A vintage photo album, taken by Ed van der Elsken, was sold for $ 21,250 at auction in New York. That set a new record for a Dutch photographer and filmmaker.

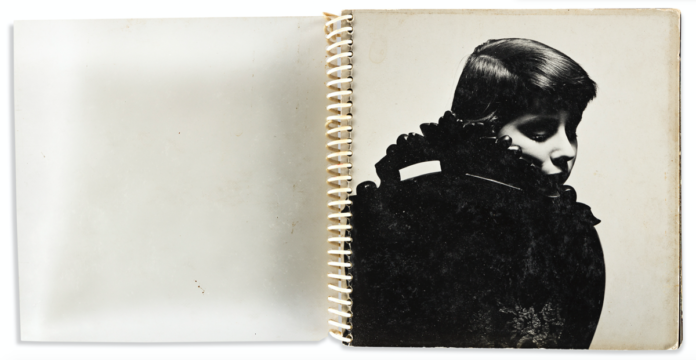

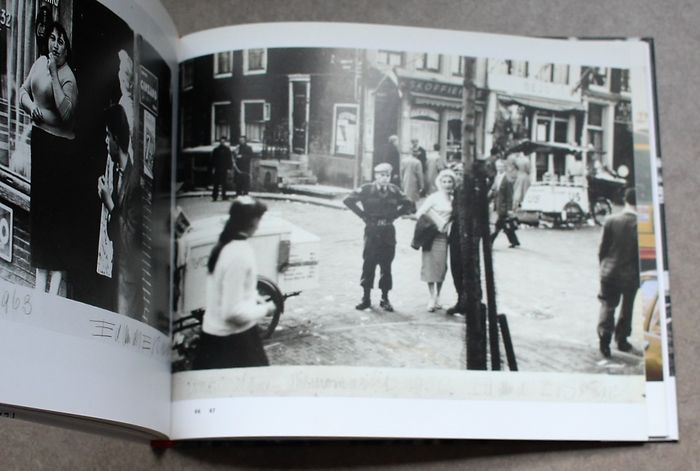

Made in 1951, this untitled photo album includes 27 black and white photographs of street scenes in Paris, as well as portraits of Dutch photographers Emmy Andries and Ata Kando (who was married to Elsken).

Five applicants competed for the work during a photo auction on March 11 at Swann Galleries in New York, where it was valued at $ 10-15 thousand. Curator Hans Roosebum of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam acquired it on behalf of the museum.

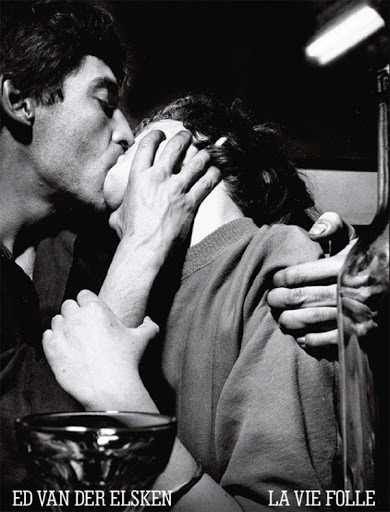

The work was sold on the market for the first time. For seven decades, it has been in the hands of the Elsken family. The result surpassed the last record for Elsken’s photo album at auction, set by his 1962 book of 99 photographs entitled The Crazy World. This work was sold in Haarlem, The Netherlands in November 2013 for $ 16,300.

The street photographer Elsken, who worked from the 1940s to the 1970s, is known for his black and white photographs of urban life throughout Europe. In 1950 he began living in Paris. There, he worked for the respected Magnum Photos agency, printing photographs for Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa.

In 1952, Edward Steichen included it in the MoMA exhibition, and in 1956 he published his first book of Parisian photographs entitled Love on the Left Bank (1956).

In June 2020, the Rijksmuseum and the Photomuseum of the Netherlands announced plans for the two museums to jointly acquire the artist’s estate, consisting of more than 10,000 photographs, some of which were donated to Anneke Hillhurst, the artist’s widow.

Deborah Rogal, Swann’s head of photography, said in a sales statement that the work could add to our understanding of the photographer, who is now attracting new and deserved attention from collectors and organizations.

