On Thursday, Bob Dylan — former folksinger and legendary rock artist, boomer icon and generational outlaw/fugitive, historic figure and fabulous provocateur, you know, that Bob Dylan — was awarded a Nobel Prize in Literature “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition,” which raises the question: did he deserve it? The debate isn’t between rock people and lit people, as one might guess; it’s about the value of blurring the categories. Lit people regard the man as a vulgar interloper stealing good press from whatever novelist was next on the list, just like he stole lyrics from Henry Timrod, shame, shame. Rock people moan that songwriting isn’t literature, music is the man’s medium, Leonard Cohen’s lyrics read better on the page anyway so why don’t you take him and leave Dylan to those of us who can appreciate him, so there. Both agree that rock is rock, literature is literature, never the twain shall meet, let’s keep the categories distinct please. Those who approve of category-fucking stand in opposition.

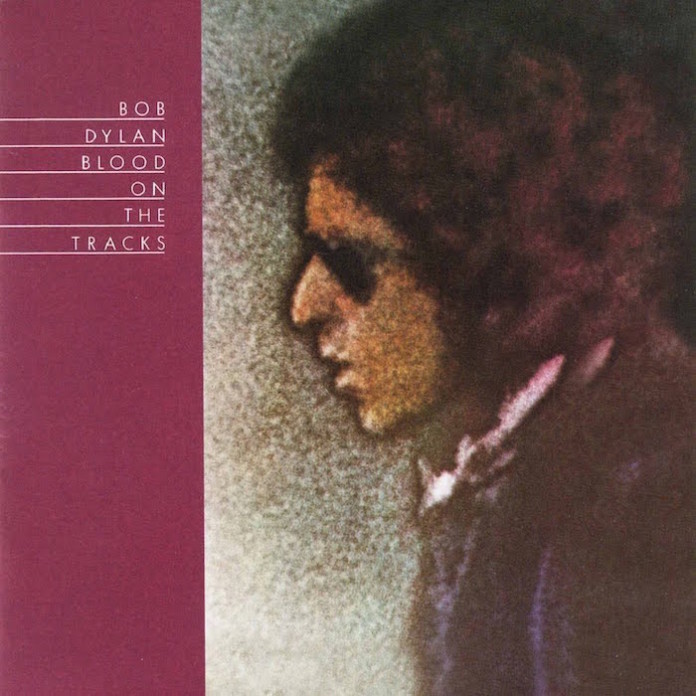

Dylan belongs to the latter group. Throughout the history of modern popular music very few and perhaps none have fucked categories with such relish. Dylan who played the folkie and the poet and the prophet and the rocker and the actor and the dilettante, Dylan whose whole career was based on dodging audience expectations, Dylan who invented reinvention a decade before Bowie got the credit — listen only to his ‘62-’69 albums and you’ll still hear at least four or five distinct performance personas, each with its own band sound and corresponding constructed vocal style. Maybe the literary world won’t take him, but he hardly fits into the rock pantheon either, no matter how many awards he’s won or how many five-star Rolling Stonereviews his albums earn. Like other performers who shift roles at will (Bowie and Prince come to mind, just for starters) only to a more extreme degree, he’ll never be truly at home in the rock canon, because he’s just too singular a figure. To quote a 1975 Robert Christgau review from The Village Voice, “there are times when I crave a specific Dylan record with a fervor of the will no other artist can arouse in me, and I value him immensely for that, but only rarely can he just be part of a stack.” Christgau was writing about Blood on the Tracks (1975), Dylan’s epic song cycle about a lost affair. He suggested that the aspiration to “just be part of a stack” was one of the album’s flaws; play it up against, say, Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run (1975), however, and you’ll hear the difference between someone who believes in rock & roll and a dangerous outsider who picked music as his medium so he could play mind games with the mass audience. Perhaps keepers of the rock canon adore him for this very reason. In a way, he couldn’t be so central if he didn’t stand outside the tradition.

That’s also why he gets respect from highbrows with no use for rock & roll, many of whom say screw the music, just read him as a poet, he’s really a literary figure. Problem is, he’s a lousy poet by highbrow standards, Christopher Ricks to the contrary. You have your favorite exceptions and I have mine, but few Dylan lyrics work on the page without benefit of music. They come alive as he sings them, as he imbues them with character and feeling, inserts pauses, nuances and the like, mangles and mispronounces words, generally adds shades of meaning lost in the transcription from song to written language, and, crucially, contextualizes them in the frame of a persona constructed through performance. That’s not to deny his lyrics sound poetic at times, especially in the mid-’60s when his dense, inventive, towering walls and/or streams of associative imagery peaked in terms of density as well as invention, and he played the poetic genius more consciously than most attracted to such a pose. But it’s still a pose. Whether or not he raised popular music to the level of literature — a meaningless claim lazy boomers have been pushing on the younger generation for years — he certainly assumed the role of the Romantic author-genius in a popular context and made the resulting dialectic thrilling as hell. I don’t expect his rock acolytes or his poetry acolytes for that matter to grasp the distinction, but his is not a literary achievement as those with cultural power define literature.

In short, the inappropriate category error of Dylan’s Nobel Prize suits him exactly. How perfect that this perpetual troublemaker should earn the highest honor in a field he works in only tangentially, because it means he’s broken another barrier. If his award leads people to rethink the category of literature, good — it’s about time, and ditto for the category of popular music. Take a step back for a moment, forget Dylan specifically, and jump for joy — a popular musician, any popular musician, won a Nobel Prize. Dylan, with twelve Grammys and eleven platinum albums to his name, didn’t need the honor. It was the popular music tradition that won big. Celebrate Dylan’s award as a key milestone in pop music’s long march toward the respectable highbrow credentials it has still failed to earn. Even if you prefer your culture vulgar, unsullied by stuffy reverence or institutional support, consider the practical consequences that at the very least lurk in potentia: more college courses and graduate studies on pop music, more funding for the 99% of musicians occupying the sales chart’s long tail. Institutional support matters sometimes. I’m grateful the Nobel Committee extended it to the world’s premier singer-songwriter.

How can you resist the man? He enters realms far outside the merely literary. Check out this poetic gem, from 1990’s Under the Red Sky:

Wiggle til you’re high

Wiggle til you’re higher

Wiggle til you vomit fire

Wiggle til it whispers

Wiggle til it hums

Wiggle til it answers

Wiggle til it comes

Wiggle wiggle wiggle like satin and silk

Wiggle wiggle wiggle like a pail of milk

Wiggle wiggle wiggle all rattle and shake

Wiggle like a big fat snake

I don’t care about categories like literature and great art. I’m no monkey but I know what I like, and I like Bob Dylan. He can’t help it if he’s lucky. That brand new prize balances on his head just like a mattress balances on a bottle of wine.