The American painter John Singer Sargent is known for his lavish portraits of the great and glamorous of his day, from the leading actress Ellen Terry to the politician, art collector and Mayfair dandy, Philip Sassoon. What is less known is the extent to which Sargent personally styled his subjects. A new show opening this month at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston reveals that the artist not only had an eye for fashionable sitters, but for fashion itself.

Boasting a number of sensational loans—including Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau) (1883-84), from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art—the exhibition Fashioned by Sargent will prove its point by pairing several portraits with the actual clothes shown in the paintings, demonstrating how Sargent manipulated clothing to achieve his desired ends.

Among the 73 paintings and objects on view are the 1889 portrait Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, along with her moss-green gown, embroidered with real iridescent beetle-wing cases, which the actress wore in a celebrated London production of Macbeth. In the painting, Sargent shows Terry crowning herself, her flowing Gothic get-up looking like a whole stage set rather than a mere costume.

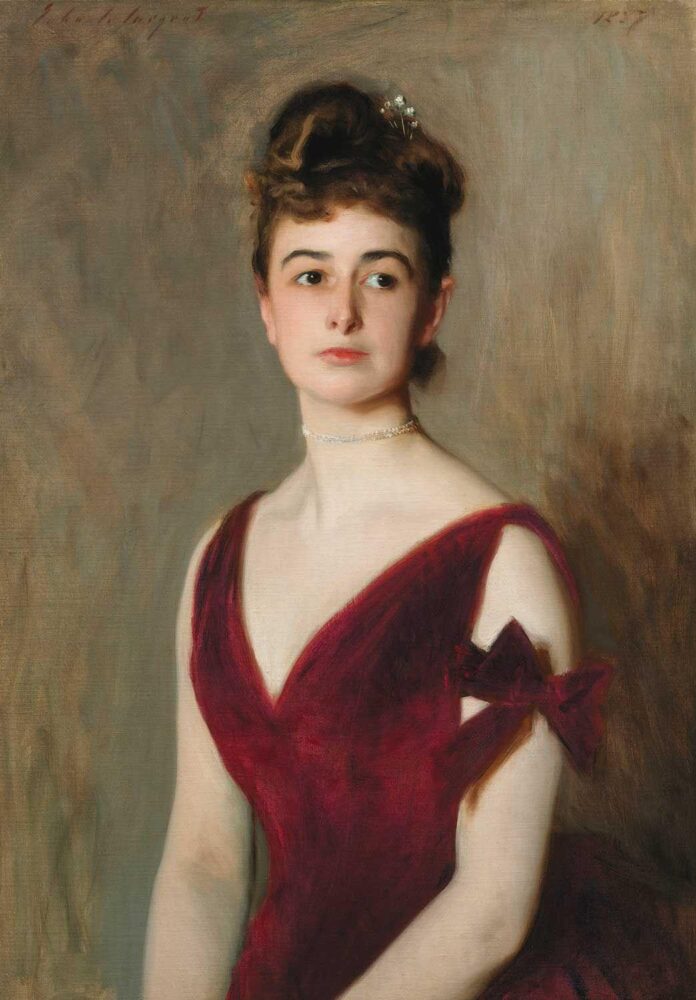

The elegant silk-velvet dress Louise Pomeroy wore for the Sargent portrait

Photo: © MFA Boston

A lifelong expatriate, Sargent (1856-1925) was born in Florence to American parents. His Eurocentric approach to portraiture was rooted in his Parisian training and a deep affinity with the Dutch artist Frans Hals and the Spanish painter Diego Velázquez. But he made crucial trips back across the Atlantic, and the show will recall his eye for home-grown American style in Mrs Charles E. Inches (Louise Pomeroy), an 1887 portrait of the Boston socialite. Her red silk-velvet evening dress, which is in the MFA’s collection, accompanies the portrait.

Unlike the Old Masters that inspired him, says the exhibition curator Erica Hirshler, Sargent could take advantage of the late 19th-century’s “brilliant new chemical pigments,” which gave his paintings their ravishing palette. Hirshler cites Sargent’s 1907 portrait of Philip Sassoon’s mother, Lady Sassoon, shown in a black silk taffeta opera gown lined with bright pink silk satin. “The cloak hangs down straight when you wear it”, concealing the lining, she says. But Sargent “twisted and pinned,” so that the final painting is marked by a fine, long, neon-like plumage of pink.

Sargent’s painting Lady Sassoon (1907) and her cloak made from silk taffeta and satin © Houghton Hall; Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Arranged thematically, Hirshler saves Madame X, Sargent’s celebrated early portrait of an American-born Parisian socialite in a low-cut black dress, for a middle section of theshow dedicated to fashion and power. Sargent let the simplicity of the black gown’s figure-hugging silhouette speak for itself by hiding a then fashionable bustle, transforming its wearer into what Hirshler calls “a work of classical sculpture”.

Women’s clothes of the period may now seem more dramatic than mens’, but Sargent could make the most of his male subjects, says the curator. In another key loan, the show has managed to get Dr Pozzi at Home (1881) from the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Pozzi was a Parisian gynaecologist, who Sargent— now viewed as having been gay—seems to have had a crush on (“exactly Sargent’s type”, Hirshler says). He dressed the dashing doctor in a crimson-red, all-too-private robe de chamber, culminating in what the Sargent biographer Paul Fisher regards as one of the artist’s most daring works.

Sargent’s Dr. Pozzi at Home (1881) Armand Hammer Foundation. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Sargent himself was anything but a dandy (“He dressed like a banker”, Hirshler says). But he brought a dandyish cast to a 1917 portrait of John D. Rockefeller, when the founder of the Standard Oil Company was in his late 70s. The otherwise stern-faced sitter is shown in repose, his white-clothed legs casually crossed in pleats of ivory, eggshell and pale grey. “Sargent loved painting white on white,” Hirshler says.

A London version of the show, at Tate Britain next year, will include another white-on-white tour de force, Duchess of Portland (1902), in which the white folds of the duchess’s gown play off the white Ionic columns of a manor-house chimney piece.

• Fashioned by Sargent, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 8 October-15 January 2024; Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain, London, 22 February-7 July 2024