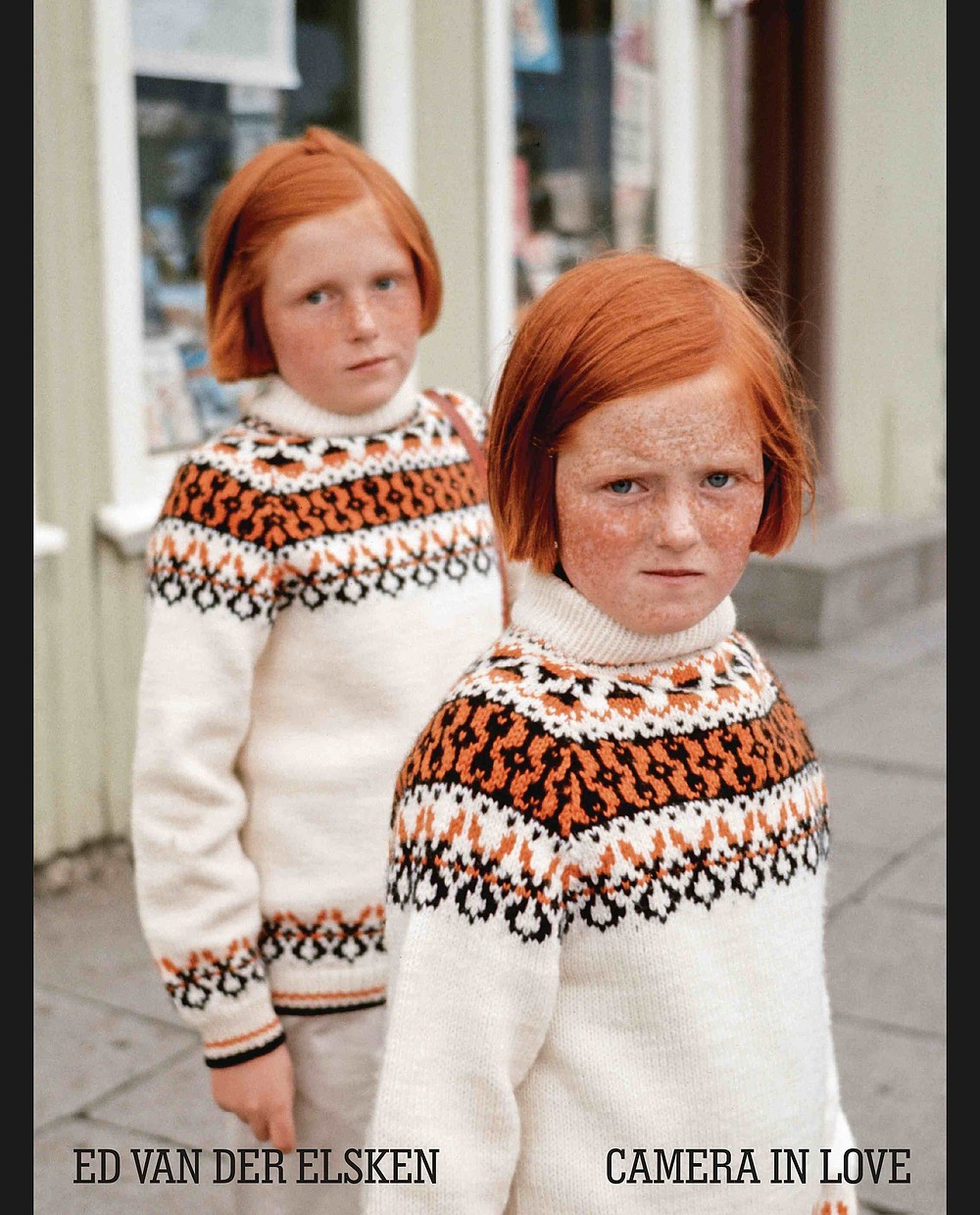

Ed van der Elsken. A journey through the street photographer`s life and works

Street photographer Ed van der Elsken (1925–1990) is an outstanding figure in 20th-century Dutch documentary and photography. As a photographer, he preferred the outdoors, and in cities such as Paris, Amsterdam, Hong Kong, or Tokyo, he loved to hunt for objects.

