portrait genre others are at least as good as Adams, and therefore in the statement that ‘the nature of Adams photographs better than people’ – there is a share of truth. And he does not just photograph nature better than others, but better than everyone. Acknowledging this, both Adams’ rare enemies and his most enthusiastic admirers agree that he is above all a poet and a mystery man of nature. Many of Adams’ best images reflect the most grandiose, the most overwhelming, and the farthest from human nature.

Nature as a subject

The borders of nature are not landscape beauties. Beauty in the eyes of Adams is a negative concept, an invention of the tourism business, a large bait. Beauties are profitable, nature is awe-inspiring. The fewer traces of man in it, the better. When looking at nature, one shouldn’t look at one’s own person,” says Adams. Rarely, as far as I remember, a human figure is allowed into a landscape shot by Adams, even for ordinary considerations of scale. Scale, power, grandeur are portrayed by other, more difficult means. It’s as if a person with his or her petty self-awareness shrinks in front of the camera, and personal feelings serve only as a safety film on the lens, a means of increasing its visibility. The viewer’s response arises by itself in the same way as the expressiveness of portraits should appear: indeed, the principle that does not justify itself in a portrait photo, I think, turns out to be surprisingly fruitful in a landscape.

The borders of nature are not landscape beauties. Beauty in the eyes of Adams is a negative concept, an invention of the tourism business, a large bait. Beauties are profitable, nature is awe-inspiring. The fewer traces of man in it, the better. When looking at nature, one shouldn’t look at one’s own person,” says Adams. Rarely, as far as I remember, a human figure is allowed into a landscape shot by Adams, even for ordinary considerations of scale. Scale, power, grandeur are portrayed by other, more difficult means. It’s as if a person with his or her petty self-awareness shrinks in front of the camera, and personal feelings serve only as a safety film on the lens, a means of increasing its visibility. The viewer’s response arises by itself in the same way as the expressiveness of portraits should appear: indeed, the principle that does not justify itself in a portrait photo, I think, turns out to be surprisingly fruitful in a landscape.

Catch the moment

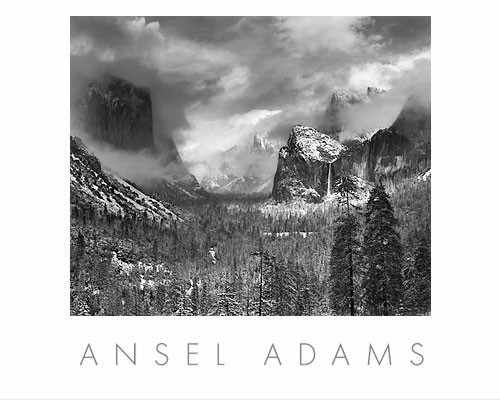

Let’s look at two famous works by Adams. One he did, returning one day at sunset in Santa Fe when he looked back at a village that had flashed outside the car window. The sun had already set, but the fading light was still hesitant on churches, mud houses, and burned-out white post crosses. In the east, the full moon had already risen above the snowy peaks of the Sangre de Cristo Ridge; between the moon and the mountains stretched pinnate cloud lit by the light of the sun that had hidden behind the horizon. The sky, the cloud, the mountains, the gentle slope washed away by the rains, the winding ravine, the village itself, the wormwood shrubs in the foreground – all this stretched from left to right in intermittent strips of light of varying intensity. And all this was dark in front of your eyes.

Adams assumed that he had no more than sixty seconds left to stop, jump out of the car, set the tripod, strengthen the camera, calculate shutter speed, adjust the lens and aperture, focus, and expose. When he took out the exposed film, the light was already dimmed. But Adams managed to immortalize ‘Moonrise. Hernandez, New Mexico,’ and the light will never fade over this photo. The photo is illuminated with a subdued, sunset clarity, it creates the ‘illusion of light’ for which many of Adams’ best works are famous. Only a desperate purist will protest against the fact that the cemetery crosses light up more ghostly white than they should. Here, the hand of the magician and the wizard of the darkroom intervened. After all, this is not the old Spanish village of Hernandez in New Mexico, filmed at moonrise in a cloudy haze, but the artist’s insight, the embodiment of an instant plan, realized in sixty seconds or even less. Sometimes,” says Adams, “I find myself in places where God only waits for the photographer.

