When filmmaker Sarah Vos began developing her documentary on Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, she had only intended to chronicle its early days under the stewardship of newly appointed director Rein Wolfs. But over the next three years, during which Vos gained access to every aspect of the museum’s operations, her cameras caught something far richer: the Stedelijk’s monumental and uneasy effort to diversify its staff and collection.

The resulting film, wonderfully titled White Balls on Walls (after a placard at a Guerrilla Girls action), is that rare, and incisive, document of a centuries-old institution struggling and striving to meet a more inclusive era.

As we’re told at the top of the documentary, male artists represented 96 percent of the Stedelijk’s collection, just as its workplace was overwhelmingly white. To begin chipping away at this stark imbalance, the museum allocated 50 percent of its acquisition budget towards works by artists of color and began diversifying its hiring practices.

Those are initiatives you might hear about in a glossy press announcement. The reality, as we’re privy to, is the stuff of interminable Zoom meetings and discussions as the Stedelijk staff hammer out—and agonize over—the intricacies of inclusivity. What does the term “of color” mean? Should the word “prostitute” in an artwork’s title be replaced with “sex worker”? Will hanging works by Black artists in a single room be interpreted as creating an “African zone”? What about the problem of Picasso?

That a museum, much less one as storied and esteemed as the Stedelijk, should allow a film crew to document its frank conversations and navigations around diversity is striking. But no, Wolfs told Artnet News, he wouldn’t call it courageous.

“I think giving this access opens the possibility to make something of an exemplary situation, where the successes but also the failures of this whole process are being shown,” he said. “At the end, it’s a very authentic document; it becomes very human. And I think authenticity is the means from which you can learn.”

Still from. Courtesy Icarus Films.

Or as Charl Landvruegd, the museum’s newly hired head of research and curatorial practice, put it in the film: “It is this pain the white community now experiences that is part of the process we should expose.”

There are many more factors at play for the Stedelijk too. At the forefront, its impetus to embrace diversity followed a directive from city hall, on which the museum’s funding depends, creating a sense of urgency as much as an air of opportunism that hangs over the proceedings.

There’s also the Stededlijk’s standing as the keeper of Dutch Modern and contemporary art history. What would it mean for the museum to rewrite the art canon to correct historical exclusions? For starters, Wolfs directs the removal of the towering sign on the museum’s facade that once read, “Meet the icons of Modern art”—a “symbolic act” for the new director.

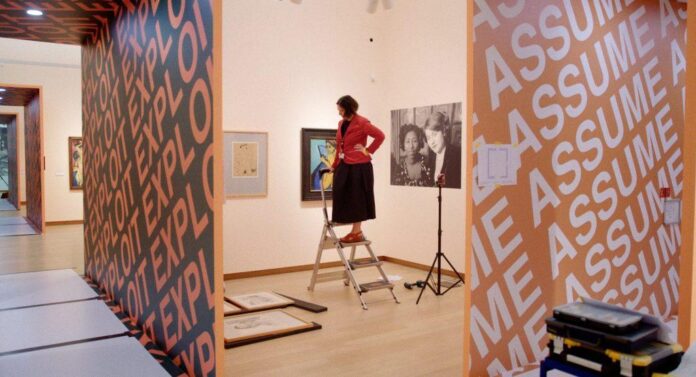

Curator Beatrice von Bormann in the Stedelijk’s storage. Still from . Courtesy Icarus Films.

Heavier lifting is done in the bowels of the museum. Curator Beatrice von Bormann dives into the Stedelijk’s storage to resurface works by women artists including Frieda Hunziker and Else Berg (some of which weren’t even listed in the museum’s database) for a rehang. Meanwhile, Landvruegd and members of the research team engage in a tense yet candid dialogue around the Western art canon. “You have to acknowledge that this is history,” argued researcher Frank van Lemoen. “One wonders whether inclusiveness isn’t some kind of utopia.”

“The whole diversity process,” Wolfs reflected to Artnet News with some understatement, “is a process in which there are so many pitfalls, internally but also externally.”

Indeed, those tensions aren’t just present within the Stedelijk (right down to a security guard who is flummoxed by the new gender-neutral bathrooms), but radiates outward to its public. Towards the end of the film, the museum opens its “Kirchner and Nolde” exhibition that pointedly confronts the role of colonialism in the titular Expressionists’ practices—to scathing criticism from the press and visitors for its “exaggerated political correctness.”

Such feedback might resonate with museums globally as they embark on their own DEI efforts, and more so at a moment when the arts have become increasingly politicized and audiences polarized (looking at you, Florida). For what it’s worth, according to Wolfs, the label of “woke museum” has followed the Stedelijk since filming wrapped.

Stedelijk Museum director Rein Wolfs. Still from . Courtesy Icarus Films.

White Balls on Walls, with its unfussy editing that makes for uncomfortably extended scenes, essentially contends that any push toward inclusivity remains a demanding and continued process. Even Wolfs himself recognizes that change for the Stedelijk, an institution with more than 100,000 works in its collection, will probably take decades.

“We will never achieve the perfect balance, as there will always be individuals and groups with their unique stories that must be included to create a more accurate reflection of our society,” he admitted, and yet: “We have made huge steps in terms of being aware of our history and what we could do better in the future. Like most museums, we have a history of, let’s call it, systemic exclusion. We are aware now so we can make some changes.”

And this progress isn’t just necessary, but inevitable as well.

As Wolfs, in the film, appropriately asked: “Should we be politically incorrect? That can’t be an option, right? That can’t be an option in this world, can it?”