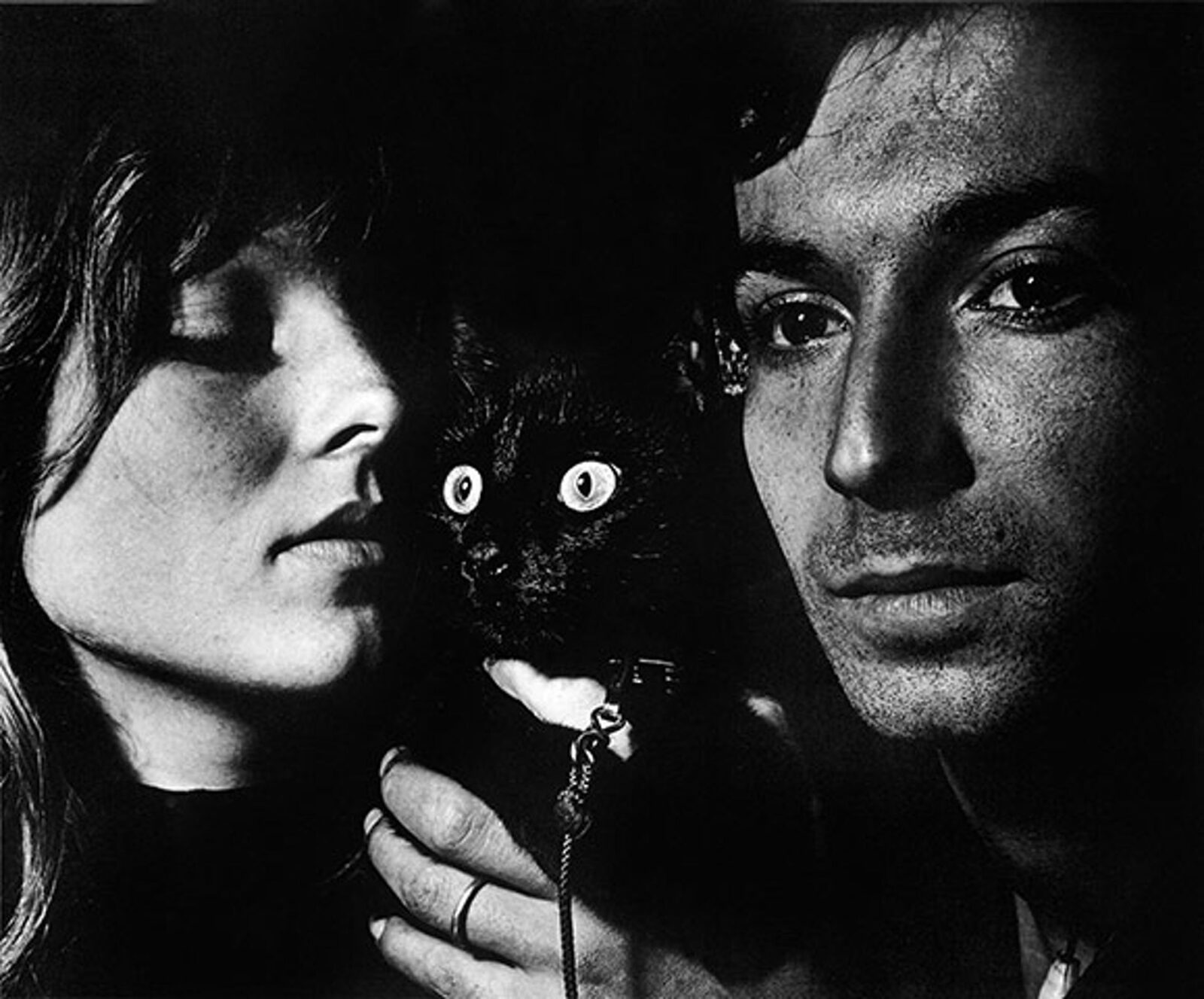

He was often called a street photographer of marginal figures, he really strove for aesthetic form, visual authenticity devoid of subterfuge, the beauty that was sometimes overtly sensual and sometimes even erotic. Van der Elsken published approximately twenty books and produced a large number of films.