Another laser beam slipped from the mountains in the east and got tangled in the tops of the poplars. The foothills remained in the shade, but the ridges were already blazing with cold fire. Almost at eye level, the sunny corner kept burning in the poplars’ branches. Adams again hid under the blanket and returned to the waiting state. The light finally broke past the left group of poplars and illuminated other trees and a strip of meadow along the stream on the right. There was a horse grazing. Light gathered in a puddle behind the horse, turning it into a black silhouette. Once again Adams hid under the blanket, waited for the right moment, and pressed the button. All this in any light could give a beautiful  picture, despite the inappropriate documentation of the letters LP. But Adams did not grasp the camera. He carefully studied the situation and imagined the possible final result. He figured out in his mind what possibilities would be created by this or that illumination. Then he came home, had dinner, and went to bed. The next morning, in the cold darkness before dawn, he went to the same place and waited. The transparent scattered light showed Adams a meadow with silhouettes of horses, a mottled hill, and a massive underside of the mountain. The photographer installed the device and dived under a black blanket. Then he dived out and plunged out waiting. Finally, over the White Mountains in the east, the edge of the sunlit up and lit up the highest peak of the Sierra Nevada like a laser beam. The pinkish light was flowing lower and lower, and finally, the whole mountain slope lit up. Then Adams dived under the blanket again, but soon he dived out again.

picture, despite the inappropriate documentation of the letters LP. But Adams did not grasp the camera. He carefully studied the situation and imagined the possible final result. He figured out in his mind what possibilities would be created by this or that illumination. Then he came home, had dinner, and went to bed. The next morning, in the cold darkness before dawn, he went to the same place and waited. The transparent scattered light showed Adams a meadow with silhouettes of horses, a mottled hill, and a massive underside of the mountain. The photographer installed the device and dived under a black blanket. Then he dived out and plunged out waiting. Finally, over the White Mountains in the east, the edge of the sunlit up and lit up the highest peak of the Sierra Nevada like a laser beam. The pinkish light was flowing lower and lower, and finally, the whole mountain slope lit up. Then Adams dived under the blanket again, but soon he dived out again.

The resulting photograph, known as ‘The Sunrise in Winter in the Sierra Nevada’ or ‘The View of Sierra Nevada from Lon Pine’, was not born from an instant. It was the result of a long wait for the desired moment, which Adams thought was bound to come. But just like ‘Moonrise, Hernandez’, this photo is a miracle. The sky beyond the mountains is slightly dimmed and emphasizes the smooth movement of the morning clouds. The white silence of the majestic Sierra Nevada, fenced in by rifts and gorges, flutters like a banner in the wind. Down below, as if supporting the mountains, an almost black hill is illuminated just enough to reveal the complex structure of its surface – rocks and shrubs. Now there is no mark on it. The scar, which has an unimaginable landscape, has been erased from the negative. A hand of dawn grows visibly below the dark hill, reaching for the meadow by the creek. It carries with it a renewal, rebirth, support. Right before our eyes, it seems to lie on the dark silhouette of the horse and warm the animal, as every dawn should warm all life on earth.

These few belong to Ansel Adams, and Conrad is remembered again with his definition of the artist’s purpose:

‘To hold for one moment, for one breath, the light hands of earthly laborers, to make people, fascinated by the spectacle of a distant goal, look back at the forms and colors surrounding them, at sunlight and shadows, to make them slow down, look around, smile, sigh – this is the goal of art, difficult, fleeting, achievable only for a few chosen ones.