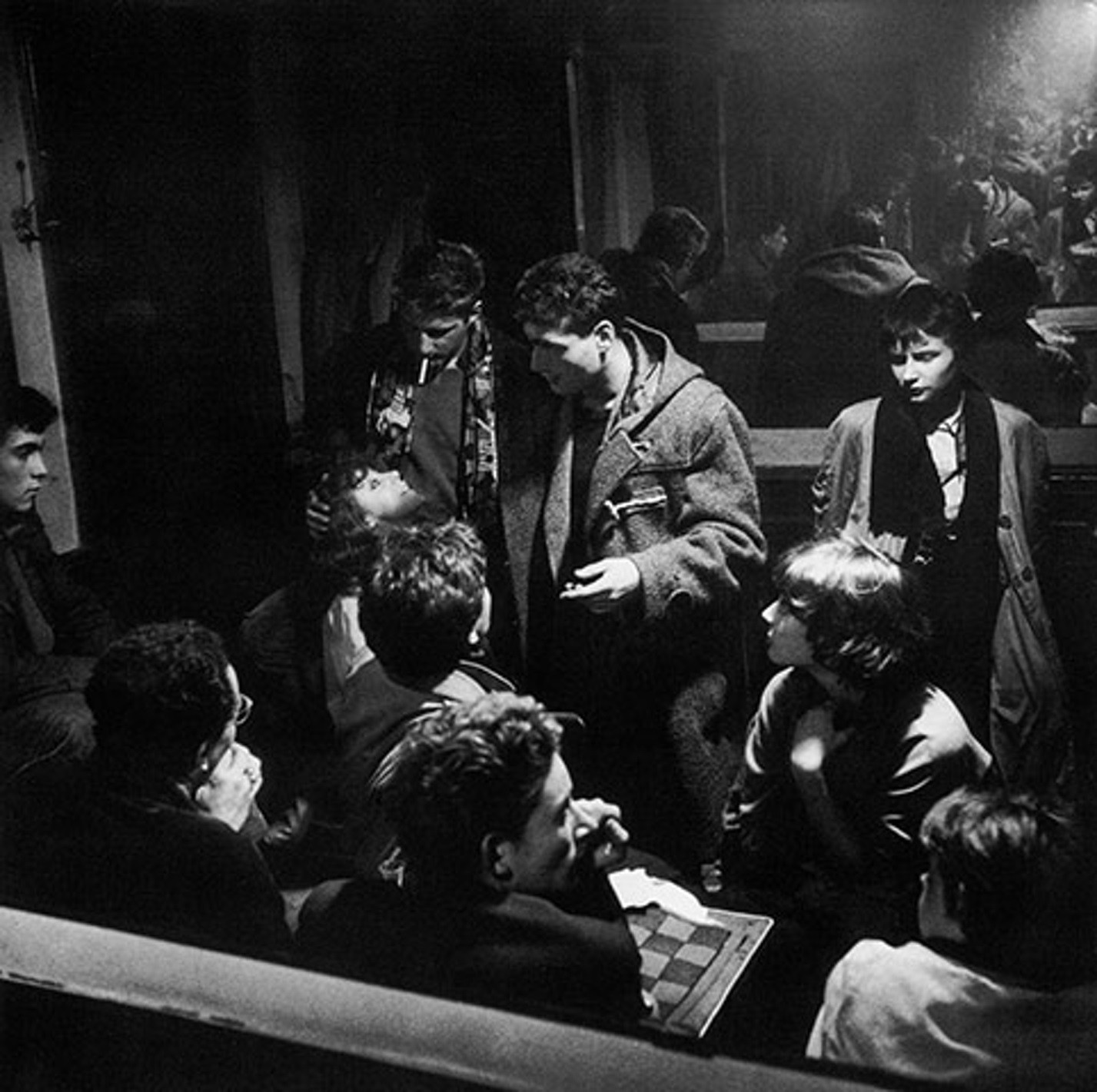

His first book was called Love on the Left Bank. It was published in 1956. Love on the Left Bank is a semi-fictitious tale of disaffected young people living in Paris after World War II. It was followed by a number of photo documentaries from his travels: Bagara (1958) featuring photographs from his trip to Equatorial Africa, and Sweet Life (1966), from his round-the-world journey in 1959-1960.

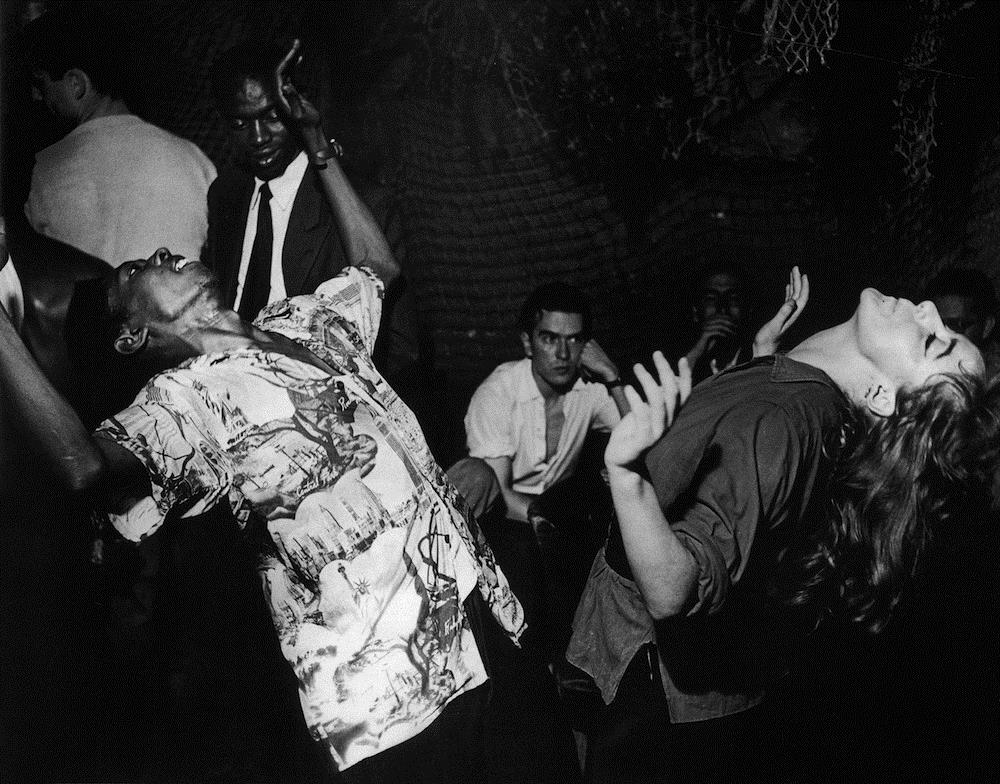

Jazz (1958) is also worth mentioning. The book is a bright ode to the explosion of jazz music on the Amsterdam stage.

In the 1980s, he published photo books about Paris and Amsterdam, as well as Discovery of Japan, based on his many trips to this country.

In 1982, Van der Elsken completed the one-hour film “Een fotograaf filmt Amsterdam”. In English, it was given the name “My Amsterdam”, but the original Dutch is better because in many ways it is a photographer’s film. Not because it contains still images, but because it is a kind of homage to the city that he has photographed so often in the past.

Structurally, it is unusually rigorous work, alternating between long, continuous footage from a car racing through an empty city center and spontaneous footage of people Van der Elsken spots on the street. As usual, he is drawn to vibrant extremes: hippies, hell angels, drug dealers, eccentric outfits, and women in miniskirts. As you watch, you may wonder how you or Van der Elsken could have photographed these scenes, as if a still frame from a movie could be the equivalent of a photograph taken in the street itself.

Van der Elsken never allowed his images to stand alone in their silence. They have always been modified and mediated by sounds, voices, and signatures or experimental formats of his books and exhibitions.

The street photographer Van der Elsken has always been an outsider in a way. A fierce anti-capitalist, just as much an anti-communist, he was never an ideologist. His signature images of rebellious youth – whether Dutch rockers or Japanese yakuza (gangsters) – are driven by a sense of personal identity and celebration rather than a social outcry.

He rarely pretends to be neutral or detached: he is always emotionally and dramatically present in his photographs. Sometimes gentle and romantic, sometimes harsh, vulgar, even obscene, van der Elsken is invariably uncompromising and straightforward in his approach. And especially Bai (1990), his last farewell film, which chronicles his slow decay from prostate cancer. He died on 28 December 1990.

When Van der Elsken died at the age of 60, one of his projects that never came to fruition was an extremely ambitious mixed media production. Tokyo Symphony was supposed to be a programmed multi-screen slide projection accompanied by sound.

He left 1,600 color slides for the project, as well as five reels of audio recordings. A celebration of a country and culture that has engulfed him from the very beginning of his life, Tokyo Symphony has all the key characteristics of his work – switching between reporting and subjective poetry, an abundant mixture of influences, a love of tradition and modern life, a piece with consonance and dissonance, and form, which is difficult to classify as a work of film, photography or writing.

Outside of his home country, however, Van der Elsken was not so well known, although in recent years he became recognized as a pioneer of some kind: an unpredictable free spirit, whose images seemed to arise directly from his own idiosyncrasies.

His photographs fall outside the classification, his books challenge genres, his exhibitions throw curatorial rules out the window, and the extraordinary range of his films never ceases to amaze.

The obvious limitlessness of Van der Elsken’s creativity and his personality today attracts the attention of the whole world.

One of the main reasons Van der Elsken eluded attention was that he was not overly interested in the sheer art of “fine art” photography or the creation of individual iconic images for contemplation. His films were eminently informal and often technically messy, giving the disarming impression that they were unmediated fragments of a wayward and itinerant life. His aesthetics seemed to be based on improvisation, spontaneity, and chance.

Today, of course, contemporary art is deeply interested in informal and hybrid practices that reflect how everyday life today is so precarious and fragmented. Perhaps, it’s time for the street photographer Van der Elsken.